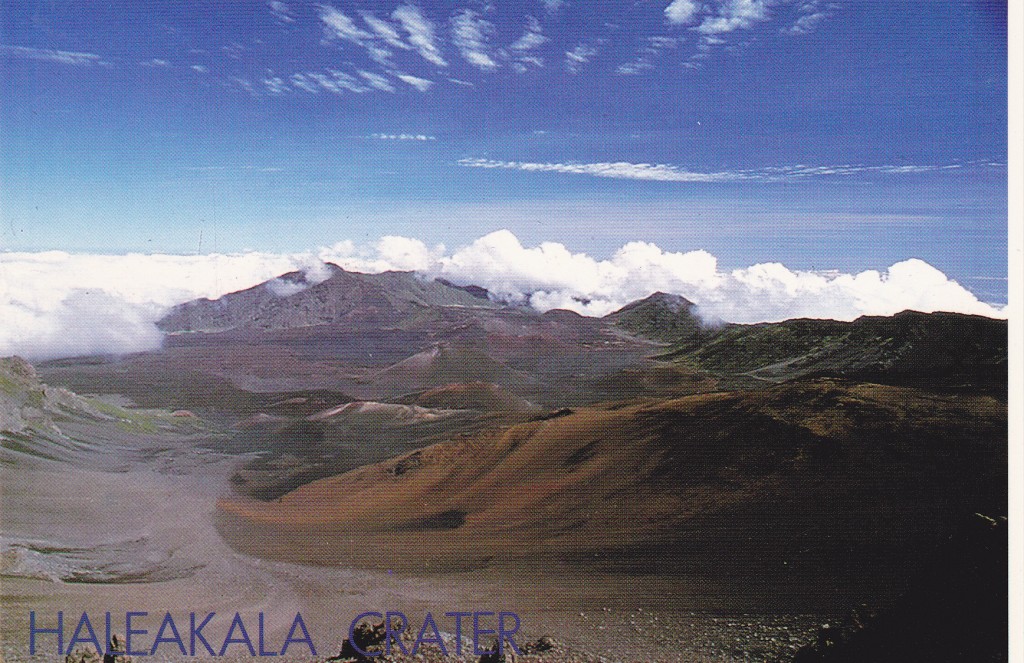

One late July day back in 1990, a friend offered me a free round-trip ticket to Hawaii. How could I refuse – all I had to do was fly out of Phoenix. Truth be told, she worked for the airline and could give away several such free tickets each year to friends or family. The only catch was that you had to fly standby. No big deal, right? I got on the flight my first try and, Bob’s your uncle, there I was in Honolulu. Then I caught a flight to Maui, and spent five glorious days on the island. One of the highlights was driving up to the top of Haleakala, the island’s highest point at 10,023 feet. Did it twice, in fact, spending the night sleeping in my rental car one of those times. It actually got down to 44 degrees up there. I fell in love with Maui – what’s not to like?

I flew from Kahalui over to Hilo on the Big Island. With another rental car, it was time to have some fun. The first day there, I drove over to Kalapana, or what was left of it. A new flow of orange-hot lava had made its way down from Kilauea volcano and had consumed most of the village. The place was crawling with locals and tourists alike, watching palm trees bursting into flame. The lava was flowing directly into the ocean along a 400-yard-long front. Until late that evening, the authorities let us walk up as close as we dared to the lava. What an experience! By the next morning, they had had a change of heart, requiring everyone to stay back a full 1/4 mile.

I drove up to the Kilauea visitor center, walked in the caldera, toured the lava tube and did generally touristy things. It, too, was a pretty cool place – they say it’s the world’s most active volcano.

The rental car I was using came with two warnings – you were not allowed to drive to South Point or over the Saddle Road. So, I drove down to South Point. How could I resist – the most southerly point in the 50 states. I walked on the green-sand beach (olivine, of course) and enjoyed the solitude, having the whole place to myself.

The next couple of days saw me visiting other tourist spots, living on the cheap by sleeping in the car and eating at Taco Bell, generally having a good time. But it was time to get serious, to do some climbing, so I drove up to the Saddle Road. Looked like a good road to me, couldn’t figure out what all the fuss was about. This is the road that passes across the island, separating the two huge volcanoes. Mauna Kea is the highest, and sits north of the road; Mauna Loa, south. From the high point along the Saddle Road, at 6,578′, an obvious sign pointed the way north up Mauna Kea. I’m guessing it was about 6 miles up the good paved road to the visitor center at a spot called Halepohaku, at around 9,200 feet elevation.

I had just come directly from sea level, so I didn’t want to overdo it by going too high too quickly. This seemed like a good place to spend the night. The road continued to the summit, but the public wasn’t allowed to drive it – I knew it’d be all on foot from here on in. It was still early in the day, so I parked and took it easy. There was a nearby cinder cone which I climbed for a bit of exercise and admired the view. I then pitched my tent next to the car in an out-of-the-way spot at around 9,500′, ate some food and finally walked over to the visitor center. It was a nice place, and there I watched an hour-long video about the observatory on the mountain top. They set up a 12-inch telescope for public viewing, but high altostratus clouds messed that up. The valley below had been socked in all evening, but finally cleared. I walked back over to my tent and turned in for the night.

At 5:30 a.m., it was 39 degrees and beautifully clear when I set out. Not wanting to feel nauseous, I didn’t eat anything – being a bit over-cautious, I suppose, but I didn’t want anything to ruin this day. There was a good footpath I followed, which was enjoyable because it stayed well away from the road. By the time an hour had passed, I had gained 1,400 feet – respectable, so I was pleased. The trail passed over endless cinder slopes, stark but beautiful. At one point I saw three hunters – I had no idea what they were hunting, but they carried rifles.

I started to slow down. Took aspirin for my slight headache, and a few antacids to make sure I didn’t get nauseous. Other than sucking on a few candies, I still didn’t eat anything. At 13,020′, I reached Lake Waiau, where I saw three mouflon sheep near the shore – perhaps that’s what the hunters were after.

Near the lake, my footpath regained the road, which I followed the last mile to the summit. It had taken me four and a half hours, and there I was, at 13,796 feet above sea level. A cool breeze was blowing, but the air was crystal-clear and the views were amazing. I could easily see over to Haleakala on the island of Maui, and over much of the Big Island.

A group of Japanese tourists arrived – they were school teachers back home, and we hit it off, taking pictures of each other and enjoying the scenery.

The most obvious feature on the summit area is the collection of telescopes known as the Mauna Kea Observatories. This is one of the best astronomy sites in the world, and it is festooned with instruments of all sizes. It may surprise some of you to learn that these high volcanoes can experience snow in the winter, as shown in this postcard photo.

We spent a short while on the summit, and when the teachers offered me a ride in their tour van back down to my campsite, I took them up on it. Once back at my car, I drove down to the visitor center and got cleaned up in the bathroom. After eating some lunch, I drove back down to the Saddle Road. It was short work to head about half a mile farther east to find the start of the next road I needed.

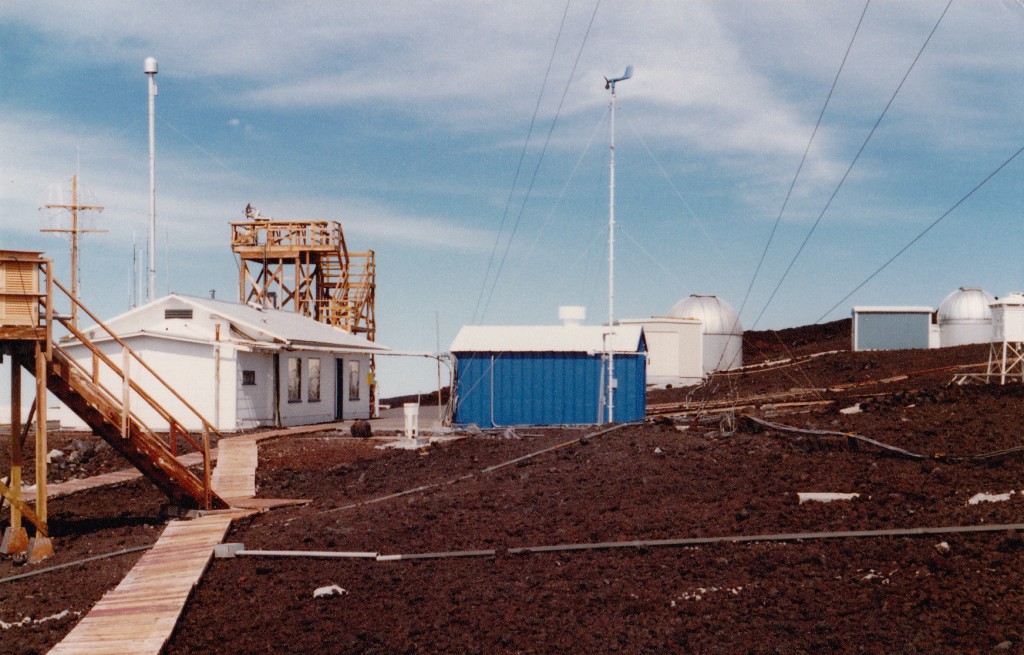

The reasoning went something like this: since I had just spent the last 24 hours up high getting acclimated, why not head over to the other big volcano and climb it while I was in the vicinity. This road too was paved, and led high up on the mountain. Seventeen miles in length, it passes through non-stop lava flows of every color and texture imaginable, both a’a and pahoehoe. I stopped once to go down inside a lava tube. At the road’s end, I parked by the U.S. Weather Station operated by NOAA, at 11,155′. It was cool and windy at 4:00 p.m. when I arrived. There was nobody at the station when I went knocking. Since there was no good place to pitch my tent, I decided to sleep in the car.

Haleakala and the telescopes on Mauna Kea were plainly visible from here. So were clouds that would approach Humu’ula Saddle from both east and west but would never quite meet, leaving the saddle itself clear and sunny. I whiled away the time into the early evening, listening to FM stations all the way from Honolulu, and snacking. Then, I locked the car keys in the trunk. Don’t ask me why – it just happened, okay! Luckily for me, I had left the car door open. What a predicament! Soon, a fellow came driving up – Brandon, who worked there. He fetched tools, we took out the back seat and then reached into the trunk to retrieve the keys. Whew, that was too close for comfort!

A young couple arrived, and Brandon gave all of us a tour of the weather station. It seemed an important place, many instruments feeding data about all aspects of weather and pollution into endless machines which record it all. After the tour, I retired to the car and drank a Hawaiian beer to celebrate my climb of Mauna Kea, then a few more to celebrate what I hoped would be a successful ascent of Mauna Loa the next morning. You can bet I didn’t let the car keys out of my sight.

During the night, I woke up to see a partial lunar eclipse – the visibility was excellent. Most of the night was spent in my sleeping bag in a sort-of-sitting position – not too bad a sleep, actually. When I woke up, I ate yogurt and granola and set off on foot by 6:00 a.m. The first part involved walking along a road for 800 yards to a trailhead. The sign said it was 6 miles to the summit. The trail then followed a series of ahu, cairns of piled rocks, over open rock areas (pahoehoe flows) for quite a while. Next, the trail joins up with the road again for a short distance, then heads across an easier area of fine cinders, where there were many lava tubes of all sizes with iridescent lava. Finally, a junction of many trails was reached at about 13,000′. Up until this point, the trail went up the long axis of the lava flows, making for fairly easy travel.

For the last 2.6 miles to the summit, you skirt the rim of the huge Mukuaweoweo Crater, or caldera.

In doing this, you cross many a’a lava flows, which is slow going. The floor of the caldera is very flat, almost four miles long and covered with smooth lava. Steam was rising from a few vents on the floor, and there were even some remnant bits of snow in the southwest part. By 10:30 a.m., I had reached the summit, marked by a huge cairn with a very full summit register. Placed by the National Park Service, it contained entries from people from all over the world. The sky was clear, a light breeze was blowing and the temperature was 60 degrees F.

They say the peak, measured from its base on the sea floor to its summit, is the world’s most massive, with 100 times the volume of Mt. Rainier. It is also said to be the most isolated land mass in the world, over 2,500 miles from any other. The caldera is huge. To reach a hut is ten miles around the rim, and it’s about 20 miles to circumambulate the whole thing.. Yesterday’s Mauna Kea is more like a normal tall peak, whereas Mauna Loa is vast and unthinkably spread out. To hike across it on trails consumes 22 miles; to drive from one trailhead to another, 87.

I spent perhaps half an hour on the summit – had the place to myself. However, all good things must end, so I left and started back down. At around 13,400′ I came upon a deep hole in the lava, it’s bottom filled with snow.

Otherwise, the descent was uneventful and took only two hours. I drove back to Hilo and flew to Honolulu. Then things went to hell in a handbasket.

I checked in with America West Airlines at the Honolulu airport and was promptly told that their flights were fully booked. At that time, they had two flights a day back to the mainland; one left at 1:00 p.m., the other at 9:20 p.m. Having a standby ticket put me on the bottom of the totem pole. There were plenty of others in the same boat, but if you were an airline employee, or family of an employee, you had priority. I didn’t make it on to the first flight – same for the evening one. Hmmm, not good.

The next morning, I was in line very early – the first, in fact. Didn’t help – no standbys made it on. Ditto for the evening flight. My third day produced no better result. Even if I were the first in line, the higher-priority ticket-holders got any available seats. By the third day, the ever-growing number of us standby types were developing a cameraderie. In line, a somber mood prevailed whenever the time for boarding approached. Clever comments started to circulate, such as: “It’s so quiet you could hear a plane drop”, and “Look at all these standbys, all dressed up and no place to go”. It’s safe to say that we were becoming pessimistic about our chances.

In the pecking order, I was a 4. That meant that 3s (family of employees), 2s (employees) and 1s (managers) all got a chance to board ahead of me. No matter how early I made it into line, all those others could board ahead of me. My fourth day produced no better results. You can believe me when I tell you that I was becoming VERY familiar with the layout of the airport. My cohorts and I wandered through every nook and cranny of the place, and I had grown to hate it.

Day 5 in the airport was grim. The line of standbys was longer than ever. People were dropping like flies, giving up and buying a ticket out on any airline they could manage. Desperate, I spoke to the America West supervisor – he swore he’d have me out on one of the flights tomorrow. I took him at his word, but if he didn’t come through, I’d cave and buy a ticket out on another airline.

Day 6 – the line of standbys was worse than ever. Someone told me of a cut-rate airline called American Trans Air. I went and spoke to them – the best deal they could offer me was a confirmed seat on a flight out at 2:20 p.m. for $105.00. I took them up on it. The race was run, and America West had beaten my sorry ass. I was never so glad to board a flight, before or since, as the one that afternoon.

Our L-1011 landed in San Francisco a little after 10:00 that evening. My plan was this – I could still use my standby ticket if I flew America West, and it was good to Phoenix. I spent the night in the airport – at least their seats were comfortable, compared to those in Honolulu. Day 7 of my saga dawned in the City by the Bay. I was the first in line when the ticket counter opened at 4:45 a.m. Didn’t help much, though – the first flight out at 7:00 a.m. was full and I didn’t make it on. Same for the one at eleven o’clock, but I managed to get on the 2:00 p.m. flight, and two hours later I was in Phoenix. There, I retrieved my baggage from America West, where it had been sitting for almost a week. The reason for that was simple – when listed as a standby passenger back in Honolulu on my first try out, they required us to check our bags, as if we were going to board. I caught a shuttle to Tucson and was finally home.

So ends my tale of the Hawaiian volcanoes. Sorry things got so sidetracked at the end. By the way, I won’t fly standby any more, and I cannot stand the sight of the Honolulu airport.

Please visit our Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690