On a perfect January morning, Jake and I left Tucson very early and drove about seventy miles to a point on Interstate 8. We found the gate we were looking for, allowing us to pass through the fence to the south of the pavement. After continuing a short distance, we came to the following sign.

We were about to enter the Sonoran Desert National Monument, a huge tract encompassing almost half a million acres. These lands were set aside by a decree of President Clinton in January of 2001, thereby protecting a huge chunk of pristine desert. It was near sunrise as we proceeded along the good dirt road and finally parked after less than three miles. We were at about 1,900 feet elevation. As we prepared to head out from the truck, the sun rose and illuminated the low desert country to the northwest.

The first thing we intended to do was to climb up to the top of a nearby hill called Indian Butte, the feature for which this map quad was named. It seemed pretty nondescript, but it was a convenient spot from which to survey the surrounding desert lowlands. It was the work of a few minutes to reach the top, and it afforded us a good view for our real objective for the day, the much higher Peak 3510.

We dropped down a few hundred feet to a saddle. Amongst the Palo Verde trees, we found a lot of items that had been left there. Jake counted eight backpacks in just one spot, plus a lot of discarded clothing.

This was obviously a place where undocumented entrants had waited. You have to wonder why they just left all that stuff. It seems unlikely they had been apprehended there, as the Border Patrol would not normally have gone up to that spot on foot. There was some interesting erosion on the nearby mountainside.

Continuing up the long ridge, we crossed a number of talus slopes, covered with dark volcanic rock.

Continuing up the long ridge, we crossed a number of talus slopes, covered with dark volcanic rock.

The ridge was several kilometers in length, but every bit of it was enjoyable. There was a nice breeze and bright sunshine, and the views in every direction were fantastic.

The ridge was several kilometers in length, but every bit of it was enjoyable. There was a nice breeze and bright sunshine, and the views in every direction were fantastic.

Only one bit was steep, while the rest of it was gently-sloped and meandering. We took our sweet time, so much so that by the time we reached the summit of Peak 3510, over three hours had passed.

The mountaintop was covered with a lot of large rocks. We knew that others had been there before us, so we started looking for a summit register. Try as we might, we couldn’t find one, so we decided to leave our own, something makeshift, maybe a piece of the map in a plastic baggie. However, almost by accident, we finally stumbled upon a glass jar containing papers and a pencil. We counted a total of sixteen prior entries, but nobody had been there for four years.

Looking south, we had an unhindered view of Table Top, the mountain for which the entire range and also the wilderness area had been named. Just to the west of Table Top was the second-highest peak of the range, known simply as Peak 3932.

Jake said that he and his wife had talked of doing some backpacking, and, as we gazed down to the valley below, the perfect trip was coming to mind. Why not walk in from the northern edge of the wilderness area, heading south up the long wash, then climb Table Top by its north ridge directly to the summit, a distance of about seven miles one way. It almost made me want to take up backpacking again.

We noticed an unusual marking scratched into a large rock on the summit and wondered if it were an Indian petroglyph. There were no others to be found, just that one, so maybe it was something done by a visitor in recent years.

The view to the east showed range after range of mountains disappearing into the hazy distance.

Looking to the west northwest, you could see right over nearby peaks and then all the way to the distant Gila Bend Mountains.

We had a good lunch, really taking our time, and signed in to the register, making sure we left it in a more-easily-found spot. As we descended the long ridge to the north, the day was perfect, with a gentle desert breeze and a temperature in the low 70s. It seemed that saguaro cacti really liked this area, as they grew thickly in several spots.

The miles passed, and we finally made it to a point where we had a good view down a steep slope to the north. Jake spotted what looked like a trail cutting across the mountainside hundreds of feet below us and suggested that we could go down to it and follow it out back to the area of the truck. It sounded like a good idea, so we descended to where we had earlier found all of the backpacks on the ridge. Once there, we dropped down a steep gully and eventually picked up the trail. It was pretty sketchy, and we wondered how it had shown up so clearly from above. We followed it into a gentle wash which meandered a lot and headed down into the desert away from the mountain slopes.

There were recent and obvious footsteps which we were seeing as we headed down the wash, as well as bits of cast-off clothing, empty bottles and more backpacks. Rounding a corner, we came upon a cave in the bank of the wash. Jake tried it on for size, and it was a perfect spot to wait out a storm, escape the hot sun, or avoid detection from Border Patrol aircraft that overflew the area.

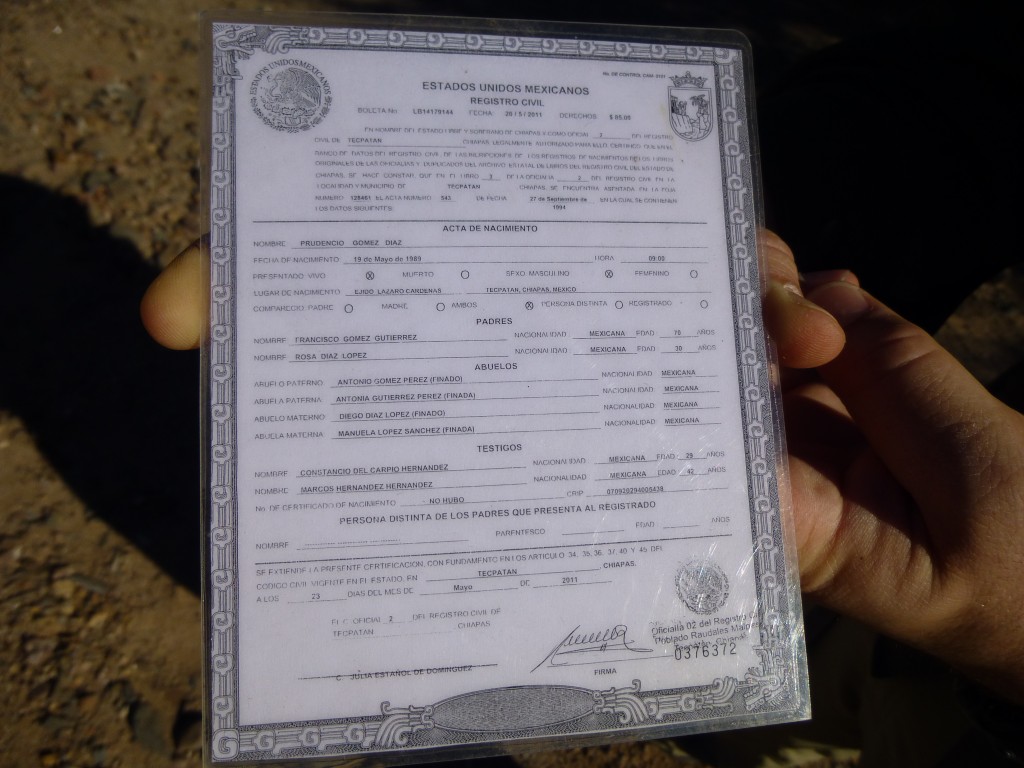

We came upon more discarded stuff, and something caught Jake’s eye. It was a well-laminated card, some sort of Mexican identification document. It was in perfect condition, in spite of the fact that it was exposed to the elements.

It belonged to one Prudencio Gomez-Diaz, who had been born on May 19, 1989. The card had been issued to him on May 23, 2011, only 20 months before we found it. This man was from the state of Chiapas, in far southern Mexico near the border with Guatamala. The card had been issued in the city of Tecpatan, and named his parents and grandparents. It also showed that he had been born on an ejido in that state, so it was safe to say that he had probably grown up the son of poor peasant farmers. His prospects there were next to none, so, newly-minted ID in hand, he decided to head for the border and the promise of a better life. Far fewer migrants were crossing the border these days due to the depressed economy in the States, yet he must have felt that the options were still better in El Norte.

This was an interesting find – I hadn’t seen anything like this in all my years of tromping through the desert. Jake kept the card and we moved on, wondering aloud what may have happened to this young man. We walked until the wash widened out, then headed cross-country until we reached the road we had taken in that morning. Once at the truck, we decided to drive the few hundred yards to the very end of the road, as something had caught our eye earlier that morning as seen from on high. It was a large tank.within a corral. It was obviously an old railroad tanker car, but metal bases had been welded on to it at each end, and the entire thing set up on massive concrete pedestals. There had once been a gasoline-powered motor there which operated a pump. That pump had served to pump water out of a well into the tank, and water from the tank passed through an underground pipe to a concrete cattle trough nearby.

All of this appeared to have fallen into disuse years before our arrival. Another one of those desert mysteries. We headed on out, back to the pavement, and were in Tucson an hour and a half later. The following day, Jake sent me an email with this attachment. His sleuthing had discovered more information about our friend Prudencio. It turns out that he had been arrested in Florida on April 7, 2012 for driving without a license, had posted bail and been released the same day. Who knows, maybe he was turned over to the Border Patrol and deported. At least he didn’t die in the desert like so many of his countrymen.

Please visit our Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690