The Devil’s Road. The very name conjures up all kinds of images, none of them good. It is a track through Arizona’s deserts which nowadays runs from Ajo to Yuma, approximately 130 miles. The original path wasn’t exactly as we know it today. Here’s a sign which greets travelers and tells something of its history. It’s a bit hard to read in this old photo, so I’m going to spell out for you what it says.

“The Road of the Devil” is a rough, unpaved route which begins in Altar and Caborca, Mexico and crosses southwestern Arizona, ending in Yuma. Prehistoric peoples used the route to transport shells and salt from the Gulf of California. Spanish soldiers led by Melchior Diaz in 1540 were the first Europeans to travel this route. More than 150 years later, the Jesuit priest Father Kino traveled the region while exploring for routes to California. After the discovery of gold in California in 1849, thousands traveled the Camino in search of gold and new lives. Historians estimate more than 400 people died of thirst on the Camino in the 1850s. At one time, at least 50 graves could be identified along the route. Today the area (part of which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places) is under restoration. Please stay on the road and help us protect this historic resource.”

That tells you a bit about the road, and should be enough to whet the appetite of any history buff and adventurer. I’ve had the good fortune to have visited the southwestern corner of the state many times since my first trip out there in 1987. I’ve been there alone and also with friends, and every visit reaffirms my conviction that this is indeed my favorite part of Arizona. As many times as I’ve traveled the road, there were a few tiny bits that I hadn’t seen, so when Jake suggested that we drive the full route from one end to the other, I was immediately on board. We had 2 full days and a bit of a 3rd to make the trip, and figured it would allow us to at least see the major points of interest.

It was around seven in the morning when Jake picked me up. Tucson had just experienced one of its rare snowfalls, seen here in my neighborhood.

As we headed out of Tucson, all of the higher mountains along the route were white with snow. A couple of hours later, we arrived in the town of Ajo where we gassed up – you don’t want to run out of gas out on the Camino. A couple of miles south of town, we turned off the paved highway and started our adventure. The elevation was 1,714 feet, and the road there is wide and level. Straight ahead was Black Mountain, the high point of the Little Ajo Mountains. That big thing on the right side is part of the tailings pile from the open pit New Cornelia Mine, now closed these many years.

It only takes a couple of miles before the road narrows and gets a bit rougher. We pass a site known as Darby Wells. The O’odham people, the Native Americans who have traditionally populated Arizona’s desert southwest, comprise 3 different groups. One of them is known as the Hia C-ed O’odham. It is felt that they number about 1,000 but they have no land they can call home. Instead, they are widely scattered in communities like Ajo, Tucson and Phoenix. Tucson receives about 11 inches of rainfall a year and Phoenix gets 6. The Hia C-ed lived in an area bounded by the Ajo Range on the east, the Gila River on the north, the Colorado River on the west and the Gulf of California on the south. They were known as the Sand Dune People and their ancestral land was the harshest of all, receiving on average 3 inches of rainfall each year. They were a hunter-gatherer people and nomadic, having no villages to call home. They caught jackrabbits by chasing them down in the sand; they hunted bighorn sheep, mule deer and pronghorn antelope with bows and arrows. They caught muskrats and lizards, and sometimes went to the gulf to fish and gather salt. They also ate plants such as edible flowers, mesquite beans, saguaro fruit and pitaya.

Theirs must have been the harshest, the most challenging, existence of all. Most of the lands they inhabited were taken over by various government entities such as Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge and the Barry M. Goldwater Air Force Range. The U.S. government has never recognized them as a separate tribe. By 1900, they had mostly left their ancestral lands and intermarried with other O’odham and moved to towns such as Ajo, Gila Bend and Phoenix for work. I think it’s sad to think how a culture could lose so much of its identity in that way. The area around Darby Wells is where some of them lived before moving on.

Around 6 miles into our journey, we can see Locomotive Rock off to the west.

We are passing through BLM land these last miles (Bureau of Land Management). Off to the west is the small range curiously known as the John the Baptist Mountains. They were named for John C. Butala, a hermit who had a cabin on the east side of the range and died in 1961. They say he was likely nicknamed John the Baptist because of puns on his name or his appearance as a wild-eyed, ascetic prophet.

Our road through these miles is commonly referred to as the Bates Well Road, and we are actually traveling through what is known as the Valley of the Ajo. Off to the southwest, we get a good view of a couple of peaks. On the left is Peak 2141, the long broken ridge; the big one on the right is Scarface Mountain. There’s an airy ramp near the summit of 2141 which is fun.

Near the 13-mile mark, we come to the entrance of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Established in 1937, the monument covers 330,000 acres of land and shares a 30-mile-long border with the Mexican state of Sonora. It serves to protect most of the specimens of the organ pipe cactus found inside the USA, and most of the specimens of the senita cactus found inside the USA, and is an International Biosphere Reserve. A road heads east along this northern edge of the monument, referred to as “The Pipe” by the Border Patrol. We were surprised to see this heavy equipment sitting there.

The young grader operator was taking a nap as we pulled up.

The road they were working on runs east for about 10 miles to Highway 86, and is used only by the Border Patrol. There were signs that told about the Pipe.

We didn’t have to pay an entry fee because I have a lifetime senior pass.

We motored on, and soon came to this sign. Someone had painted the words “O’odham Land” across it. It’s true, this was all part of their ancestral land before we took it away.

We soon came to this tower. It and others like it are put up by the Border Patrol. A solar panel powers an emergency signal.

The wording on the sign was much faded, but it says, in 3 languages, the following:

If you need help, push red button. US Border Patrol will arrive in 1 hour. Do not leave this location.

Nearby was this blue flag flying atop a tall pole.

On the ground was this blue barrel. The government allows a samaritan organization to place these barrels of water to help out people dying in the desert.

At around 17 miles into our journey, we arrived at Bates Well. There is a windmill, small ranch house, corrals and a line shack here at the north end of the Bates Mountains. The well was hand-dug by W.B. Bates around 1886 and passed through a succession of owners including Ruben Daniels, the McDaniels brothers and Henry Gray. Some Hia C-ed O’odham claim that the name of this important settlement refers to burnt seeds tossed on the ground while organ pipe cactus jam is being made; others interpret it as “saguaro seed cakes”. Their historic name for the place was Tjunikáatto, meaning “where there are dry cactus fruit seeds thick on the ground”.

Barely 4 air miles to the south sits Kino Peak. This beauty is tricky, and repulses fully half of those who attempt it. The route climbs the shaded face on the right side, and is a solid Class 3. It’s not the grade, but the route-finding that stumps many who try it. Its first ascent was completed by my friend Barbara Lilley and a group from California back on February 17th of 1952. Many who attempt it in the winter from Bates Well will start in the dark and finish in the dark.

From Bates Well, you get this better view of Scarface Mountain, sitting off to the north.

Off to the northwest of Bates Well sit these 2 peaks. The one on the left is Peak 2230, guarded by a lot of steep, loose rock. To the right of it is the taller Bates Benchmark. This one was exciting for me. Late in the afternoon of the day before I climbed it back in 2015, a Border Patrol chopper kept circling the summit, flushing a couple of scouts working for one of the drug cartels. When I went to the top the next morning at daybreak, I was pretty nervous. Luckily, the Bad Guys had left by the time I got there.

Only a couple of miles west of Bates Well, we entered the wide expanse of the Growler Valley. On its east side sit the Growler Mountains, a long range quite over-run by drug cartel lookouts. The range presents this dramatic escarpment, dropping 1,500 vertical feet to the valley below.

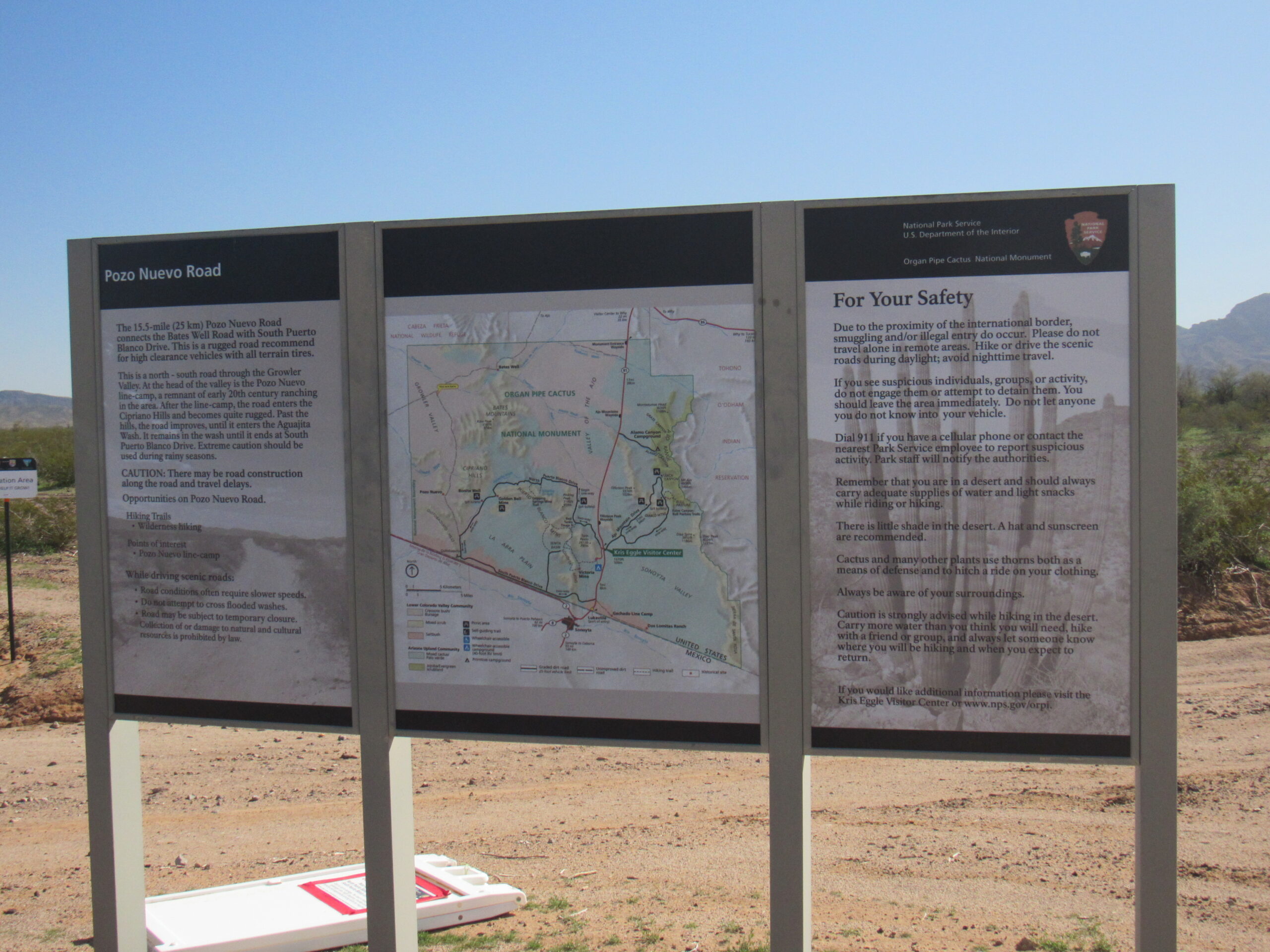

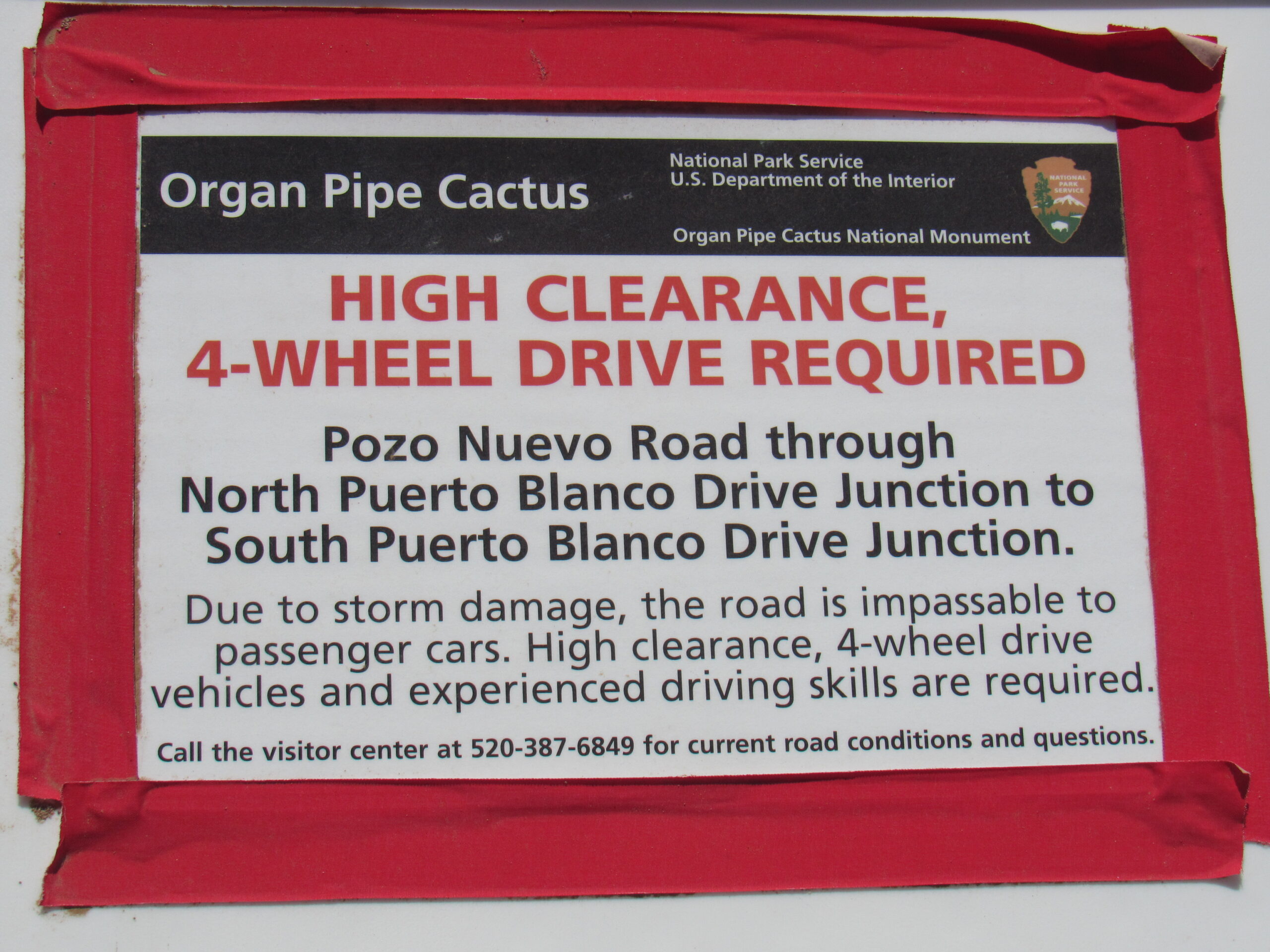

At around 23 miles into our journey along the Camino, we arrive at a road that heads south. This is the Pozo Nuevo Road. Not a lot of people travel this 15-mile-long road these days – it has always been rough, but it’s even worse nowadays.

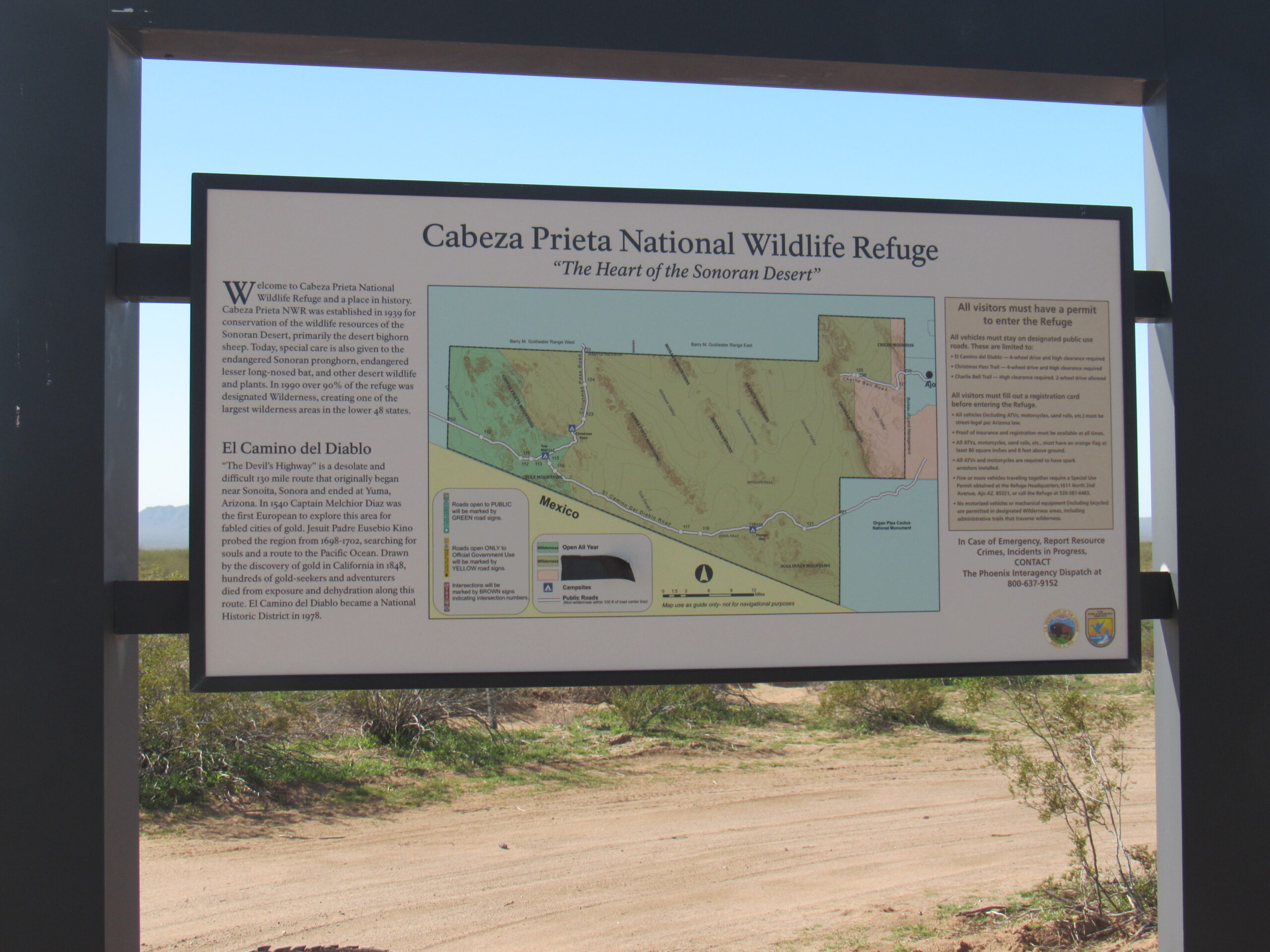

The Camino continues west, and at around 26 miles, we leave Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and enter the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge. Up to this point, we have traveled through 13 miles of BLM land and 13 miles of OPC land. As we enter the CPNWR, we are greeted by these signs.

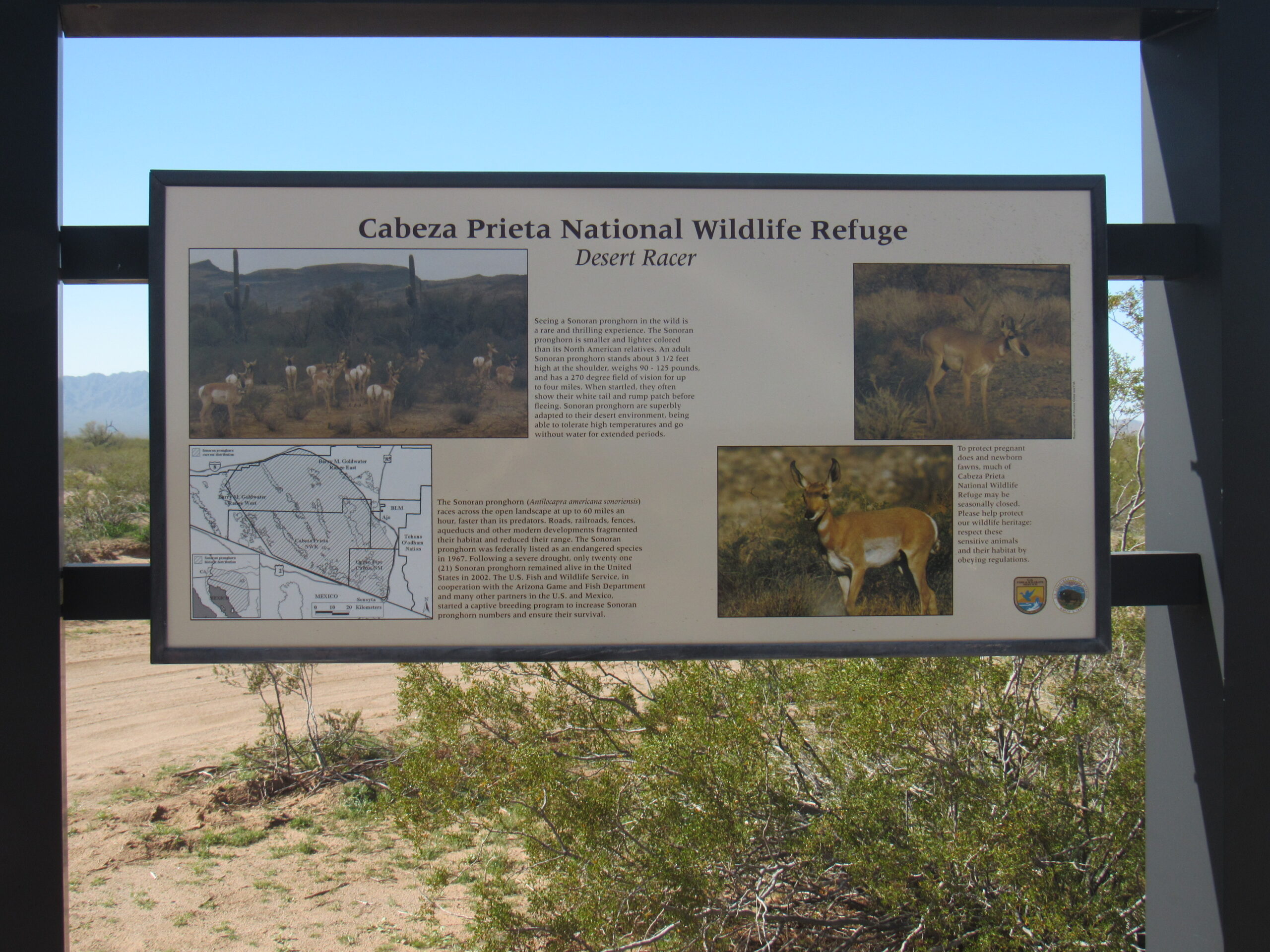

This sign talks about one of the rarest mammals in the world, the endangered Sonoran Pronghorn Antelope. In 2002, their numbers in the US had dwindled down to only 21. I have been very fortunate to have seen them 4 different times – Jake still awaits his first sighting.

The Cabeza covers a vast 803,000 acres of designated wilderness area, and is a truly amazing place. Not a single human lives within its boundaries. It shares a 56-mile border with the Mexican state of Sonora. You can read more about the refuge here. Near the boundary with Organ Pipe sits this Border Patrol station, referred to as Boundary Camp. Agents come here on a one-week rotation.

The tall tower has a device that can detect movement at a distance, and can look in any direction. Ten years ago, Jake and I approached it from a remote spot 8 miles away and they spotted us and watched us while we approached, and we thought we were being so stealthy!

I’m going to sign off for now and resume our journey in Part Two, so please stay tuned.