They had decided to re-trace their steps from yesterday. Okay, we’d just follow them. I mean, how hard could it be – they’d come up once already by that route, right? So, the nightmare began. I remember my huge pack, heavier than anything I’d ever carried before (everything in it was sopping wet), throwing me off balance as we side-hilled across a steep snow slope. Before we could start to descend, we had to cross the Robson cirque above the icefall, then climb uphill to reach the start of the Razorback

Their steps went over to, and on top of, the Razorback, via a narrow ice arête. Very exposed, windy, and, of course, zero visibility. Well, it went from bad to worse. The route down was a succession of increasingly-difficult cliffs of rotten rock, with a degree of difficulty to Class 5.8. Here are some photos which will show you what we had to deal with. This first one was taken when we flew in by helicopter, and it shows the upper part of the Razorback. It is all the rock you see in the near lower part of the photo. The Kain Face is seen end-on on the far left.

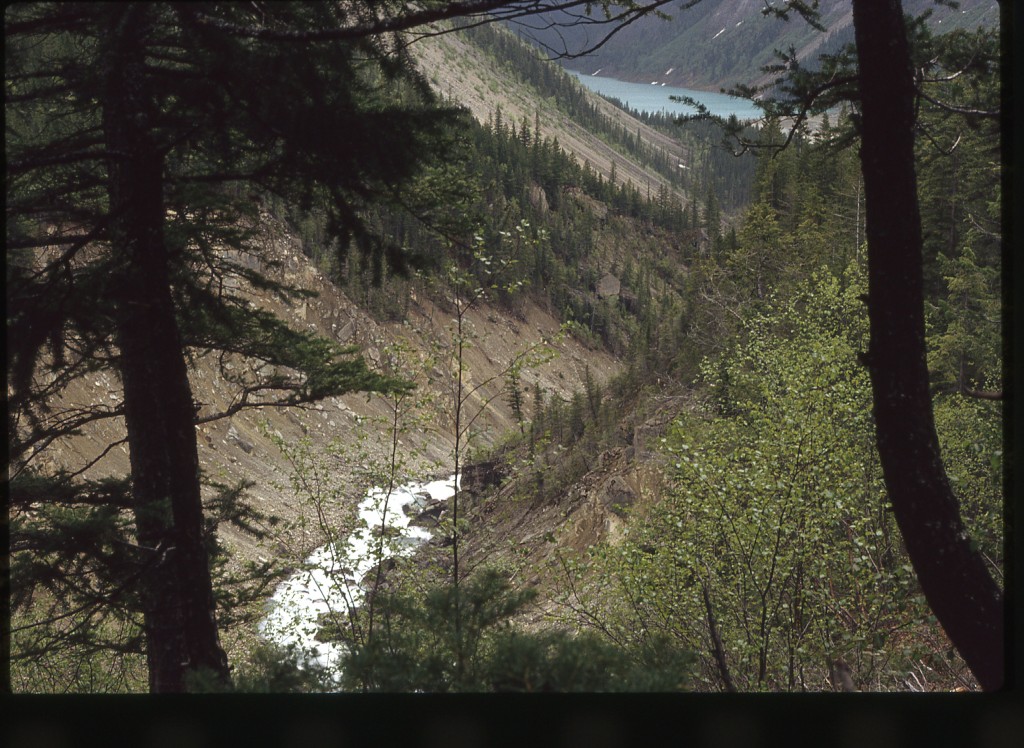

And here’s another view, as seen from 8,500′ elevation down on the Robson glacier the day we flew in. The Razorback is the rock and ice ridge on the skyline, taking up the left half of the photo. It goes up to the huge rock face in the middle of the upper part of the photo on the skyline. To start our descent, we had to climb to the left, up the ice, just below the rock face to get on to the top of the Razorback.

Here’s an idea of the worst one, which took hours to negotiate: the three of us were huddled together, with barely room to stand, in a complete white-out, wet snow being blown uphill by powerful winds blasting up from the south side. We had to lower our 90-pound packs down, and fix a route that we could safely down-climb with jumars. We were soaked to the skin, and becoming very cold.

There were 12 cliffs, or really steep parts, the worst (described above) about 150 vertical feet. There were times when we had better visibility, only to be replaced moments later by white-out conditions. I remember glancing at my watch at 2:00 pm. Before we knew it, it was 8:00 pm and getting dark quickly in the clouds. A choice needed to be made – either do an emergency bivouac where we were, or call for a lead in. We hollered down to Richard and Dave – they were in their tent and could hear us, but not see us at all. In fact, they had been hearing us all day. Our problem at the moment was that we couldn’t see jack. They asked us if we wanted them to come up to us. We said yes, and so they did – they could see the flickering of our headlamps. They met us on the ridge – it turned out that we hadn’t gone quite far enough over towards the col with Mt. Resplendent. The guys guided us down through the soft snow to the spot where they had pitched their tent. What a relief to be done. All that ordeal in order to end up about one mile, as the crow flies, from our camp on the Dome. It had taken us 15 hours to drop a little over 1,000 feet. Scott had lost one of his three tent poles during the descent of the Razorback, so the tent went up only poorly. By the time we crawled into our sleeping bags, soaked to the arse, it was almost 1:00 am. I was completely knackered. I know that I really slowed Scott and Brian down on the descent, and felt really out of my element. Much of the time I was really concerned, but Scott and Brian performed miracles with their rope-work.

Day 11. When we awoke, it was snowing. There had been some discussion earlier about trying for Resplendent, but we couldn’t even see the thing so we said fuggedaboutit.

We broke camp and started down with very heavy packs – it seemed like everything we owned was saturated. The task at hand was to get down through the Robson glacier, and so down, down we went.

There were different levels of icefall, but after a while the going became flatter and easier.

Finally, we unroped and took off our crampons. In the rain, we reached and rounded the Extinguisher Tower. Just below it, we stopped and ate lunch on a smooth granite slab.

Richard and Dave had gone ahead – they were so much faster, it made no sense for them to hang around waiting for us.

The miles passed, and, by the time we had dropped 2,000 vertical feet on the glacier, the sun was trying to peek through the clouds.

Crossing a creek, we got hung up, so we traversed the irregular side of the glacier. From time to time, we saw amazing things like this – a roaring creek rushing headlong into a huge hole in the ice.

It was better than staying on the lateral moraine, so we followed it all the way to the toe. There, the glacier calved icebergs into a lake which was the start of the Robson River. We were able to pick up the trail from Snowbird Pass (at that point we were only a quarter of a mile from the Alberta border), and followed it all the way to the Berg Lake chalet.

It was jammed full of tourists, mostly foreigners. I remember we were quite a sensation, and were peppered with questions for a long time. They were amazed to learn where we had spent the last 11 days, even more so when we pointed up the mountain to show them. All our gear was still sopping wet, so we hung it all up on makeshift clotheslines all over the large open single room that was the chalet. The wood-burning stove produced a nice heat, and our stuff was steaming in no time. This next photo shows the upper 8,000 vertical feet of the mountain as seen from near the chalet.

We ate and drank to repletion, sitting around until all hours talking with our new-found friends. There was a rule clearly posted in the chalet, stating that it was not allowed to sleep inside. Of course, we did anyway, and were subjected to a night of rodentia running around the place and over us.

Day 12. People started coming inside early, so we didn’t get much sleep. Our feet were so sore from yesterday’s march. Overnight, our gear had dried and was much lighter, so our packs were easier to carry. Naturally, a drizzle was falling as we set off! There were twelve more miles to cover, and each one became exponentially more painful. We stopped to soak our feet in the icy river a few times to get some relief, but that was only temporary at best. Even the spectacular Emperor Falls almost didn’t merit stopping for a photo, given the mood I was in.

It turned into an excruciatingly painful grind, even the last few miles around Kinney Lake.

At long last, we reached the parking lot at the trailhead. I was so disgusted with my old first-generation goretex suit that I tossed it into a trash can. Same with my supergaiters. My boots, a pair of Peutereys made by Galibier, had become my worst enemy. They were a classic leather boot, steel shank, heavy as hell and awfully stiff to walk in. Fine for crampons, but they had turned my feet into hamburger on the walk out. Into the trash can they went.

The problem was that Scott’s car was still miles away, so he bummed a ride back to Yellowhead Helicopters where it had been parked for the better part of two weeks. After some time, he returned. The three of us, as well as Dave and Richard, all piled in along with our mountain of gear. In no time at all, we were back in Valemount. Turns out I could get a refund on the return portion of my train ticket, so it was bus tickets for Brian, me, Dave and Richard. I can’t remember what time we boarded the Greyhound, but the four of us sat close together and talked climbing into the wee hours. Our excited chatter must have pissed off some of the other passengers, because the driver had to get on the PA system more than once to tell us to shut the hell up, or else. Sheesh, who wouldn’t want to hear us tell climbing yarns all night long rather than sleep? Some people have no class.

I disembarked at the town of Abbotsford at 4:00 am, caught a few winks on a hard bus-station bench, then found a diner for a breakfast of pancakes. Not wanting to wake anybody up too early, I waited until later to make a call. Lee, my brother-in-law, drove over from the next town to pick me up and take me back to his place. So my story ends. One post-script to add, though. I never saw Scott again. A month later, Brian phoned me. Always a man of few words, he informed me that Scott was dead. He had come back to BC to do a solo attempt of the very challenging ice climb known as the northwest arête on Wedge Mountain, and had fallen to his death on the descent. What a shock! He left behind a young wife in her twenties. Those of us who climbed with him were saddened by the news. I dedicate this write-up to you, my friend. Hope there’s good climbing wherever you are.

Thanks to Brian for the use of many of his photos.

Please visit us at our Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690