When I was finishing my third year of studies at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, something was becoming very apparent to me – I knew I wouldn’t get a job when I graduated. I was one year shy of getting a Bachelor of Science degree in Zoology, and it was a pretty well-known fact that you wouldn’t get a job with that particular degree. A Master’s degree would have made things easier, but with my grades there was no way I’d ever get into grad school. It was the spring of 1967, and I made the big decision to switch my major to geology. It meant an extra year in school, to make up all the courses I would have missed so far, but that didn’t bother me. Geology was the hottest field out there, at least in BC. The following year, one company offered to hire our entire geology graduating class of 20, and in the city of Vancouver alone there were more than 400 mining exploration companies operating at the time. The demand for geologists was extremely high, and we were earning significantly more than engineers graduating at the same time.

I soon learned that there were plenty of summer jobs available for geology students. This was important news, because having a good summer job allowed you to pay for next year’s schooling; also, because these jobs were doing mining exploration in the field, you were building valuable experience for your career. I was offered a summer job with every company with which I applied, so I picked a good one. Phelps Dodge Corporation offered good pay, and they offered me a position on a crew in a remote area of northern BC, which was really attractive to me – I was looking for adventure!

On April 21st, I finished my final exams and headed to the small town of Mission, an hour east of Vancouver. My mother and sisters lived there, and I’d stay there with them until it was time to head north to start my new job. Phelps Dodge had offered me the princely sum of $400 per month. Since they supplied all meals and lodging, my entire paycheck would go straight into the bank. I’d earn enough over the summer months to pay for my entire next year at university and even have some spending money left over. By April 26th, I was working on a construction crew for my Uncle Bob – he was paying me two bucks an hour, and I appreciated the fact that he had offered me employment for the weeks until I started with Phelps Dodge (PD).

By Monday, May 15th, I had moved into Vancouver where PD had put me up in a hotel on an expense account. They were paying the bills, and I savored the moment – I had never even heard of an expense account before that! I spent several days working in a warehouse they leased, getting stuff organized to put on a truck for the 840-mile journey north to Terrace, BC. On the 19th, I took a taxi to the airport and made the 2-hour flight to Terrace. Once arrived, I checked in to the Cedars Motel, where a few of the other guys were already settled.

The next day was spent organizing gear at the Terrace airport, then loading it into a truck which we drove to another camp that PD was setting up about 60 miles to the north near the Nass River. Although we drove all the way back to Terrace late that day, the next day we headed back up with another truckload. We worked hard, building frames for tents that would be used all summer (I’ll show you what those looked like later in the story). After a night at that camp, followed by another day of hard work, two of us drove the 3-ton truck back to Terrace.

A few of us spent our next days organizing gear at a small airport hangar, and making trips to various stores in town to purchase everything from fuel to lumber to food. In our spare time, we drank beer at a nearby pub, went to the movies, went bowling – we actually had quite a bit of free time on our hands. Various bosses for my camp, the Nass River camp and from our Vancouver office were in and out of town making sure that everything kept moving on schedule. The days passed, and we had several weather delays. By fits and starts, we were sneaking in flights to our camp in the Stikine, getting men and equipment up there, but it was slow going. Finally, on May 31st, one of the bosses and I flew north with pilot Ron Wells in a single-engine Otter, arguably the best bush plane ever built. It was a 2 1/2-hour flight in perfect weather. Since the camp was 275 air miles north of Terrace, our average speed was 110 miles per hour – not bad, considering we had a full load. The company which flew us was called Trans Provincial Airlines, which existed until 1979.

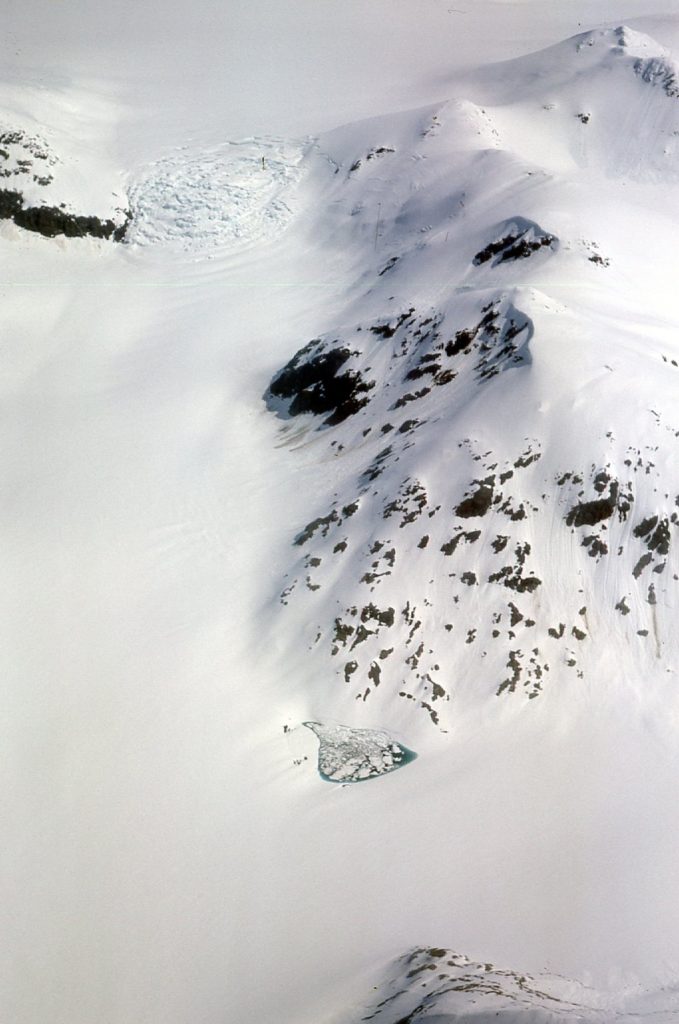

For those of you who have never flown along the Coast Range in northern British Columbia, I have to tell you that the scenery is nothing short of spectacular. I think I’ll let you decide for yourselves, though, as you look through these photos I took that day from the Otter. Here’s one just 10 miles north of Terrace, showing an oxbow lake.

In this next one, we are approaching Kitsumkalum Lake. All of these photos I’m showing you were taken through the side windows of the plane, and some even looking through the windshield and moving propeller.

Here we see the lake, about 15 miles north of Terrace.

Can you imagine my excitement! I was 19 years old, and embarking on an adventure of a lifetime. I would be flying over some of the wildest country anywhere. In fact, once past the Nass River seen in this next photo, we would fly over a full 225 air miles of wilderness with no road, railroad or settlement of any kind.

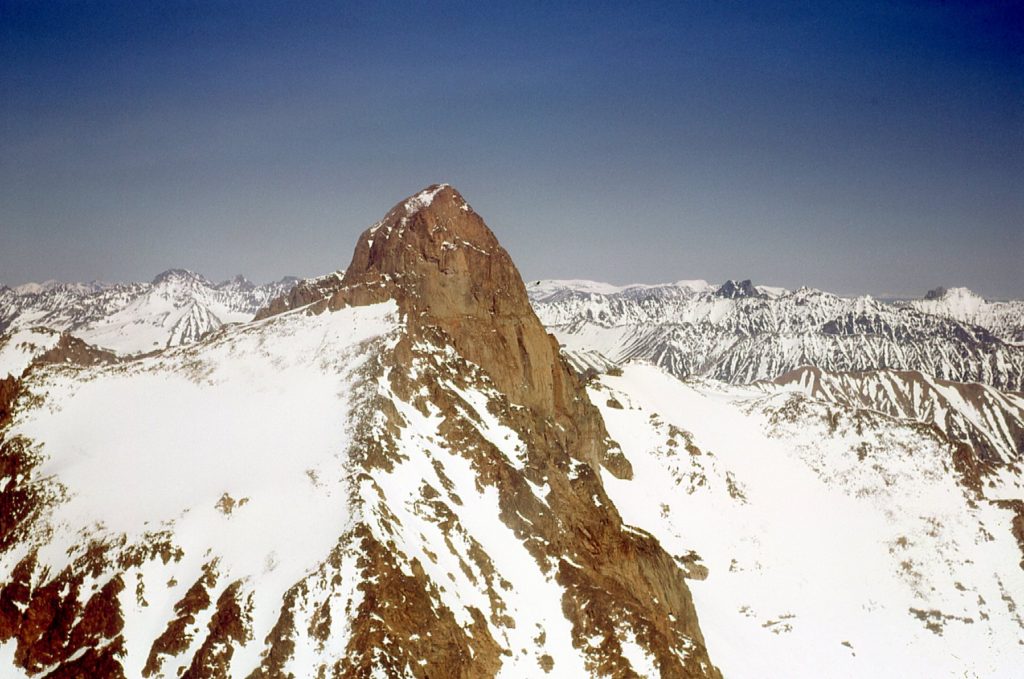

Here’s where it really started to get good.

The farther north we flew, the more wild things became.

I became excited to see the mountains closer to our destination.

So many peaks!

We started to lose elevation.

And kept getting lower.

Still lower.

Finally, we got our first view of Yeheniko Lake, our home for the summer.

I was so excited, I almost peed my pants. We continued to lose elevation, then came straight in at the rudimentary air strip. It wasn’t really much more than a clear stretch. If you look closely at this next photo, you can see a faint orange line on the ground on the left side, meant to guide the pilot to the most open and level area.

We touched down safely and taxied to a stop. Whew! – my first landing in a bush plane – exciting stuff. Here’s a good view of the Otter. Notice the front wheels – they aren’t just wheels, there are also skis on each one, known as ski-wheels. With that arrangement, the plane can land equally well on snow or dirt.

There were already 5 other guys there, and we all set to work to unload the plane. As soon as we were done, the pilot took off for the long return flight to Terrace. Empty, he made it back in an hour and 55 minutes.

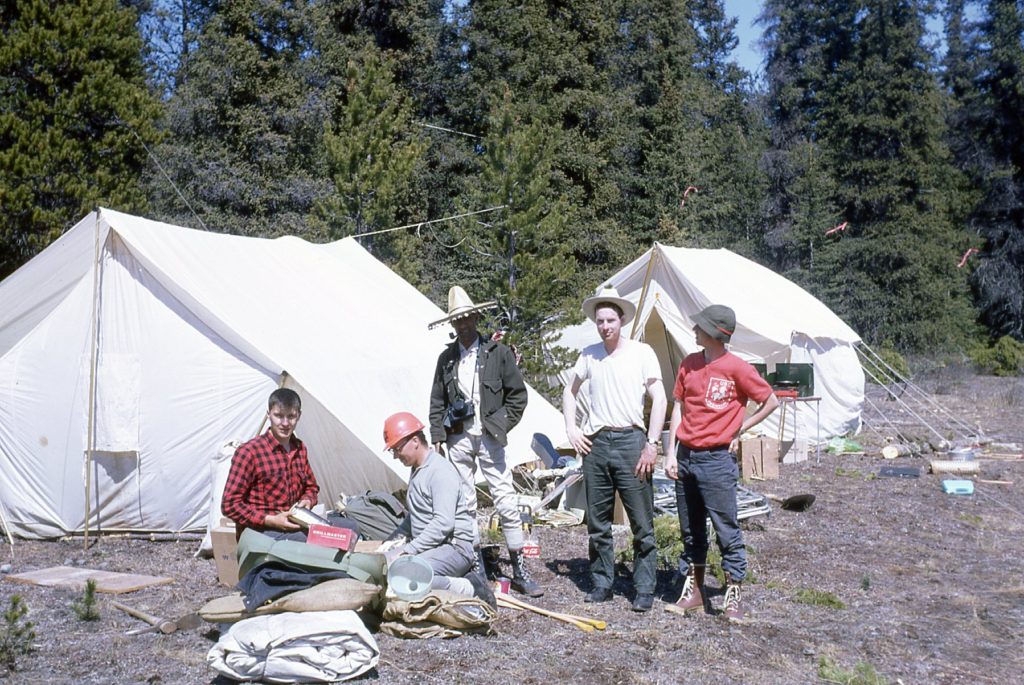

Well, there I was at my home for the summer. Here are the other guys – as you can see, they had already set up a couple of tents temporarily, good enough to use for the time being.

The Otter had brought in a full load, including lumber and plywood for camp construction. During the course of the afternoon, by our combined efforts we set up the first of the permanent tents. Here’s a picture I took at the other camp we had, near the Nass River. It shows how we’d build a frame for the tents.

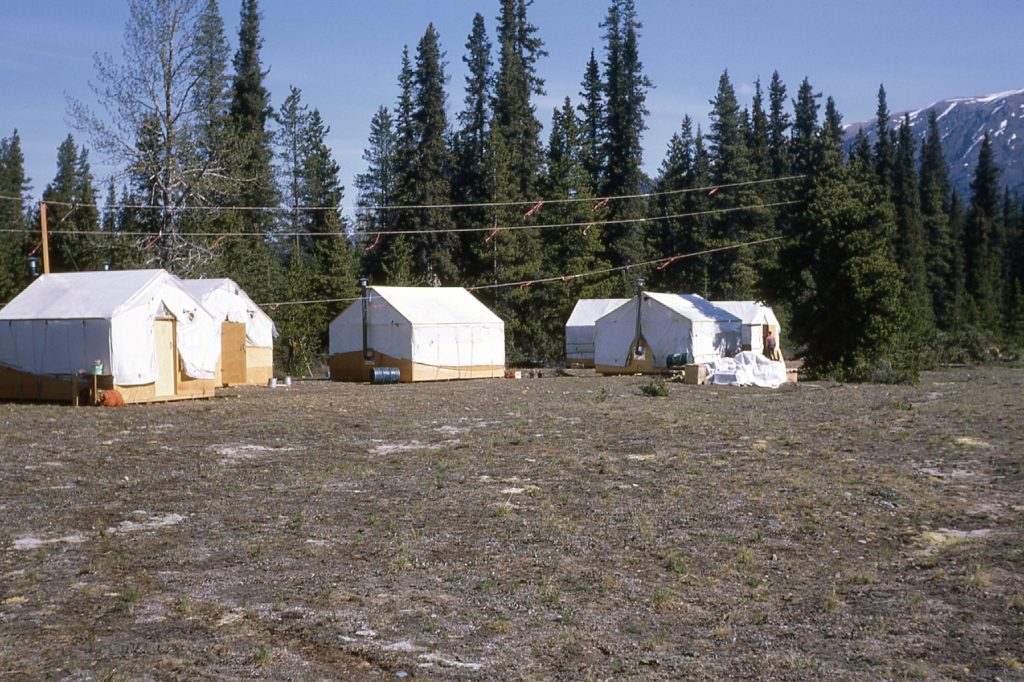

These frames were built to last. On a piece of level ground, we would lay down 4×4 lumber as a base, then a plywood floor. From there, we would use 2x4s to frame walls and a roof. Next would come plywood walls 4 feet high, and even a hinged door made of plywood. With the framing done, we could now stretch a heavy canvas tent over the whole thing, and then a fly to shed rain. In the next picture, you can see our completed camp at Yeheniko Lake, home to 12 men for the summer. These tents were roomy and comfortable. As you can see, each one has a chimney – these are connected to a wood-burning airtight stove inside the tent. Notice the radio aerials we had strung up – these allowed us to communicate with other camps up to 200 miles away.

Even though it was summer, the nights could dip below freezing, so the stoves allowed us to stay warm. One of the tents was the cook tent, where our cook, a seasoned veteran of bush camp life, served up terrific meals. His was the hardest job of all.

On June 1st, a Thursday, my first full day at Yeheniko, the weather was fine. We were all busily engaged in constructing tent frames and making good progress when an accident occurred. I was hammering nails when my hammer hit a glancing blow and ricocheted directly into my face. It was one of those fluky things that was over in a second, but the damage was done. The head of the hammer hit my mouth, mangling my upper lip and breaking off two of my front teeth halfway up. I was working beside one of the other guys who immediately tended to me. It was a bloody mess, but it could have been a lot worse. The edges of the teeth were razor-sharp where they had broken. The boss decided that I needed to get attention right away. Fortunately, the Otter was due back shortly with another load. Once the plane had been unloaded, I caught a ride with the pilot directly back to Terrace. The owner of the charter air service we were using got me an appointment the next day to see a dentist. He ground away the sharp edges on the teeth so at least I could function. In September, once back in Vancouver, a dentist put crowns on both teeth courtesy of Workman’s Compensation and all was well. After another day of recuperation, I caught a ride back to Yeheniko in the Otter and was back to work like nothing had ever happened.

A few words about the man piloting the Otter. His name was Ronald Gladstone Wells, but everyone knew him as Ron Wells. Born in 1911, he was 56 years of age when I knew him. He was a legendary bush pilot known throughout the north. By 1969, he had logged 10,000 hours in the Otter alone, and during his 45-year flying career there weren’t many places in the north he didn’t know. He passed away in 2006 at the ripe old age of 95. I was honored to have flown with him, however briefly, during that summer of 1967.

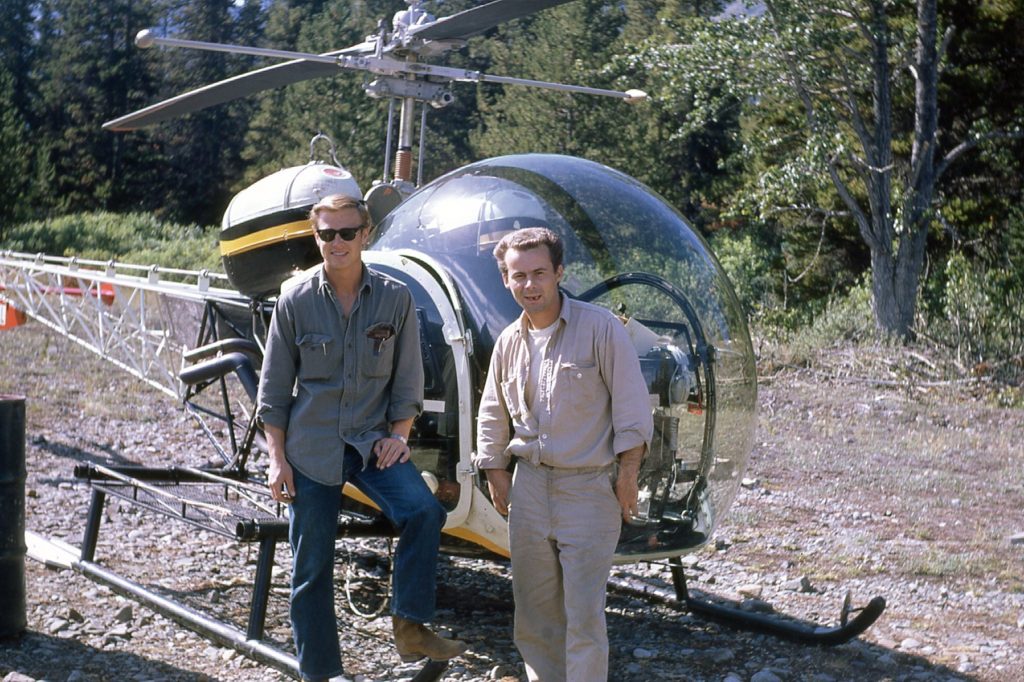

By the time I’d returned to camp, all of the tents were finished. June 4th was a big day – our helicopter arrived. Only the most well-funded exploration projects could afford to have a full-time helicopter, so I had really lucked out by landing a job on this crew. We were now up to our full complement of 12 men: cook, chopper pilot, chopper mechanic, 2 bosses and 7 of us who would be the crew out in the field doing the mining exploration. Here’s a photo of the chopper crew.

Our pilot was a young American guy who was fairly new to the game, while our mechanic was older and had received his training in the military. Since we couldn’t do any exploration by road (there were none), we depended completely on our helicopter to complete our work. If the weather was bad, we couldn’t fly; if the chopper needed maintenance or we were waiting for parts, we couldn’t fly. This resulted in quite a few idle days where we were stuck in camp.

Spare time in camp was spent playing cards or chess, reading, writing letters, or, our favorite activity by far – horseshoes. One of the very first things we did as we set up camp was to build a regulation horseshoe pit – we had all the room in the world for that. Because we were so far north, 57.9 degrees north to be exact, the summer months offered long hours of daylight. Every evening without fail, after supper was cleared away and we’d help the cook clean up, you’d find us all outside at the pit. We’d play for hours. The chopper crew could beat any of us, and it was a rare event if we could defeat either of them – nevertheless, it was great fun. The shoes would fly and the beer would flow. Our cook, Pat Downey, was a confessed alcoholic. However, during the summer months he never touched a drop. His drinking would take place during the non-work months, where he lived in a seedy hotel in a town to the south, a hotel with a pub on the premises. His cooking was second-to-none, though, and no matter what crew I worked on in future camps, nobody could out-cook this guy.

Our pilot, Ron Wells, flew in twice a week to deliver food, fuel and any other supplies. Nothing seemed more important, though, than the mail – it was always eagerly looked-for. Ron said our airstrip was fine for his landings, and also okay for takeoffs with no load, but once the field season was over and he’d have to fly out with full loads as we dismantled camp, the airstrip would have to be lengthened. It was a project we set to right away. It involved cutting down a swath of trees with ax and chain saw, opening up a clear path from the strip we already had down to the lake shore. The 7 of us on the field crew had the job completed after several days of hard work – now, Ron could gun the engine, roar down the strip, fly through the opening in the forest and out over the lake itself. Here’s that beautiful Otter airborne over the camp.

The lake emptied at its north end, where Yeheniko Creek headed north for many miles to empty into the Stikine River itself. We thought that it would be nice if we could create some kind of a bridge over the creek so we could cross to the other side if we wanted. Here’s a view of the creek just a short distance from where it emptied out of the lake.

We found the narrowest spot on the creek and tried to bridge it by felling a tree, but the current was just too swift and swept the tree away.

Once our camp was built and equipped, we got on with the business of mining exploration. It was exciting work, and I’ll tell you all about it in coming stories.