Although I slept better last night, I was still restless – no doubt, I was excited about our climb. When we arose, we completely sorted all our gear and made up our packs for the mountain. Although lighter than when we walked away from Esteban’s place in Bolivia, they were still pretty heavy. We were carrying 7 liters of water with us, which added to the weight. Glassing the slopes of the mountain from the refuge, there was no sign of the two Americans. We had no idea how they were doing. From our side, we hoped we could reach snow-line today.

The head ranger, Carlos, arrived late at the refuge. We paid our bill and said goodbye to our British friends, then threw our gear into his vehicle and drove away. He and his assistant took us to the road-end at about 14,800′, and wouldn’t take a dime for their efforts. These genuinely nice guys wished us well and drove away. There we were, just the mountain and our hopes. Shouldering our packs, we set off.

Parinacota’s snowy head just poked over a nearby hillock. See the bit of green yareta moss – it seems to be able to grow in the harshest places.

The going was quite flat, nothing but dust and cinders. As we started out, we spotted the yellow tent of the Americans, high up on the south slope. They had covered a lot of ground to get where they were – our line would be on the southwest side, some distance from their position. After a while, the slope gradually steepened – we plodded along, one foot in front of the other.

The cinders gave way to more solid ground, if you could call it that – a sort of eroded rock that afforded some purchase for our boots, but still fairly rotten. It was a real slog. The hours passed, and we became more tired. By late afternoon, we were totally knackered. We had reached 16,960′, and had stopped there because we felt played out. It certainly wasn’t because we had found a good campsite – the slope was fairly steep, and we spent a long time leveling out a space for the tent. We didn’t excavate into the hillside, but, rather, piled up a lot of rocks to create a more-or-less level spot – it was barely serviceable. What a campsite – the climb went straight up from here!

Both of us had headaches, so we took aspirin, and some antacid for good measure. One of the first symptoms of altitude sickness, or acute mountain sickness, is nausea. As you climb higher, the partial pressure of oxygen drops. As your body tries to compensate, excess acidity can build up in your stomach – taking antacid can go a long way to relieve the feelings of nausea.

Brian wasn’t feeling well. I made some tea and a freeze-dried meal, but he didn’t partake. That could be a problem – the more time that passes without eating, your energy wanes. And dehydration at altitude can be really debilitating. Of course, if you’re feeling nauseous, it’s hard to keep anything down, liquid or solid, let alone convince yourself to swallow it in the first place.

The sun set at 6:15, and the temperature plummeted. We had good sleeping bags, so planned on a warm comfy night. It was snug in the tent with a bit of gear. I set my watch alarm for 3:00 a.m., hoping to set out by 4:00.

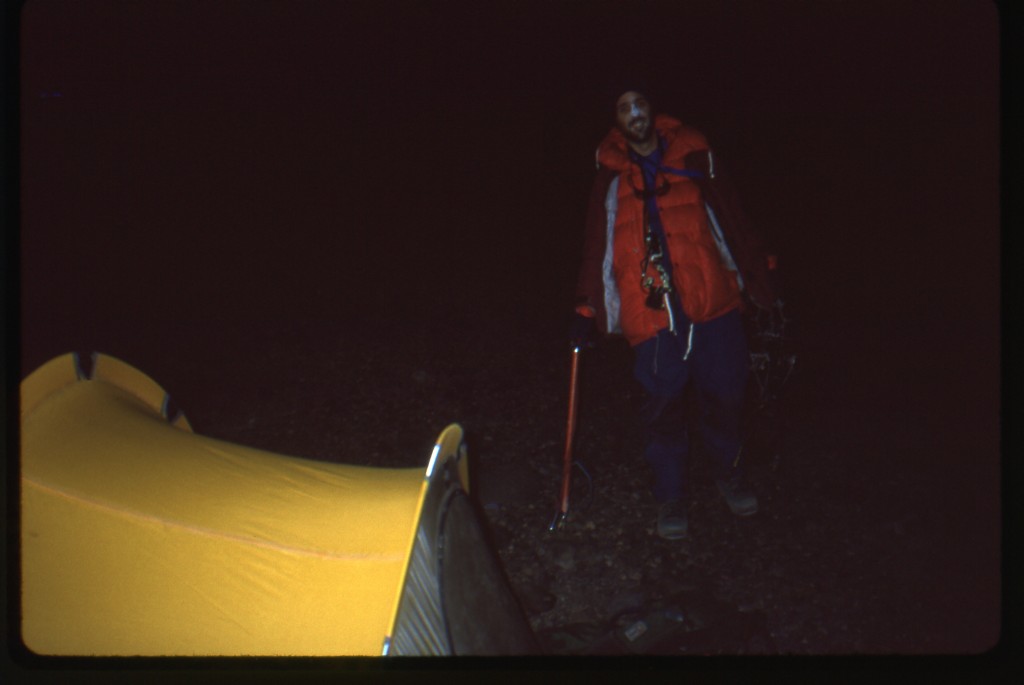

That bloody alarm sure went off early! I really didn’t want to get out of that bag – the cold was biting. Brian said he wasn’t feeling well, and had decided to stay at camp and rest. It was a shock, as it was a major change of plan, but I understood completely – I have had my share of nausea at altitude, and it sucks. You just want to curl up in a ball and die. I wasn’t highly motivated to go for the summit alone, but somehow forced myself to go through the motions of getting prepared, and by 4:10 a.m. I was ready to leave. Brian wished me well and told me to be careful up there. It was with some misgivings that I walked away from the tent into the night.

Man, it was cold. I was dressed for it, though, with plenty of layers. Carrying no pack, I had everything I needed in my many pockets. The clear night sky was ablaze with all the glory the southern hemisphere has to offer. I climbed by moonlight for an hour without using my headlight. Night climbing always feels weird to me – I get spaced out, almost like I’m hallucinating. I lose all sense of time.

After a while, when I was leaning on my ice axe catching my breath, I heard an unmistakable sound on the slope down below. It was the telltale clink of an ice axe ferrule going into hard snow. Wait a minute, that could only mean one thing…….. “Hey Brian, is that you?” After a pause, he replied in the affirmative. I switched on my headlight so he could see my position. I stayed put while he climbed up to me. He said he’d decided to climb after all, that he “didn’t want me up there alone”, even though he had a bad headache and was still nauseous. As long as I live, I will never forget that selfless act, the mark of a true friend. That’s why Brian is, to this day, someone in whose hands I would place my life, without any hesitation.

As we climbed on into the night, the moon set – it was very dark for almost an hour. Then came first light.

Our progress was very slow – the first 1,200 vertical feet took us four hours. We then arrived at our first real challenge, a huge field of nieves penitentes.

These are tall thin blades of ice, and as you study the pictures in the link, you can easily imagine what an obstacle they would present. Ours were about 2 feet high. You need to be very careful making your way through them, so as not to twist an ankle or lose your balance and fall onto them – they could do some real damage. It was painfully slow going up through them. I don’t recall how far they extended, but it could have been as much as a thousand vertical feet – they really took a toll on us.

The hours sped by while we lost all track of time. After the penitentes, we slogged our way up endless snow slopes, rock-hard early in the day but softening up later on in the full sun. In only a few spots did we see the tell-tale crease of a hidden crevasse, but these weren’t a problem, as they were well filled-in.

We ate and drank very little, no doubt weakening ourselves further in the process. The slope was a fairly uniform 40-or-so degrees, but without any surface features with which to judge scale or distance.

By 1:45 p.m., we figured we were less than 1,000 feet from the summit, but not sure exactly how far. It was decision time. It was crucial that we pick a turn-around time, a time by which we must absolutely start back down the mountain. One thing we knew for certain was that we didn’t want to get caught out on the mountain by the time darkness fell – spending a night out in the open would be bad business. Any turn-around time must give us enough time to safely descend the almost-4,000 vertical feet to our camp. In our wisdom, we decided that 4:00 p.m. would be that time. (In retrospect, it would have been disastrous to have been on the summit and only starting down that late in the day.)

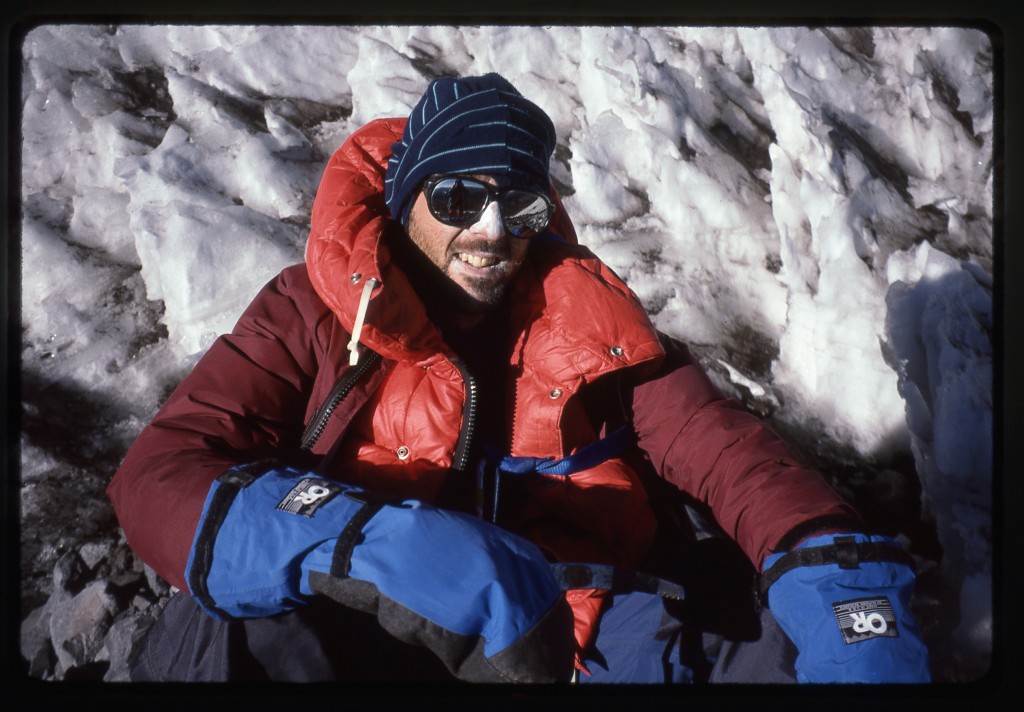

The going was slow as the afternoon progressed. It was still hard to tell how far it was to the summit. I saw some black rocks up above us on the open slope, the first feature we had seen since stepping on to the snow six hours earlier. It was impossible to tell how large they were, but they seemed to be close to the top. I dug deep, found a big burst of energy and climbed like a madman. The rocks, once I reached them, turned out to be an open area of mostly dirt, free of snow. It turned out that heat from the dormant volcano was escaping up through the crater lip and keeping the area free of ice. You could actually see the steam and smoke escaping from the fumaroles. A few more feet and there I was, standing on the top of the slope. I shouted down to Brian that I was there and it was done. Here is a shot of Brian coming up the last bit.

We were there, and it was 2:30 p.m. The wind was fierce, so we tried to hunker down to stay out of its blast. Here is a shot with Sajama in the background.

Out came the cameras, and we took plenty of pictures. The temperature was zero degrees Fahrenheit, and the wind speed was a brisk fifty miles per hour as it roared over the crater lip. As we scanned the edge of the huge crater, it became apparent that we were not on the highest point. We stood on the southwest part of the crater rim. It looked like it was a bit higher over on the southeast rim, and probably higher yet on the northwest rim.

We didn’t know how far around it was to reach both of those points to be certain we stood on the very highest spot. Because we had no good information, we would have had to visit both of those points to make sure we hit the true summit. Those distances were unknown, so it was possible it could take hours more to accomplish this. It wasn’t worth the risk of eating up that much daylight and not leaving ourselves enough time to get back to camp safely. Discretion is the better part of valor, especially in climbing. In this next shot, we are looking across the crater to the north – on the left skyline can be seen the summit of Pomerape, elevation 20,605 feet.

We had no GPS on this climb, and no detailed topographic map. However, since our visit, other climbers had circumnavigated the entire crater rim and had accurately determined the high and low areas. It turns out that Brian and I had stood at a point which was 46 feet lower than the true summit – we had reached 20,762′, whereas the highest point was 20,808′. We had no regrets. Most climbing of this nature is probably 25% physical and 75% mental – there are a hundred excuses you can come up with to talk yourself out of keeping on to the summit. Given how he was feeling, Brian’s getting up here was a tremendous feat, one that only a select few could ever have accomplished.

The climb up had taken 10 1/4 hours. It was hard to tell how long it would take to get back down to camp, but we needed to drop almost 4,000 vertical feet, so we didn’t have the luxury of time to linger on the top. Fifteen minutes was all the time we spent, then started down. It was steep, with a lot of rough snow, and slow going in places, even with ice axes and crampons..The huge area of penitentes was hell to negotiate in our tired state, and it was a big relief to be through them. At about 18,000 feet, Brian told me to go on ahead, that he would catch me up in a bit.

By the time I arrived at the tent, 3 1/2 hours had passed since we had left the top – pretty decent time. Brian arrived 20 minutes later – turns out he had to stop twice to vomit on the way down. It was dark by then.

He went straight to bed without eating anything – his nausea made it impossible. I fixed another freeze-dried meal and ate the whole thing. The air temperature must have been really cold – an inch of water I left in the pot froze solid within ten minutes. The full moon and the southern cross put on quite a show. It had been a great day of climbing. Nobody got hurt, and we had an amazing experience.

Stay tuned for the next installment of the story, entitled “Crossing the Border into Bolivia”.

You can also visit us at our Facebook page at: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690