All peakbaggers, and I’d even go so far as to say all mountain climbers, have lists of peaks they’d like to climb. Hell, even rock climbers have lists. Some of these lists are short and easy, some are lengthy and near-impossible, especially if you adhere strictly to the list and climb everything on it, no exceptions. So when it comes to being a list-driven climber, well, I’m guilty as charged. Back in the 1980s, I became really curious about how many mountain ranges there were in Arizona. Try as I might, I couldn’t find any list of them. It seemed like a simple enough thing, really. I mean, how hard could it be? All you’d have to do is sit down and look at some maps, right, and the names of the ranges should just jump out at you and then you’d write them down, right? Well, since there didn’t seem to be any list out there, I decided I’d have to make my own.

Where to begin? I only had a few of the topographic map sheets for Arizona, so I phoned around and found out that the local university had a fabulous map collection. In fact, they had a complete set of all the maps, covering every square inch of the state. Once I got there, it felt like I had died and gone to heaven. All beautifully organized, they were there to enjoy at my leisure in air-conditioned comfort. I had no idea what an undertaking this would turn out to be, though. The days turned into weeks as I pored over the more-than-1,800 maps for Arizona. Once I’d started looking, I had decided that I’d do it right the first time or not at all. Anyway, to make a long story even longer, by the time all was said and done, I’d found 193 different mountain ranges in the state. Since the whole idea was to make a climbing project out of all this effort, I then set out to identify the highest point of each range. Finally, the list was made and now all I had to do was climb all of them. That took another four years, but that’s another story.

As I worked my way through the peaks on the list, I realized that there were a couple that would prove more challenging. Once my friend Lars led me up Baboquivari Peak and that one was out of the way, I only knew of one other (okay, maybe two) that were technical in nature. The high point of the Eagletail Mountains was keeping me up at night, so I lucked out when I learned that a fellow I knew, name of John, had already climbed it and agreed to go back and lead me up it. Legendary peakbaggers Barbara Lilley and Gordon MacLeod wanted a crack at it too, and John was okay with that – he’d do his best to get all of us to the top.

The big day came – November 19, 1989. The three of us met John some miles east of the range, then convoyed west and finally parked out in the desert where the road ended. We got our packs ready, then followed him across the desert from our starting point of around 1,200 feet elevation. The ground rose steadily as we headed southwest, finally reaching a saddle at about 2,500′ after two miles. The main spine of the Eagletail Mountains runs from the northwest to the southeast. We now made a left turn and followed the ridge for a mile and a half, crossing over five intervening bumps, to arrive at the base of a steep 250′ gully. This was climbed, to put us almost at the summit.

The highest part of the mountain has three rocky towers which can be seen from a great distance. These are the “feathers” on the eagle’s tail. All three of them, the south, middle and north are technical rock climbs, with the north being the highest. We had arrived at a spot which was at the base of the north feather, the place where the climb to the summit would begin. John had been in a bad mood all day, both before and during the climb. Since there was no good place to camp for the night, Barbara and Gordon turned around almost immediately. John shouted to them that they’d better be back to this very spot at sunrise, or the climb was off. They promised they would, and down the gully they went. This showed me two things about them. The first was that they were made of stern stuff – they had just climbed over 2,000 vertical feet, were turning around and descending the same amount, and would climb it all over again in the dark a few hours later. The second was that they loved car-camping. I’ve car-camped with them, and I can attest that they do it in style, like nobody else, in their Suburban. So they had a comfortable night, albeit a short one.

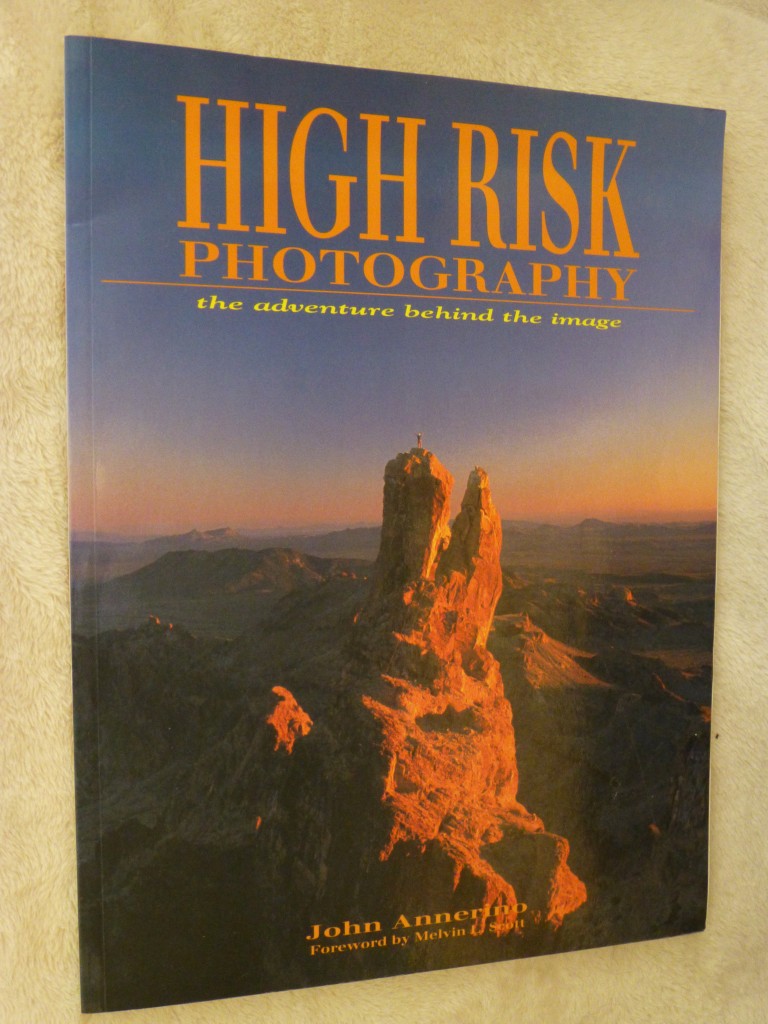

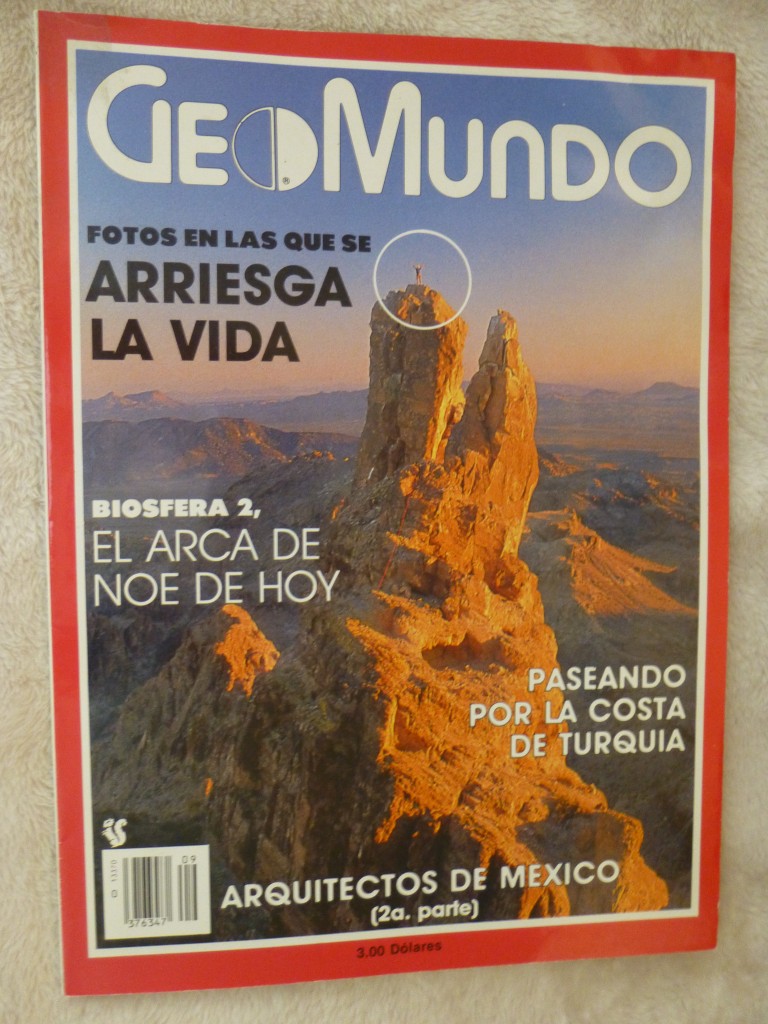

Meanwhile, John and I roped up and headed carefully over to the south feather. He led us up to the top, one pitch of 5.0, where I tied in. This was an exposed spot, to put it mildly, the summit platform being about 3 feet by 3 feet. John went back down, then over to our bivi site by the north feather, where he set up his camera gear. He wanted me to pose on the top around sunset, “magic hour”, to try and get a photo he had been dreaming of. He had even given me a railroad flare, which I was to light and hold aloft for some of the pictures, and that I did. He took about a hundred shots on 35 MM film, and I think he got the one he was looking for. In fact, the picture was so good it made him famous.

Once the photo session was over, I downclimbed the pinnacle and made my way back over to our bivi site. Truth be told, it was tiny. We spent quite a while piling up rocks to create a spot big enough for two sleeping bags. John was in a crappy mood, and didn’t say two words to me, instead turning in as the last light faded. I really hoped that by morning, he’d smarten up and be in a better mood.

At first light, we prepared for our climb of the north feather – the start was only 30 feet away from where we’d slept. A bit of noise below told us that Barbara and Gordon were climbing to our position, and then they were there. As promised, they had re-climbed the 2,000-plus feet in the dark to make it back up by sunrise. Amazing. At the time, Barbara was about 60 and Gordon, 65.

John and I roped up. He quickly led the 60-foot pitch, a stiff class 5.6 with enough exposure to satisfy anybody. I followed, cleaning the route, except for one piece of pro, or maybe there were two, that, try as I might, I just couldn’t retrieve. That didn’t improve his mood any. I tied in for safety on the narrow summit of Eagletail Peak, elevation 3,300′, and sat back for the ride while John got things ready for the others to climb.

Barbara had decided to not climb John’s ascent route. Instead, he set up a doubled rope and tossed the ends down to her, and she attached a pair of jumars. Standing in the webbing she had on the jumars, she was able to inch her way slowly up the ropes. Much of the distance was overhanging, so it required a huge amount of effort on Barbara’s part to climb the rope. It was hard to not spin as she hung several feet out from the east side of the cliff. As I recall, it took well over an hour for her to make it to the top, where John and I helped her over the lip. She was totally spent. Gordon had had lots of time to watch these proceedings, and by the time Barbara stood on the summit, he had thrown in the towel. He declared that there was no way he’d even attempt it. So ended our climb.

Using the same rope, all three of us rappeled of the summit to where Gordon waited. John hurriedly packed up his gear, and, without a word to anyone, started quickly down the steep gully. We were astonished to see him take off like that. Barbara asked me where he was going in such a hurry, that she at least wanted to thank him for all his help. I shouted down the gully after him, but he didn’t even bother to respond.

I too packed up my gear, then told Barbara and Gordon that I’d catch him up and see what his problem was. He had been in a pissy mood all day, seeming to get more annoyed as the hours passed. Promising to meet up with them on the morrow, I set out down the steep mountainside in a hurry. I knew I’d have my work cut out for me, as John was a renowned long-distance runner. He had at least a ten-minute head start on me, so I didn’t exactly stroll down the ridge. A couple of miles later, we were both down off the ridge when I caught up to him. “What the hell is going on?”, I asked him. He mumbled something about having a bad day, and I flat out told him that his behavior had been beyond rude, to say the least. He still wasn’t in the mood to talk about it, so I pulled ahead of him and left him in my dust, arriving at the trucks a full ten minutes ahead of him. I didn’t stick around to wait for him.

Motoring on, I covered 150 hard desert miles before stopping for the night. After a good night’s sleep, I met up with Barbara and Gordon at an agreed-upon location, then we drove the last miles to a little-known range called the Tank Mountains. They had been there at least once before, attempting to climb the range high point but getting turned back near the top. They figured the three of us could mount a more concerted assault on the thing. So, we did, climbing up the 1,000 vertical feet to the crux, where we roped up. They had me lead, not sure why, and before you know it, we stood on top of Peak 2506. It was pretty quick, really, rated as Class 5.2, and It appeared to be a first ascent. This range was really off everyone’s radar, but news of our climb spread to the usual suspects, and it has seen at least half a dozen ascents since ours.

It had been a worthy trip, with two range highpoints under our belts. I was relieved to have them done, and to this day still have fond memories of them both, especially of the quality time spent with Barbara and Gordon.

Please visit our Facebook page at: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690