Dave and I had been climbing for a few days in Arizona. That done, we moved east and spent the night in Lordsburg, New Mexico – dang, it was cold! The next morning, we headed over to Mickey D’s to get warmed up. I was in the mood for something filling, so when the cute Hispanic teenager behind the counter asked me what I wanted, I told her “flapjacks”. She didn’t bat an eye, and rang up an order of pancakes without hesitation – I was surprised that she knew what I’d meant because it’s such an old-fashioned term. She told me they had tourists from all over the country passing through, and she’d taken some pretty crazy orders. Some had ordered “a potato” when they wanted French fries or hash browns, so mine wasn’t too weird after all.

As we pulled into the parking lot, a Greyhound bus was leaving from the nearby curb and heading to the freeway. Inside the restaurant, a disheveled-looking fellow was excitedly asking other patrons when the next bus to Tucson would come by. It turns out he had been a passenger on the bus we’d seen leaving and had lost track of the time when he was inside getting a coffee. His luggage was on that bus, which he’d been riding for 2 1/2 days from the Carolinas. He was working his cell phone to try and resolve the issue. Seeing us getting ready to leave, he asked if we were going to Tucson. Dave informed him no, that we were going out to climb in a nearby mountain range.

Breakfast done, we headed out to I-10 and back towards the state line a mere 20 miles away. Our exit was a place called Steins, claiming to be a ghost town. There were a few ramshackle buildings, all in all a sorry lot. The dirt road cut through them and across the railroad tracks before heading out into picturesque ranching country.

Dave had pre-programmed waypoints into his GPS, making our travel north easier. About 8 miles later, we turned west up a broad valley called Doubtful Canyon. Man, the mountains were as pretty as you could ever hope for, like something out of a Zane Grey novel.

Four different tracks headed west, eventually merging into one, which delivered us to a locked gate at the Arizona – New Mexico state line. We had arrived at the Hooper Ranch. Dave parked his truck out of the way a few feet north of the road, at an elevation of 4,750 feet.

The sun had risen, taking the chill off the day, but a light fleece still felt good. Our peak was in plain view a few miles to the north, and to get there we’d start along a fence line on the New Mexico side.

A mile later, hard by a survey marker which clearly identified the state boundary, we climbed over a fence and followed it to the northwest, entering Arizona in the process.

The route crept across a gentle slope for a while as we followed an excellent route description, complete with pictures, published by Scott Surgent.

A mile from the surveyed fence corner had us at 5,100 feet and looking steeply north – here, we would leave Little Doubtful Canyon and really start to climb. The summit was still 1,500 vertical feet above us.

We stopped often, not only to catch our breath but also to admire the view.

The route took us to the left of the 3 rock faces just to the left of center.

Once on top of that, we had a good look back down the canyon we’d ascended.

The view up was even better – we’d stay to the left of the whitish areas.

We passed beneath a large overhang, which was a prominent feature along our route.

After that, more side-hilling, then a steeper bit.

That brought us to a steep notch with a bit of Class 3, but that was the toughest part of the whole climb.

Above that, it was an open slope up to the final, easy cliff band. What you see here is the last 700 vertical feet. The actual summit is visible, just above the cliffs on the skyline, a bit left of center.

Once on the summit ridge, it was a short walk west to gain the last 50 feet to reach the highest point of C. E. Uncertain Benchmark, at 6,540 feet elevation.

The summit itself was no great shakes, but oh, the long views in every direction made the whole climb worthwhile.

Some long telephoto views of snow-covered peaks in the distance – here’s a look to the south to the Chiricahua Mountains in Arizona. Zoom in to see the snow, 40 miles away.

If you looked to the northeast, you could see high peaks 65 miles away in New Mexico, over 10,000 feet in elevation and also covered in snow.

And of course we can’t forget our own Mt. Graham in Arizona, over 10,700 feet and 53 miles distant to the northwest.

Several of us later pondered by email, at length, the name of this benchmark, poring over survey information and everything else we could get our hands on. When surveyors move through an area, they seem to have free rein to name their benchmarks anything they please. The answer that made the most sense here was it meant “control elevation uncertain”.

There’s no shortage of colorful mountain names in the vicinity: Orange Butte; Roostercomb; Gazelle BM; Winchester Peak; Engine Mountain; Horsefoot Mountain; Midway Peak; Horsecamp BM; Gold Hill; Deadman Ridge; Redrock Mesa; Little Juniper Peak; High Lonesome Peak – those are all official names. Then there are the unofficial ones dropped on other nearby peaks by climbers and locals: Indian Spring Peak; Bellowing Bull Peak; Fortress Uncertain Peak; Moderately Uncertain Peak; Owl Head Butte; Bear Sign Peak.

It was a chill wind blowing as we ate a leisurely lunch on the top. Most of the register entries were old friends who had beaten us to the top years before, so we were in honored company as we signed in.

We spent maybe half an hour on top, then started back down, retracing our steps – the descent certainly went quicker than the climb up. The day was fine as we walked through the lowlands back to the truck, arriving after a 6-hour round-trip.

We had heard a few tantalizing bits of the history of this area, and decided to make a small pilgrimage to a grave that was marked on the topo map. It took a bit of looking around, but we finally found it. It sat on the lowest northwest slope of Steins Peak, out in the open. Here’s a picture of the area where the grave sits.

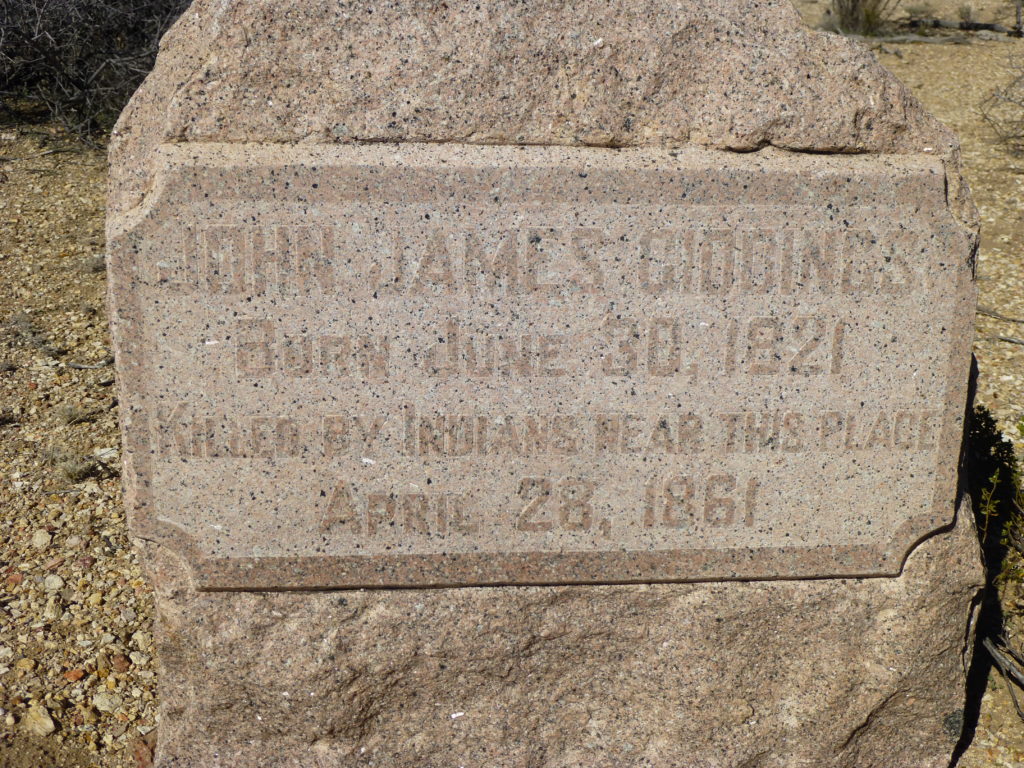

As we approached the grave, here’s what we saw.

And here’s a look at the headstone.

This beautiful pink marble headstone and plaque had been placed in recent years by a historical society which felt that the deceased deserved better than the unmarked grave which sat there, almost forgotten, for more than a century and a half. I’ll tell you more about the occupant in a bit, but first some history.

For thousands of years, Native American peoples have traveled through the mountains along this route. After them had come Spanish explorers from Mexico. Once they were gone, came the Anglos. Starting in 1843, pioneers started coming through and the route began to be called the Emigrant Trail. Later, a company called the Jackass Mail Line used the route, and did so from 1857 to 1861. Meanwhile, the Butterfield Trail and Overland Mail Company was using the same route from September 1858 to March 1861.

Now enters an important piece of history which would have far-reaching effects, known as the Bascom Affair. Here’s what transpired, and the timing is everything.

On January 27, 1861 in this area of the southwest, a group of Apache Indians stole some livestock and kidnapped a 12-year-old white boy. Lieutenant George Bascomb and the infantry were ordered to recover them. He convinced a Chiricahua Apache leader named Cochise to meet with him to discuss the issue. Cochise said he didn’t do it, and knew nothing about the incident. Bascomb didn’t believe him, and held Cochise and his family. Cochise escaped, then asked Bascomb to release his family. Bascomb said he’d only let them go when the 12-year-old boy was released. Cochise was furious!

In retaliation, Cochise and a large party of Apaches attacked a group of American and Mexican mule-team drivers. They tortured and killed the 9 Mexicans and took the 3 Americans hostage. Cochise then offered to exchange the 3 men for his family, but Bascomb flatly refused, saying he’d get his family back only when the boy was released. On February 7th, Cochise attacked Bascomb’s soldiers. Some historians feel this marked the start of the 25-year-long Apache Wars.

Cochise then fled with the hostages to Sonora, Mexico where he knew he was out of reach of the American soldiers. En route, he tortured and killed his 3 hostages, leaving their remains to be found by Bascom. On February 19th, the Army hanged Cochise’s brother and nephews. When Cochise discovered their bodies was the moment when the Chiricahua Indians transferred their hatred of the Mexicans to the Americans.

Felix Ward, the kidnapped boy, was later found with the Coyotero Apaches. So, it was true that the Chiricahua Apaches had had nothing to do with his kidnapping. He became an Apache scout for the U.S. Army, known by the name of Mickey Free. Among other exploits, he served as a scout for General George Crook in pursuit of Geronimo.

Which brings us back to the main story line. Because things were becoming so hot between the Anglos and the Apaches in the stretch from Doubtful Canyon to San Simon and Apache Pass, Butterfield quit running through the area in March of 1861. Meanwhile, the Giddings brothers had set up a company to transport passengers and mail from San Antonio, Texas to San Diego, California. They had started in July, 1857 and offered new coaches drawn by 6 mules accompanied by an armed escort. The simple fact, though, was that they were trying to operate a business through dangerous Apache lands, all because Bascom had started this affair with Cochise.

On April 23, 1861 a provision wagon which had passed through Doubtful Canyon was reported missing. A stage coach traveling the same route 4 days later also failed to arrive. Even worse, when 2 badly-bruised mules from the ill-fated stage returned, everyone feared that Cochise had led an attack. One of the Giddings brothers recruited 25 men to search the area, and they found pieces of harness, newspapers and mail – and human remains.

The following was reported in the Mesilla Times:

The stage station in Doubtful Canyon had been burned, the corral wall had been burned, and the Indians had formed a breastwork around the springs. Near the station, the bodies of 2 men were found, tied by feet to trees, their heads reaching within 18 inches of the ground, their arms extended and fastened to pickets, and evidence of a slow fire under their heads. The bodies were pierced with arrows and lances. They were so disfigured as to render recognition impossible.

So there we stood, Dave and I, pondering all of this on the lonely prairie where John James Giddings died 156 years earlier. It was a sobering experience.