Each year in March, I have a week off of work because our schools are closed for what they call Spring Break. It’s a time when I plan something special, a longer outing to do some climbing where just one or two days wouldn’t suffice. Since all of my other climber friends had their own agendas, it looked like it would be just me this time. I had a full 9 days if I needed them, so I planned and packed for the entire time. By 12:30 PM on the Friday, I hugged my wife goodbye and drove away. If I had known the type of adventures I was about to have, I would have hugged her twice as hard.

Two hundred easy miles of freeway driving brought me to the town of Wellton, Arizona where my main mission was to fill my gas tank to the brim. There’d be no gas stations where I was headed, and as deep as I was planning to go into the desert, I had to be absolutely certain that I could get all the way back out again. That might not sound like such a big deal, but trust me – it is. Running out of gas in the desert could cost you your life.

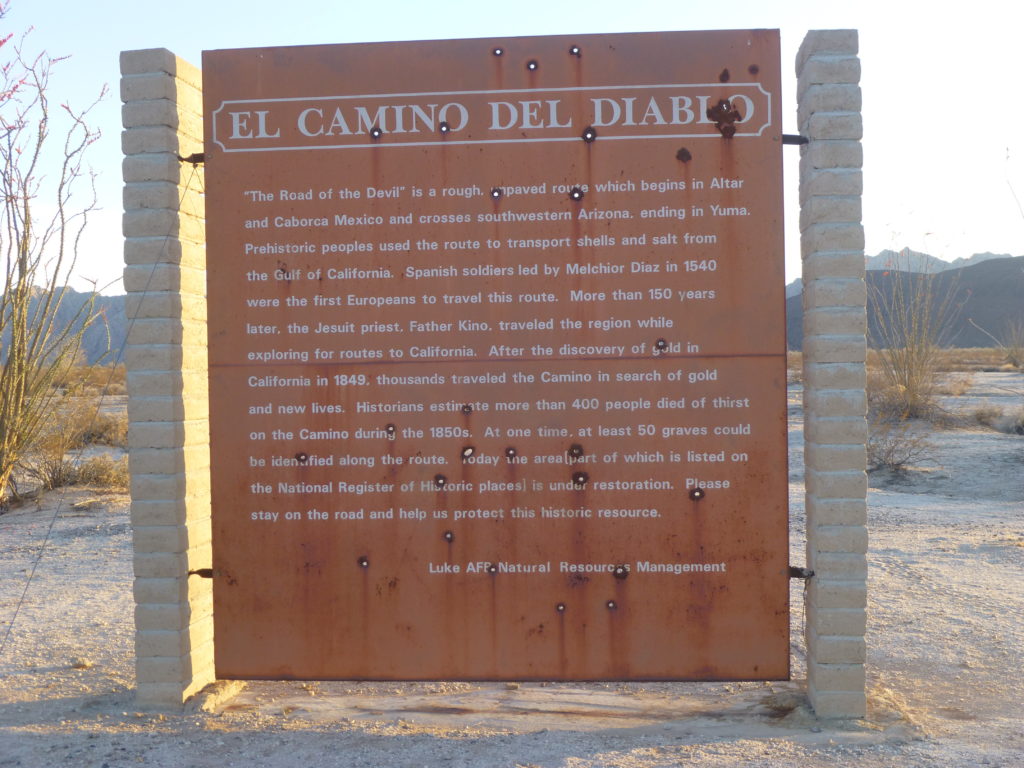

Once I passed the last golf course on the southern edge of town and turned on to the dirt road known as the Camino del Diablo, this was the first sign that greeted me.

Here is a short Wikipedia description of the Camino.

“El Camino del Diablo (Spanish, meaning “The Devil’s Highway”) is a historic 250-mile (400 km) road that currently extends through some of the most remote and arid terrain of the Sonoran Desert in Pima County and Yuma County, Arizona. In use for at least 1,000 years, El Camino del Diablo is believed to have started as a series of footpaths used by desert-dwelling Native Americans. From the 16th to the 19th centuries, the road was used extensively by conquistadores, explorers, missionaries, settlers, miners, and cartographers. Use of the trail declined sharply after the railroad reached Yuma in 1870. In recognition of its historic significance, El Camino del Diablo was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. It has also been listed as a Bureau of Land Management Back Country Byway. The name, like its other historic name Camino del Muerto, (“road of the dead”) refers to the harsh, unforgiving conditions on the trail.”

The road was a good one, wide and well-traveled. Marines from the Marine Corps Air Station in Yuma use it constantly, and the public is allowed to use it also (once you have obtained the proper permit). If you don’t mind a few bumps, you could probably do 50 mph along it.

There was a small peak I was hoping to do this first afternoon, and a few miles of travel along a side road took me right to it. Peak 1225 was an insignificant bump compared to others nearby which towered 2,000 feet above it, but it was on a list of mountains I hoped to climb on this trip and so there I was. At 5:20 PM I had this view from its summit, looking southeast across the Lechuguilla Desert.

Once back at the truck, I made my way back over to the Camino and continued south. The military has a real presence in this area – I passed a fenced area with dozens of their vehicles parked here.

In fact, there was such a military presence out here that every few miles I could see a few buildings or a radio tower. And curiously, from time to time I’d pass something like this. Porta-potties, because when you’ve gotta go, you’ve gotta go, right?

A few years ago, in another area used by the military, I saw some toilets like these but from a different company. The phone number on them was 1-800-GO1AND2. You’ve got to hand it to these toilet rental companies, they have a good sense of humor.

I managed another dozen miles before the light failed me and I pulled off the road to camp in a flat, quiet spot a mere 8 miles from the Mexican border. Today had been a good start, but tomorrow would see me on the biggest mountains of my trip – I was keeping my fingers crossed that all would go well.

An early alarm saw me packed and driving while it was still dark. First light came at 6:30, and soon after that I drove a last few miles up a valley into the heart of the range. I was in the Tinajas Altas Mountains, which means “High Tanks” in Spanish. The range is named after a series of natural water catchments which are found one above the other on the eastern side of the range, only 3 miles from Mexico. Here is a brief description of the tanks from Wikipedia:

“The historic campground at Tinajas Altas (“high tanks”) features nine cup-like pools (tinajas) perched one above the other on a steep granite slope, that are replenished solely by rainwater. When full, these tinajas may hold up to 20,000 U.S. gallons (76,000 L), but due to the lack of rainfall and arid atmosphere, one or more are frequently empty. In the days before motor vehicle transport, some travelers perished after finding one or more pools dry. During the 1891-1896 U.S. Boundary Survey expedition, the surveying party related the story of three dead prospectors found just above the empty first tank. The men’s fingers were worn raw from climbing the rock to the second tank, which held water, and it was apparent the men had died just yards from their salvation.”

The valley I drove into is only a mile south of the famous tinajas, and it was an easy drive to reach its end and park. I was perfectly positioned to climb 3 big peaks here which appeared untouched, and it was with guarded optimism that I walked away from my old Toyota pickup at 7:30 AM. The sun still hadn’t penetrated very deeply into the canyon in which I climbed.

The canyon twisted and turned, and where it was heading kept me guessing. At one point, I had this glimpse into higher country – from this view, I still couldn’t tell where my peak was.

After a couple of hundred feet of climbing, I rounded a corner and came face to face with this – we call it a waterfall. Although there’s no water falling down it 99.99% of the time, this one is smooth rock and spanned the canyon from wall to wall. Sometimes you can try to climb straight up the thing, or climb around it on the side. The latter choice was the one I made.

On top of the waterfall, I was surprised to find this concrete dam. These are created to impound water for animals to drink, to allow them to survive in this harshest of environments.

And to ensure that the dam won’t fill with sediment and become useless, this barrier was built above it to prolong its life.

If you click on this link, it will open a topographic map centered on this spot. Zoom in. See the tiny blue dot? That’s there to indicate the dam. It would be easy to miss, wouldn’t it?

https://listsofjohn.com/qmap?lat=32.2850&lon=-114.0514&z=12&t=u&P=300&M=Desert+Mountaineer

Beyond the dam, I had to choose among several canyons in order to continue. It appears that I picked the right one, because a while later I reached a more level spot, from which I had this view looking up the final 300 feet to what I assumed was the summit.

So far, so good. This last stretch steepened towards the top, but it went well and 2 hours after setting out I stood on top of Peak 2399. Man, this was a steep spot – everything dropped off dramatically on all sides. There was no trace of any previous visit, so I built a cairn and left a register. The views were outrageous. Here’s one to the southeast, to the highest point in the entire range, a mere 3,500 feet away – it’s along the ridge to the right of what appears to be the highest point.

Looking west to the border, I’ll point out a few details in this next photo. See the dark line running diagonally across the upper part of the photo? – that’s the big metal vehicle barrier along the border itself.

Here’s a close-up of a small bit of the barrier – see how there’s a gap at the hill in its path? That’s because that bit is too steep for vehicles to drive over, so they don’t go to the trouble to extend the barrier over the hill. Look in the extreme upper left of the photo – see the grey line? – that is Mexican Highway 2.

After about 15 minutes on top, I packed up and started down. It was steep and I took my time – by the time I was back at the truck, almost 4 hours had passed. That had gone well, and I was feeling pretty stoked. There were still 8 hours of daylight left to me, and that seemed like it’d be plenty of time to do the other 2 peaks nearby. I ate some lunch, then set out due west for the next one.

The first peak had required almost 1,400 feet of climbing; this next one was 150 feet lower, so hopefully would go even more quickly. The summit was less than a mile distant – I could see the whole east side, and thought I could see a route all the way to the top. In no time at all, I was clambering up a bowl on the northeast side, but the higher I got the steeper it became. I reached a point where the slope was nothing more than dirt with a few rocks sticking out of it – what an ordeal, two steps up and then sliding down one. I was forced farther north, and by the time I reached firmer ground, my nerves were really jangled. A bit more work brought me all the way over to the north ridge, where my jaw dropped. I had been hoping for a straightforward finish, a decent route to the top – it was anything but. What confronted me was a route bulging with rounded granite, steep and horribly exposed. I estimate I was at least 125 vertical feet below the summit. I took one look and immediately decided that there was no way I was going to try that alone. Here is what I was seeing.

What you see in this next photo is the terrain immediately to the left of that in the above photo. You can see the steep ground leading up to the summit on the right side – that’s what I had avoided earlier, ending up on the ridge instead. See the big peak on the horizon in the middle? – that’s the one I’d climbed earlier, but from the other side, out of sight. And that’s the range high point over the ridge on the far left poking up into the sky.

As I sat there, huddled on the ridge on a bit of a flat spot, I felt really disappointed with myself – I felt I had failed. All that work for nothing. After a few minutes there, with a few pictures taken, I started back down the way I’d come up. It was a slow, careful process, at times down-climbing by facing inwards. By the time I’d reached the level ground of the valley floor, more than 3 hours had passed with a thousand feet of climbing under my belt. No summit, but plenty of excitement. This peak had put the fear of God into me, and I knew it would affect the rest of my trip. In spite of that, I recalled the adage that many of us climbers use: there are old climbers and there are bold climbers, but there are no old, bold climbers. I hope I’d made a good decision – actually, I believe I had. It’s better to come back again another day, to pick a different route, to climb with a partner – the mountain will always be there.

The third peak of the three I wanted to climb in the valley – well, now being a bit gun-shy from my recent efforts, I took a good look at it and decided to not even try it. It’s the pointed one right in the center.

It was time to move on. As I drove east and out of the valley, there were many impressive peaks along my path, like these.

Once back out of my valley, I headed north on poor roads. My route took me right past the entrance to the High Tanks, but I motored on. Little did I know it, but within an hour or so of my passing, climber friend Andy Bates and his family had visited the tanks. A slight deviation and we would have met up, quite unexpectedly, way out there hundreds of miles from our homes. It had been quite a day – some success, some disappointment, but it was time to move on to new horizons.

Stay tuned for the next part of the story, entitled “The Yuma Desert”.