When I go climbing, I’m not looking for adventure. What I mean is, I just want to get to the tops of mountains, that’s all. I’m not looking for anything outrageous to happen. However, sometimes things turn out differently when you least expect it. This trip started out well enough, but headed south half-way through. I’m getting ahead of myself, though. Let’s begin at the beginning.

It all started innocently enough. Andy had emailed me from Phoenix a few weeks earlier and suggested we head out to the Sauceda Mountains, one of our favorite places. September 18th, our appointed day, arrived. Weather forecasts had promised heat, and plenty of it – by then, we were so stoked to climb that nothing was going to stop us. In retrospect, maybe we should have reconsidered.

I left home, and in two hours, I had driven to a spot where I needed to leave the pavement. From this point, travel would all be on ever-worsening dirt roads, none of which I had ever driven before. I had in hand my permit from the Air Force, and that allowed me to dial up the current combination on the lock. If you follow the Air Force’s rules, you are allowed to visit parts of their bombing range. However, in order to get the permit, you need to sit through an instructional video warning you of the dangers of stepping on unexploded ordnance, and of smuggling activity. You also need to sign a hold-harmless agreement, which clearly states that if you get blown up or get mugged by smugglers, the government isn’t responsible. That’s a fair trade – accept danger in exchange for the privilege of visiting a beautiful area.

Once through the gate, I headed in a southeasterly direction for 11 miles. It was flat, with a few easy washes to cross, and I made pretty good time. En route, I decided to call Andy while I was still within cell-phone range of the town of Ajo, Arizona. He answered, and told me he was at least an hour behind me. No problem, we’d meet up later at an agreed-upon camp-spot. I had a peak in mind that I wanted to climb before calling it a day, and told Andy which one it was. He said he planned to climb one too, but wasn’t sure yet which one it’d be. Here’s a view of the peak I was headed for; this photo was taken from the south the following day.

My road merged with a better-traveled one, so I turned northeast and quickly covered a bit more than two miles. Then things changed dramatically. The road left the hard-packed desert floor and dropped into the broad wash known as Ryans Canyon. A wash is a sandy-bottomed dry streambed. They can be tricky to travel: deep sand can suck you down, even in four-wheel-drive; they can narrow suddenly, hemming you in with thick vegetation or rocky walls; they can change direction quickly, sometimes so dramatically that you can’t turn your wheels sharply enough to make the turn. Ryans Canyon was pretty straightforward as washes go, and well-traveled – that was a good thing, as we’d be driving it a lot this weekend.

It was all new ground, so I took my time. In a bit under four miles of travel in Ryans Canyon, I stopped at the side of the broad wash and parked. It was just after 4:00 o’clock and the temperature was a steamy 97 degrees. After organizing my pack (I took my time, as it was my first time out in four months), I started up the steep slope. The heat was brutal, the sun beating down on me, so the climb up the 800-foot mountainside was slow. At the top, a plateau greeted me. It was an easy half-mile walk to the north through the cactus, and it wasn’t too hard to find the bit that was the highest point of Peak 2786. There, I found a cairn, and inside it was a terracache left a year and a half earlier by an Ajo man, who had dropped the name “Prickly Pear Flats” on the spot.

One mountain that could be seen from many places in the area was Hat Mountain, and from where I stood, it lived up to its name.

The sun was setting, so I headed back south across the plateau and started down the steep slope. As the light faded, I studied the valley bottom – there was a faint road I wanted to drive to get over to our campsite, and from above I had an aerial view of the lay of the land. I studied it over and over, committing it to memory. When I reached the truck two hours after I started out, it was completely dark.

With the map beside me and my headlights on, I drove directly to what should have been the start of the road – but I couldn’t find it! With my truck thrashing through the brush, I went round and around – how could it have disappeared, it was so visible from above! Eventually I found it, but it was so faint it was hard to follow. I lost it a few more times, but after a lot of fooling around I finally reached the area Andy and I had picked for our camp. It was touch and go for a while – I was afraid of losing the road in the dark and having to stay put until daylight – that would set our climbing schedule back. Little did I know that Andy had been watching my antics from high above on a nearby mountain – the back and forth, the round and round. As soon as I parked and got out of my truck, I happened to be looking west and saw a light flickering in the distance – Andy was making his way down through the cliff bands of the peak he had climbed that afternoon. When he signed into the register, it was already dark – what a challenge he had in front of him! I watched him for a bit, then lost sight of his light.

Over the next hour, I busied myself with eating and preparing my pack for the climbing tomorrow. Then, in the quiet night I heard a sound – it was a vehicle revving up and moving around. It had to be Andy, and although he was a mile away, the sound carried easily through the still desert night. Right away, I knew that he too was having difficulty following the road. I honked my horn for several long blasts, and shone my headlamp down in his direction, but it went un-noticed. Eventually, the sound grew closer and I knew he was on track – it was probably nine o’clock when he pulled into camp. It was a good reunion, as we hadn’t seen each other since we had done a technical climb seven months earlier.

The alarm jangled the nerves at 4:30 AM when it went off. We quickly packed up, then drove another mile in the dark to where the road ended at a guzzler. This was a man-made water catchment, built there to provide a life-saving water supply for the desert animals. It was way off the beaten path, proven by the fact that there wasn’t a speck of trash left there by indocumentados. This guzzler was filled by collecting water from a rocky gully during rainfalls and running it through an underground pipe. Hundreds of bees lined its edges, drinking thirstily, while as many others, drowned, floated on the surface.

It only took us a few minutes to get ready to set out for our first objective, Peak 2768 at 6:00 AM . This was one both Andy and I had admired from afar for the last few years due to its steep pyramidal shape.

We made a beeline for a brushy gully which seemed to offer the most direct route to the upper part of the mountain. It worked, the worst of it being a few Class 3 moves in the gully itself.

The climb turned out to be a lot easier than we’d anticipated and we made good time. Most of the way up, we stopped to drink and admire the view. The last part of the ridge was easy, and before we knew it we stood on the summit of Peak 2768. Nobody had been there before us, and that’s always a bonus. Here’s a view of Hat Mountain and its neighbors from the summit in the early morning light.

Andy had devised a new type of register which had a lot of advantages. It consisted of two small nesting cans (the smaller was a tomato paste can, the larger was the smallest size of tomato sauce), both spray-painted a robin’s-egg blue. Instead of a glass jar, inside was a plastic bag with paper and pencil. The whole affair was extremely light and compact. Not using a jar meant there was nothing to break, and rocks could be stacked directly on top of it. It was quick work to build a cairn and place the register inside it. This was an important vantage point for views to other peaks in this part of the Sauceda Mountains.

Our descent went without a hitch, and we decided to not return directly to the guzzler but instead head west to another nearby mountain. The day was warming up, and we were starting to feel it by the time we reached the top of Peak 2490.

Another virgin peak, with no sign of any previous visit. I managed a call home – we were close enough to Ajo to pick up the cell site there. After half an hour on the summit, we headed back down to the trucks and arrived there about four hours after we had started out. It was getting toasty. Facing the guzzler was a motion-sensor camera that Arizona Game and Fish uses to keep track of who or what drinks the water.

With the advantage of daylight, it was an easy drive downhill all the way to Ryans Canyon.

There were great desert views on the way out.

Andy suggested a lunch break, so after a mile of heading west in the canyon itself, we stopped in the shade of a large tree. As we sat there eating, we heard a vehicle approaching from the east, and in a short while a jeep pulled up and stopped. It was Toby, a lifelong resident of Ajo – he had been up checking on a hunting campsite that he and his friends used a few times a year. He was as surprised to see us as we were him. We had a nice visit, and shared information about roads in the more obscure parts of the range. He finally took off, and by then Andy had decided to head home – he felt it was getting too hot, and not worth the stress of doing more climbing in the heat.

We convoyed down the canyon one more mile. My plan was to climb the peak Andy had descended in the dark the night before, so as we drove we examined the north side of the peak to search for the best route up. The problem was that large cliff bands ran all the way along that side, and I thought things would go better for me if I were to outflank all of them by going to the end of the peak, gaining the ridge, and doing a walk along its length. From the desert floor, it didn’t look too bad. In the next picture, the northern end of the ridge is Point 2454 at the top of the pyramid in the middle of the view, and that was the first place I wanted to reach. To the left of that stretches the long ridge heading towards the summit.

After moving my truck out of the wash, I watched Andy drive away and head west back towards the highway and home. Filled with optimism, I set out for the peak at 12:30 PM, heading across a stretch of flat ground and reaching the end of the ridge after about 1/3 mile. Dang, it felt hot! Maybe once up on the ridge, there’d be a nice breeze to help me imagine it was cooler than it really was. I mean, the summit was less than 800 feet above where I’d parked, so how bad could the climb be?

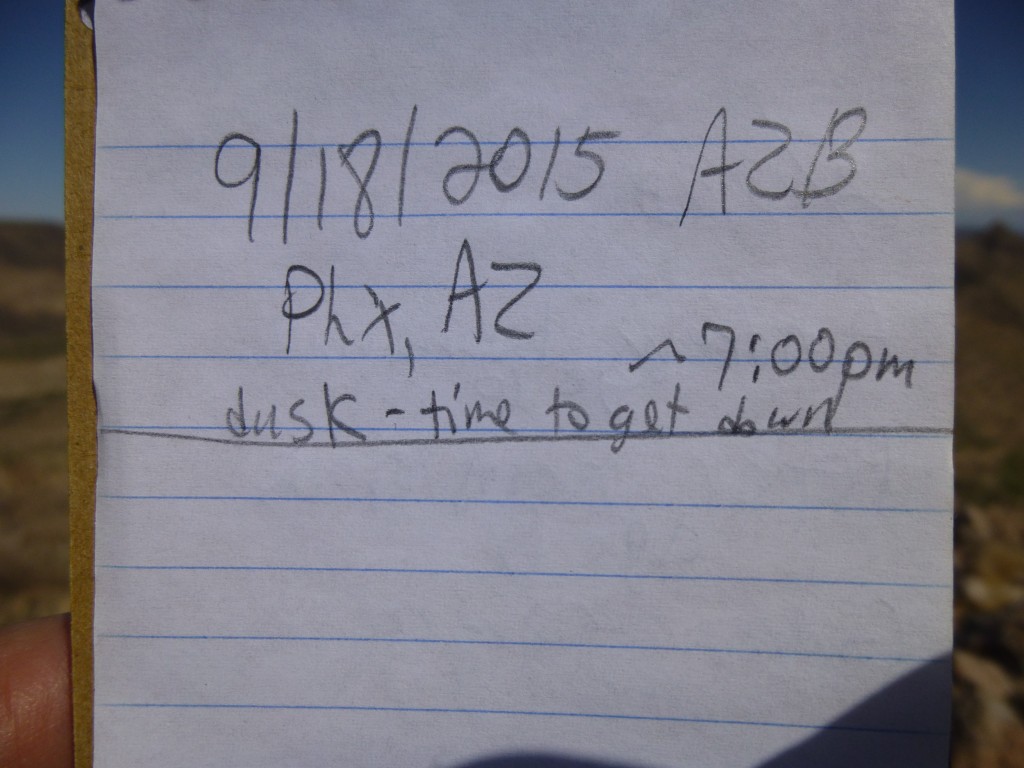

I labored up the slope, and after a while, reached Point 2454 at the northwest end of the ridge. There, instead of finding a nice easy ridge walk, it became apparent that it’d be nothing of the sort. The topo map had 40-foot contours for this peak. Now that’s pretty good detail compared to the maps available in other countries, but this ridge was about to prove that a lot of detail can be missing even with that interval. The map itself showed 5 closed 40-foot contours along the ridge, but there were SO many smaller bumps of 10, 20 or 30 feet that I lost count. It seemed like it would never end, and the farther I went the more tired I became. Finally, at 2:35 PM I staggered on to the highest bump. Naturally, this was the very last one along the entire ridge, at the opposite end of the ridge from where I’d started. The temperature was 102 degrees in the shade, and I felt like hammered dog shit. I found the register Andy had signed the day before.

I called Andy, who was still driving back to Phoenix, telling him I couldn’t bear the idea of running that entire ridge again. I told him I’d do anything to avoid it, hoping I could find a way down through the cliff bands instead. After all, he had done it by headlamp the night before, whereas I had the advantage of daylight. He said to move carefully to avoid getting cliffed out, and wished me luck. One last look around before I left captured this telephoto view of the amazing Tom Thumb only 7 miles to the southeast.

After I signed in and had a drink (I didn’t eat anything – such intense heat really kills your appetite), I started back along the ridge, only going a short way before finding a good spot to start my descent. Things went better than I expected – except for a bit of Class 3, it was all straightforward and I had no problems.

It was a relief to walk out on to the desert floor and start the one-mile walk back to the truck. By the time I reached it, the time was 4:30 PM and I was all done in. This climb had taken an outrageous 4 1/2 hours to complete. In retrospect, climbing that final peak may not have been such a good idea after all, pushing the envelope as it were. But, as I was about to learn, things can change in a hearbeat.

After a bit, I drove back into the wash. I was trying to see where Andy’s tracks led, the better to find my out of the maze of the wash’s channels, when something caught my eye. At that moment, my truck was facing east, the opposite way I needed to go, and a good thing, too. Perhaps 300 feet away was a man, walking towards me. He was half stumbling, half walking, and as he drew nearer I could see distress writ large on his face. I was sitting in the cab of my truck, the AC blasting, as he walked up to my driver’s-side door. This may not seem like a big deal, but a situation like this can turn horribly wrong in an instant. Were there others nearby who would jump me, take my truck and supplies, and leave me to die? It’s happened plenty of times here in the desert. He made a sign that he wanted water, so I cracked the window a bit, enough to talk to him. He was a Hispanic man, 30-ish, and he looked to be in pretty rough shape. Deciding he posed little threat, I opened my door and walked to the back of my truck, opened it up and gave him a gallon jug of water.

As we spoke, I learned he was with one other person who could no longer walk. He thanked me, then started walking back the way he had come. As he walked away, I realized I had to do more. I slowly drove towards him, and by the time I reached him he was with his friend who was sitting up against the bank of the wash. They looked rough, and I was convinced they were in no position to do me harm. Getting out of the truck, I went back and got them another gallon of water. Then we talked.

Francisco and Santos, both from Mexico, had crossed the border four days earlier, and in that time had covered about 50 miles to reach this point. That’s 50 miles as the crow flies. However, given the rugged country they’d crossed, it’s likely they’d actually walked 70 or 80 miles. They had done it on their own, had not been part of a larger group, and had used no coyote, or guide. They had nothing but the clothes on their backs, and not even socks on their feet. They must have had some pretty good blisters by this time.

It seemed appropriate to tell them more about where they were – I knew they didn’t have a clue. I told them they were in the middle of the Barry M. Goldwater Air Force Range, and a few miles to the north of their position was a broad expanse of desert where they dropped bombs and practiced air-to-ground target practice from A-10 aircraft. It’s a well-known fact that indocumentados often travel without maps, having only hearsay from others back home to rely upon. When I told them that the freeway, the goal they all shoot for, was probably at least four days walk through the mountains for an able-bodied person with plenty of food and water, I could see by the look on their faces that their hopes of reaching the promised land visibly diminished right then and there. It was hard to know how they’d react, but I then told them that if they wanted, I could call La Migra and they would be rescued very soon. Further, I explained to them that they would not be harmed in any way but would be treated with respect, and of course they would be deported to Mexico straight away. Without any hesitation, they said that that’s what they wanted, for the Border Patrol to come and get them. I further explained that I was not allowed to transport them myself, but if they stayed right where they were and didn’t move, I would relay their position to the BP and rescue could happen within hours. Yes, that was all they wanted, to be taken out of there as soon as possible. They asked me for some food, and I was happy to give them what I could spare. I needed to keep some for myself, as I was planning to stay out another night and climb three more peaks tomorrow – besides, I knew that as soon as the BP arrived, they’d be well taken care of.

Now I had to make good on my promise to get help, so once again telling them to stay put, I headed west a mile and promptly missed my turn-off out of the wash. Backtracking, I found it and then drove a couple more miles to a spot I felt would offer good cell-phone coverage. My call to the Ajo Border Patrol station went through right away, and the young agent was sympathetic to the plight of the men I’d found. I explained the situation to him fully. When he asked for the location, I gave him the UTM co-ordinates, which gave him pause. I told him I could convert it if given a while, but surely he had the technology to do it quicker. He said he could. Next, he asked me if those men had called 911 for help earlier – I told him no, it must have been someone else, as these guys had nothing but the clothes on their backs. He said they’d send someone out right away.

By the time the call was finished, the sun was almost down and I had a decision to make. If I stayed to climb tomorrow, I had to get to my campsite this evening for my pre-dawn start. Three peaks would eat up a lot of time, and in order to beat the heat I’d planned to start by headlamp an hour before daybreak. But, and it was a big but, I’d have to drive miles in the dark over what were unfamiliar and sketchy roads. Chances were excellent I’d lose the way several times, so I pulled the plug and started home. It’d be better to come back with daylight on my side.

It was now a race to cross the 11 miles back to the highway, and it went surprisingly well. The sun had set and the light was fading as I approached the highway.

Although my windows were closed with the AC cranked, I heard a noise that seemed out of place. A helicopter roared towards me, circled once, then flew off to the east. A short while later, on the highway, I came to the Border Patrol checkpoint to the south of Black Gap. As I pulled up to the agent on duty, he asked me how my day was going – I answered that it had become a lot more interesting the last few hours. When I told him about my encounter, he said “Oh, you’re the guy who called it in!” I asked if he’d heard some chatter on the radio, and he said the Ajo station had called them directly once my call had come in, as they were the closest group of agents to the two men. They had already dispatched a vehicle, and the chopper I’d seen was also theirs. The chopper had infrared technology which would quickly spot the men even in complete darkness, and could guide the vehicle right to them.

So, it seems my story had a happy ending after all. It was just dumb luck I’d run into those men, because the tiniest change in direction when I was leaving and I would have missed them altogether. It’s likely they would have been dead within a day – I can say that with some certainty, as I’ve run into situations like this several times before. It’s funny how things work out, isn’t it? It was not their day to die.

Please share this website with others, and follow us on our Facebook page at:

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690