It looked like I was pretty much done with climbing in the Sauceda Mountains of Arizona, that the range was all climbed out. Over 90 peaks and countless memories, nearly all of them good, but then I got to thinking that there must still be other things to climb in there – I just couldn’t stay away from the area, it was so amazing. So what do you do when you’ve climbed everything that clearly fits the definition of a peak? Well, how about climbing the things that don’t fit the normal definition? Here’s what I mean.

The standard commonly used in the southwestern part of the USA is that a peak must have at least 300′ of prominence. To measure that, you drop down from the top of the peak to the highest saddle which separates it from the next highest peak. So, once you’ve climbed all of those, what else could you do? You could move on to peaks that could interpolate to 300′ of prominence. The maps climbers prefer to use here are 1:24,000 scale, or better than 2.5 inches per mile, which is a really good scale. Those maps usually have 40-foot contours, and sometimes even 20-foot and 10-foot contours. Even with that, sometimes a summit will not have a precise elevation, so all we can do is assume that its elevation is somewhere between the highest contour shown and what would be the elevation of the next higher contour if there were one. Here’s an example – click on this link.

When you do, you’ll see a mountain-top with gentle contours at a 40-foot interval. The highest is a 4,920-foot contour, and here’s how we know – the highest numbered contour is 4,600 feet. You can see another heavy line within that one, enclosing a smaller area, and that is the 4,800-foot contour. If you keep counting, you can see three more fainter contours inside that one – they are the ones at 4,840′, 4,880′ and finally, 4,920′. But it is safe to assume that there is some higher land inside the 4,920′ contour. How much higher? Well, in theory it could be almost all the way up to 4,960′, but not quite all the way there, because if it were all the way to 4,960′ there’d be another contour shown at 4,960′. So how high is this peak? It’s higher than 4,920′ but lower than 4,960′, so for the sake of convenience so we can talk to each other about the peak, we interpolate the height as 4,940 feet – in other words, we split the difference, picking an arbitrary point half-way in between 4,920′ and 4,960′.

So, to make a long story even longer, there are plenty of peaks out there where, if we interpolate their elevation, they could have 300′ of prominence – so, just to be sure and eliminate any doubt, we climb them anyway. That’s how a whole other layer of peaks opened up, and I was hungry for the chase. There were now 38 additional targets I could pursue in my beloved Saudeda Mountains.

Once I’d made the decision to start on that new list, I realized that a weekend of nice, cool temperatures was coming up, so I loaded up the truck and headed out. To get the peaks I wanted, I’d have to drive through the Indian reservation, another of my favorite areas. By the time I’d finished packing and left home, it was almost 1:30 PM. I left the pavement at the village of Kaka and headed west for 3 rough miles along the El Paso Natural Gas pipeline road, then northwest on a worse road up the Kaka Valley. Still, the road was pretty decent for another 6 miles or so – sure, there were the usual annoying washes to go through, but nothing worse than high-clearance, which I have in spades with my old Toyota truck. Along the way, I saw the mighty Dragon’s Tooth rearing up above a nearby hillside and snapped this telephoto.

The topography changes quickly after that, as you cross the height-of-land at 2,600 feet and drop down into a different drainage. Right away, the road goes all to hell, and I’m talking about the seventh circle of hell, not the first – I know Dante would agree. I put it into four-wheel-drive and held on. In recent years, there must have been some awful rainstorms in the area. In one spot, the road had been badly eroded on its downhill side. I managed to creep across, but as my rear wheel passed the narrow spot, it slipped and my truck almost went over the bank. It was enough to put the fear of God into me. More carefully than ever, I motored on. At one point, I passed the remains of an old Ford Ranger, which had had the courtesy to break down over to the side of the road and not in the middle.

The road was badly overgrown in places – not only were things growing up in the middle of it, but were also pushing their way in from the sides. Several times, I couldn’t see it at all, and had to get out and walk ahead to find it again. My poor truck! I’m used to having it scratched by branches, but this was something else. An hour and a half after leaving Kaka, I had reached the farthest point I could drive. It was 5:00 PM and I was glad to be done – that road had worn me out.

After a pretty good night’s sleep, I arose at 5:00 AM, and spent time hiding my food and water, as well as extra gear, in the vicinity. My mountain bike was ready to go, and by six o’clock I was too, and pedaled away. The road, such as it was, was eroded and overgrown, and obviously hadn’t been driven in many years.

As you can see from the above photo, the road was rough in places. Many rocks, vegetation, sometimes sand – this made for some slow going. I had covered some distance before the sun rose.

One thing the map doesn’t show are all the gullies (here in the desert, we call them washes) that ran across the road. Some of them were only one or two feet deep, but most were from five to fifteen. There were dozens of them that I had to cross as the miles rolled by, and a great many of them forced me to get off the bike and walk it across. Some of our washes can be as wide as a small river would be in other places.

Well, the miles passed, as did the hours, and I finally reached my peak. It was a quick climb, not much to it, really, but I left my register on top – after all, I had carried it many miles for just that purpose. A less impressive peak you’ve never seen, and I can’t even tell you which one it is because of where it is. I will say this, though – there was some interesting stuff in the area – like this thing on the slope of my peak.

This thing must have fallen from the sky. Did it explode on impact? There were chunks of metal lying around, and the rock for several feet in every direction was white, like it had been scorched. This big metal thing was embedded a few feet into the solid rock of the hillside. Impressive.

Once down at the base of the peak, I explored a bit and found even more interesting stuff. Check this out.

And this one, which looks similar but different.

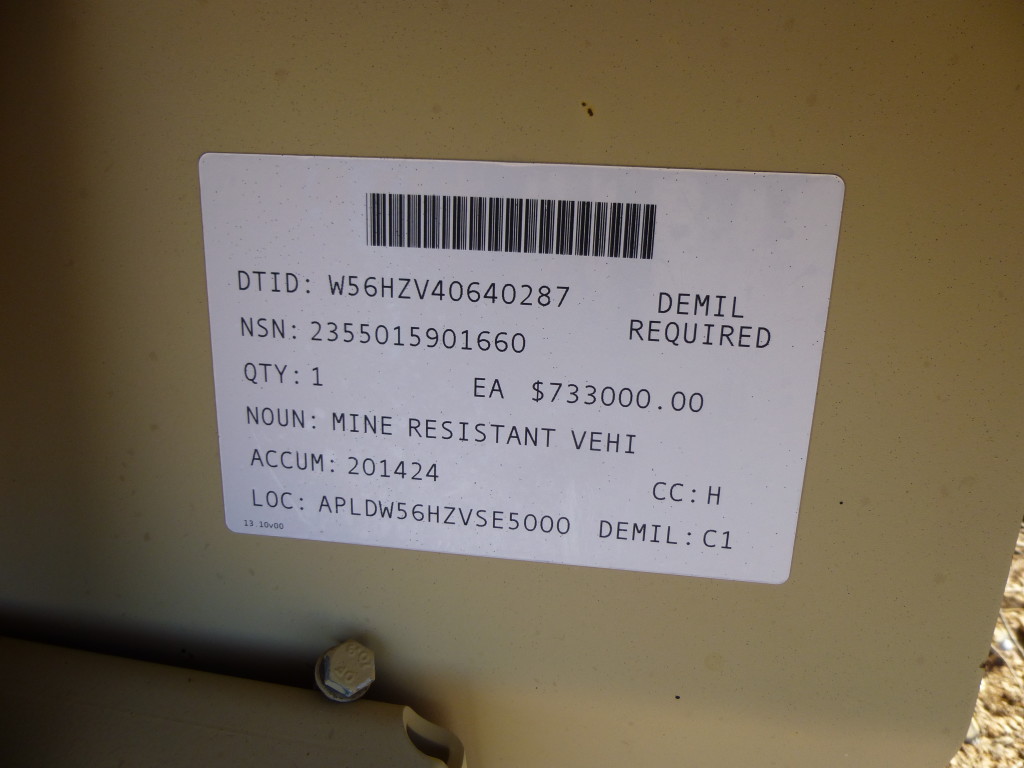

As I poked around, this tag on the above vehicle caught my eye.

Are you seeing the same thing I am? Does this mean that that one mine-resistant vehicle cost the military the sum of $733,300.00? Holy crap! There must be a lot more to it than meets the eye – either that, or it’s the fact that the military pays way too much for everything. Then there’s this one.

And this view inside it.

And then there was this one.

And one more.

Probably 20 minutes was spent roaming around this military vehicle showroom out in the middle of nowhere. It’s hard to know for sure what its purpose was. Unlike other vehicle groupings I’ve seen in other remote places, these weren’t all shot full of holes. There were well-maintained roads converging on this spot, quite unlike the old, tired road I’d ridden in on. When I’d reached this spot earlier in the day, I was quite surprised, as I wasn’t expecting anything at all out there. In fact, as I approached, I could see the vehicles in the distance and I became afraid of what I might be getting into. I got off my bike and stood behind a tree, observing for a while, trying to detect any movement among the trucks. Only when I was sure there were no people there did I approach.

It was time to start the many miles back, and that I did. The miles passed quickly enough. At one of the road junctions, I came upon this marker I had left earlier. Why had I left it? – just in case I was overly-tired, delusional from the heat or otherwise not thinking straight when I’d come back to this point.

By the time I finally pedaled down the last hill to my truck, I was all tuckered out. Riding a bicycle on rough roads is not my forté. I was off to my next climb, pondering the adventure of the road less traveled.

Please visit our Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690