Man, it’s been hot. As I write this, in late August, our temperatures have been running 10 degrees F. and more above normal most days. It feels more like June, typically our hottest month, than August. In fact, we’ve set new all-time records for quite a few individual days lately, and I’ve gotta tell you, it’s getting old. In early June, I arranged to get out of town for a spell, and headed up to our highest mountain range, the White Mountains, to escape the heat.

It’s about 200 highway miles from my place to a town called Show Low, Arizona and it took me the usual 3 1/2 hours to make the trip. It’s mountainous the whole way, so the scenery is great and there’s nothing boring about the drive. My home sits at about 2,200 feet elevation, but by the time you arrive in Show Low you’ve climbed all the way up to 6,600′. I drove a few miles out of town and found my first peak. Porter Mountain is visited by many – a good road goes most of the way up it, and you can park at 7,400 feet. From there, a good viewpoint, you can walk past the locked gate and meander up the road the rest of the way to the summit at 7,595 feet. The top is covered in communications towers, and the soil is volcanic and brick-red.

It was barely one in the afternoon when I was there, so I decided to do one more. Once I was back at my truck, it was a short drive of only a few miles to end up parked in the forest on the north side of Morgan Mountain. An hour later I was on its summit where I signed in to the register with more than 50 previous entries. These little peaks are easy of access and are therefore very popular with peakbaggers. I camped at its base for the night in the quiet piney woods.

I almost forgot to mention that while still in Show Low earlier, I sought and found the high point of the ignominious Ellsworth Hills. This nondescript bump is littered with trash and sits out behind a smoke shop. Some argue there is a contender for the high point on private property a couple of miles away. I visited it too, but who’s to say? It all depends on where you place the boundaries of them thar hills.

The next morning, I drove some miles east, to the village of McNary on the White Mountain Apache Indian Reservation. An excellent dirt road runs from there north to Vernon. I didn’t go quite that far, but instead turned east on lesser dirt roads to park in an obscure spot a few miles later. My goal today was a no-name bump which happened to be the highest point of the Sitgreaves National Forest. Why, you might ask? Well, it happened to be on a list of national forest high-points here in Arizona. It was a pleasant walk through the forest to reach it, where I found no register but signs a-plenty. It was a well-surveyed spot because it also happened to be along the boundary of the Indian reservation.

I’d planned to do another small peak that day, but an unexpected call from home required me to leave early the next morning. Two months passed, and I found myself once again able to head into the high country of the White Mountains.

This time, I drove a Subaru Forester I’d recently purchased – I thought I’d give it a try instead of my old Toyota pickup truck. It wasn’t as roomy, but certainly was more comfortable for all of the driving I’d have to do. It was August 10th when I arrived back in Show Low, and a couple of hours later I’d made my way to the base of Lake Mountain out in the forest. Once again, it was one of those peaks that had a road right to the top, this time because of a forestry lookout rather than communications towers. A locked gate barred the way right at the bottom, so I had to walk the road the 500 vertical feet to the summit. No big deal, though – the road was excellent. Along the way I met Dylan who, it turns out, was also from Tucson. He had already sped to the top and was on his way back down, while I plodded slowly up the road. We chatted for a bit, then went our separate ways. Once I reached the top, this lookout tower greeted me. The fellow manning the lookout tower gave me a wave from high above.

There was a nice cabin there for the use of the lookout guy.

I’d been wondering why it was called Lake Mountain. The map showed an actual depression in the mountaintop, so I decided to check it out. A hundred feet below the cabin and a bit to the east I discovered this.

There actually was a small lake there, an acre in size, if that. It’s out beyond those weeds. Okay, so the name made sense after all. I took a short-cut through the forest to intersect the road lower down and soon found myself back at my vehicle. I had camped at a good spot a few miles away back in June, in a nice clearing at 7,760 feet, and spent another night there. It cooled off quickly and by morning it was all the way down to 50 degrees F., excellent sleeping weather.

The next morning I drove to the nearby Antelope Hills. It was a pleasant walk uphill through the forest to the summit area where I found a register with 36 prior entries. I stayed a bit and then headed back down. This shows you how open the forest was in the area.

I had my eye on a group of higher peaks some miles to the east, over in the highest part of the range. They were all easy, and would allow me to spend my days in even cooler temperatures. An hour later, I found myself parked near the base of Peak 9559. Cows and their calves wandered nearby, gently grazing as I laced up my boots. I was close to the nearby forest which cloaked the upper parts of the mountain. All of a sudden, I heard a mighty crash – what must have been a very large tree had fallen, taking everything else in its path along with it. I’ve felled many a tree in my past, back in my chain-saw days, so I certainly know the sound they make. I didn’t see it, but the crash was unmistakable. Which brings us to the age-old metaphysical question: if a tree falls in the forest and there’s no one there to hear it, did it in fact make a sound at all? Here’s a link which may shed some light on the subject of the possibility of unperceived existence. Undeterred, I headed into the woods and climbed up to the summit. Here’s the meadow where I parked. The crash came from the woods on the other side, but even at that distance it was very loud.

The summit of Peak 9559 was heavily wooded with no view whatsoever. Someone had built a cairn but I found no register.

Once back at my vehicle, I thought I’d check out nearby Greens Peak. It had an obvious road up it, and a lady driving by assured me that it was not only allowed but quite driveable.

The mountaintop was covered with various towers. I didn’t feel guilty about driving up this one, because I felt I’d already earned it. Back in 1992, I had done it the hard way, one evening climbing a thousand feet up the steep power line swath on its north side while on a birding trip (it was worth it, as I saw the blue grouse I sought.)

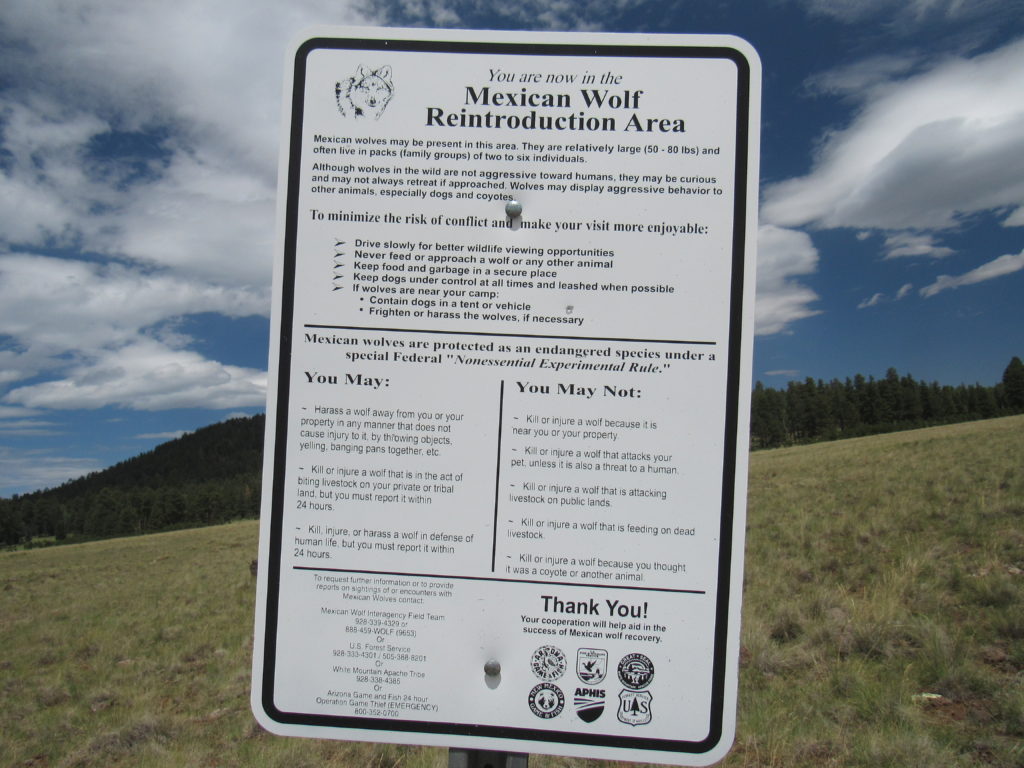

Earlier that day, as I drove into the area, I saw these signs.

I knew that many years ago, there had been implemented a plan to reintroduce the endangered Mexican gray wolf. Since I don’t live in the region where this has been put in place, I never thought much about it. The sign caught my eye, however.

I found a great place to camp, at 9,250 feet elevation. This meadow was right at the edge of the forest and was private and quiet.

When I arose the next morning, the temperature was 45 degrees F – perfect sleeping weather. After I packed up, I drove back out towards the highway, and then it happened. Only a mile north of pavement, something caught my eye off to the left. Running from out of the forest into a clearing came a wolf – I almost soiled myself!! It was grayish-brown in color and about the size of a German shepherd dog. It stopped briefly about 25 feet into the clearing, then turned around and trotted back into the forest, seemingly unconcerned by my vehicle. I later reported the sighting to Arizona Game and Fish Department, which they were glad to receive. It turns out that in Sonora, Mexico about 30 of these wolves survive today; living in the wild in Arizona and New Mexico are a total of 163. It is one of the most imperiled and rarest mammals on the continent. The government has a program in place to reimburse ranchers for any livestock losses due to predation by the wolves – the ranchers don’t much like the wolves, but they have accepted them as part of the natural order of things. I consider myself extremely fortunate to have seen one of these magnificent creatures in the wild.

On today’s agenda was a small peak near the town of Springerville. It was the work of an hour to drive there, where I parked out on an open slope. From this satellite dish, purpose unknown, I followed an old 2-track almost all the way to the top of the high point of the Coyote Hills.

From its summit, I saw something out to the north. I zoomed way in with my telephoto and captured this image. Sitting 28 air miles away and due north was the Coronado Generating Station near the town of St. Johns, Arizona. This coal-fired plant has been polluting northern Arizona skies for decades.

As I walked the mile and a half back to my vehicle, I was accompanied by a show of thunder and lightning nearby. I stopped in town for some fries at Mickey D’s, then headed back up to higher country.

Sitting on the reservation was a tiny community on the shore of Hawley Lake. The 8-mile drive south from the main Highway 260 was really something. It was paved the whole way, but had a posted speed limit of only 25 miles per hour. I thought that seemed awfully low, but once I started driving it I realized why. It was an endless series of curves and switchbacks, dropping your speed to only 20 or even 15 most of the time. Signs at the lake stated that the tourist facilities were closed to tourists due to Covid, but there were dozens of tribal members fishing from the shore or from rowboats – a popular spot indeed. A claim to fame for the lake is this – on July 7th, 1971 the lowest temperature ever recorded in the state of Arizona, at -40 degrees F. or C. (the same in either system of measurement) occurred here. Hawley Lake also holds the distinction of the highest yearly rainfall of any place in Arizona – in 1978, a whopping (for Arizona) total of 58.92 inches. I had always wanted to see the place where these records were set, so now it was done.

I camped in a lovely spot at 9,200 feet accompanied by cows and rain showers, but it was an otherwise uneventful night. It was 48 degrees F. at 6:00 AM when I arose to greet the new day. A short drive brought me to a good parking spot for my first peak of the day. This man-made pond was called Fence Tank and these Angus cattle spent the day here.

Peak 9910, nicknamed “Grassy Top”, lived up to its name. A register sat open to the sky in a cairn of volcanic rocks.

One other thing of note that was easily seen from this peak was the group of high mountains just a few miles to the south. In this next photo, everything you can see out there is on the White Mountain Apache Indian Reservation. The highest-looking uplift just to the right of center is Mount Ord, at 11,357 feet. Look carefully over to the left and you can see ski runs carved out of the forest. The mountaintops above those runs include Mount Baldy, elevation 11,420 feet, which just breaks out above treeline. The ski resort is Arizona’s largest.

There was another nearby mountain I could do. Peak 9947 sat right beside a road and was an easy climb, a good way to finish off the day. It too had no view, the top being heavily treed. I did find a register, though, with 40 prior entries – popular spot!

Another night was spent nearby at 9,200 feet, affording excellent sleeping weather. The next morning, I went to check out nearby Carnero Lake (Spanish for “ram” – were there ever sheep nearby, or did it mean something else?). People were camped around the lake, fishing.

Several miles of driving on good dirt roads took me north and west to finally arrive at the base of Peak 9387. It was wooded all the way to the top but easy going – I never did find a register on the top, so I left one of my own. One curiosity there was this, right alongside the road where I started up. Two strands of the barbed-wire fence ran through this length of PVC pipe – my only guess is that someone wanted to make it easier to step over.

There was something else I wanted to see in the area – Greer. It was a small community in the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest at an elevation of 8,350 feet. It took me an hour to drive there from that last peak, and I was glad I went. I thought it would be a regular town, but I was surprised to see that it was a series of cabins, lodges and the like all stretched out for a few miles along one road in a valley bottom. Hardly anyone actually lives there year round, fewer than a hundred, but the facilities there could support many hundreds more. The day I was there, it was bustling with tourists. They were lined up waiting for a seat at the few restaurants, and there were plenty of others fishing. It must be a center for outdoor activities – fishing, hunting and the like – and of course the nearby ski hill. Greer sits only 11 miles from the source of the Little Colorado River, a major tributary of the Colorado River in Arizona. Click on this link to read about this fascinating river. It’s still pretty small as it passes by the town.

Both sides of the one street through the town have many lodges, resorts and cabins like these.

So there, I’d finally had a look at Greer, Arizona. My curiosity satisfied, I drove back out to the highway. There, staring me in the face was something called Antelope Mountain. My map showed a road going over to it and all the way to the top. Hmmm, it was worth a look. In this photo, you can see the road heading up the mountain.

I made my way over to the base of the peak, then started to drive up. The road was pretty good all the way up to the 8,700-foot mark, then it went to hell in a hand-basket. The surface became very rough, with a lot of jagged rock and several steps to negotiate. I was driving a Subaru Forester and was in genuine fear of smashing the undercarriage. I put it into what they called symmetrical all-wheel drive, and somehow managed to make it all the way to the top with no damage. The summit was 9,003 feet elevation. About 60 feet lower on a small knoll were some sorry-looking antennas atop a framework of telephone poles, seen here.

After a short stay, I slowly made my way back down over the rough spots to the valley bottom. One more thing I wanted to show you – these aluminum fences. They are called snowdrift fences, and are meant to create turbulence, causing the blowing snow to pile up between the fences and the roadway, thus helping keep the roads more free from snow in the winter. Most of these are found at or near the 9,100-foot level along the highways.

After one more night spent camped at my favorite 9,200-foot campsite (yes, by now I had favorites), I made the drive home. Six days had yielded 10 peaks – that was good, but even better was getting out of the heat for a while.