The 3rd-highest peak in North America is commonly known as Pico de Orizaba, but many would argue its proper name is Citlaltépetl, from the Nahuatl words meaning Star Mountain. Mexico’s highest peak, it is only exceeded in height in North America by Mt. Denali in Alaska, now thought by many to be 20,310 feet, and Mt. Logan in Canada’s Yukon, at 19,551 feet. Nevertheless, at 18,491 feet, Orizaba is no slouch. It’s easy to get to and inexpensive to climb, so it attracts mountaineers the world over wanting to climb high quickly with a minimum of hassle. It doesn’t hurt that it’s the 7th-most-prominent peak in the world. As I write this, in January of 2017, Popocatépetl is still out of commission for climbers (and don’t even get me started on Volcán Colima), so that would direct even more folks to Orizaba.

In March of 1976, I had flown from Canada down to Mexico City to do some climbing. To say I stumbled while on Popocatépetl, Mexico’s 2nd-highest, would be an understatement, so, still licking my wounds, I started towards Orizaba. Yes, I had reached the top of Popo, but barely, so I hoped to do better on the big one. Once down from Popo, I gorged myself in a restaurant in Amecameca, then started the drive to Orizaba. It took a few hours by freeway and lesser roads, but by 3:30 that afternoon I had arrived in the town of Tlachichuca. Speaking of the freeway, I had an exciting experience while driving there. I was zooming along, going downhill, when I saw something ahead of me in my lane. Both lanes were packed with traffic so I couldn’t move over, and I plowed into a cardboard box sitting there, at about 70 miles per hour. There was a mighty bang, and I feared the worst. Later, at the first safe opportunity, I pulled over to inspect the damage. The underside of the car was dripping with something odd. It didn’t take long to realize that it was contact cement, something I used in my work back home. What a mess! Oh well, it was a rental car and insured, so no big deal.

All the way back in Canada, I had heard through the grapevine that if you wanted to climb Orizaba you should look up one Señor Reyes upon arrival in Tlachichuca. When I rolled into town in my rented VW Beetle, he wasn’t around, but I did speak to his wife about hiring a Jeep and driver to take me up to the climber’s shelter high up on the mountain’s flank. Soon after that, a group of 7 Americans showed up. They had driven down from the States and wanted to try to drive the road in their own vehicle (I no longer remember what kind it was). I went with them, but we didn’t fare well – either we got off track, or they feared the road was too rough for them to drive. In any case, once back in town, I arranged with Sr. Reyes a truck large enough for all 8 of us plus our gear for the following morning. We arranged rooms in a place called La Casa Roja, and had dinner there too.

Early the next morning, the old beater truck arrived. We all piled into the open bed (it was a pretty big truck, bigger than a pickup), and two sat up front. It was a long, slow ride, the truck grinding its way up the ever-worsening dirt road filled with potholes and rocks. We stopped for a while at the village of Hidalgo at 11,150 feet elevation – there, our driver left us for a while and ducked into a house by the road for a meal – it may have been his home. After way too long, he returned and we continued. The road got even worse. It was a 25-KM drive from Tlachichuca to reach the Piedra Grande hut at around 14,000 feet. We quickly unloaded our stuff and our driver didn’t waste a moment starting back down, after agreeing to pick us up late the next day.

There aren’t a whole lot of big mountains you can climb by first driving up to 14,000 feet, so this was a pretty unusual start. Two huts were there: a small one that could sleep 10 people, and a big one that could sleep as many as 80. They were cold and stark – shelter from the storm, but that’s all. There were no facilities at all – no water, no electricity, no nuthin’, unlike the glamorous huts in the Alps and other places. Just a place to lay out your sleeping bag, that’s it. You need to bring everything you’ll need on the mountain with you up to the hut.

To put a bit of perspective on things as they stood at that point – here the 8 of us were, at 14,000 feet. I had just come directly from several days and nights on Popo, up high – up to 17,800 feet – and I felt great. These guys had just driven in directly from the USA, with no time at all up high to acclimatize. Even at the hut, they felt like crap. In their team, there were 4 men and 3 women, and the women felt even worse – I don’t know if they had any climbing background at all, but they quickly decided that they wouldn’t go for the summit – they’d wait at the hut until our return and keep each other company. There were no other climbers on the mountain at the time, so it seemed safe enough.

In the course of discussing the climb with the men, I strongly urged that we move higher to sleep. It would give us a better chance to summit on our one and only day on the mountain. They weren’t too excited about the idea of going even higher right away, as they too felt pretty crappy. I, on the other hand, felt up for anything. Maybe in their brain-addled state my reasoning made sense, because they agreed.

We set out for a higher camp – I’d heard that if we climbed up to the foot of the glacier, there were flattish bivi sites there, and also a source of water, flowing from beneath the toe. In 2 hours, we got there, and found a good spot to camp at 15,450 feet. All of the guys felt even more awful by then – nauseous, vomiting, pounding headaches – the classic symptoms of mountain sickness, just like I’d recently experienced on Popo. I, in turn, was feeling like a million bucks, as if I were at sea level – I had a good appetite (“are you going to eat that?”) We were camped in a tumbled area of rocky rubble at the toe of the glacier. As I lay in my sleeping bag, all warm and belly full, I stared up at the night sky, awash in satellites and meteorites, and overflowing with intensely bright stars. Overnight, it only dropped to +23 degrees F.

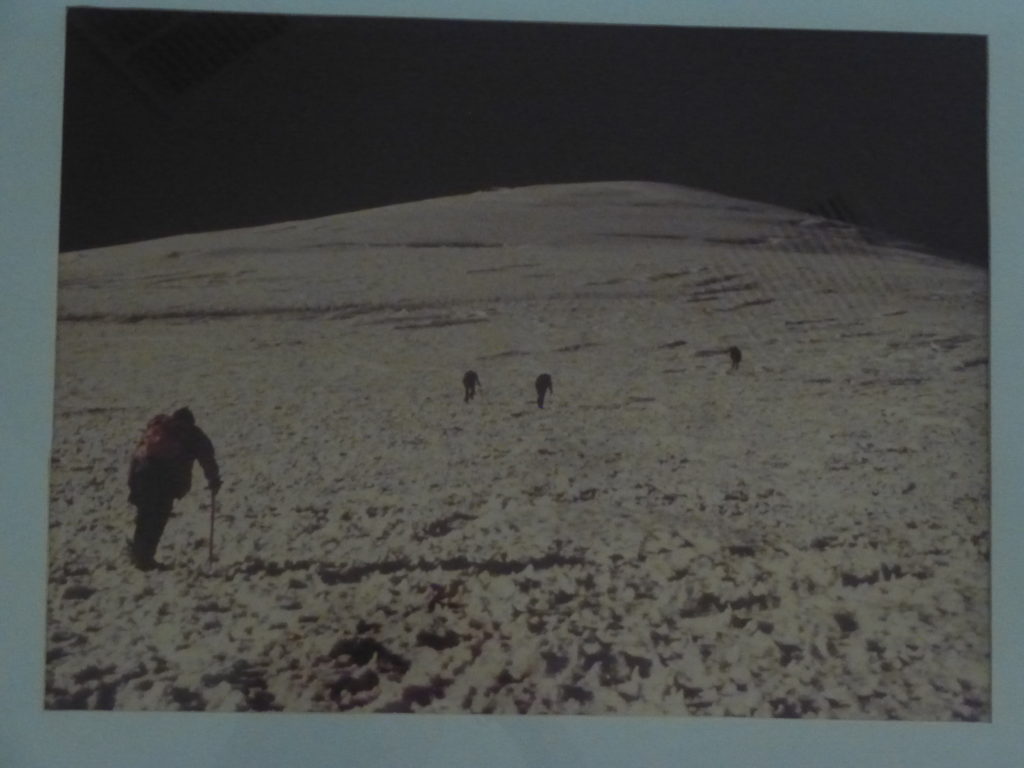

I slept well; the others, poorly. We arose super-early, and were finally climbing by 4:20 AM. Comet West was nothing short of spectacular in the early-morning sky. We moved well, and by sunrise at 6:20 we were at a col at almost 17,000 feet. Before the sun came up, the winds were fierce, making it feel much colder. When the sun rose, the air didn’t feel as cold, but at 17,500 feet my feet were freezing. We all moved up more slowly now, strung out over hundreds of yards up and down the mountain. This next photo is the only one I took on the climb which survives. Credit for the others is at the end of the story.

By 10:20 AM all 5 of us stood on the summit. Three of the Americans were vomiting, and all 4 of them had fierce headaches – I, on the other hand, still felt fine. The crater rim at the summit was steeply inclined, and its walls steep and rotten; the crater was very deep, and God help anyone who should fall in. A blissful half-hour was spent on top – the views were outrageous, and our camera shutters clicked non-stop the whole time.

Our descent was slow, due to the poor state of the others. I arrived back at the hut first, at 2:30 PM. The 3 women had fared no better, and were all feeling tremendously sick from the altitude. It snowed a bit during the afternoon while we all waited for our ride down the mountain, which arrived at 6:00 PM. The trip down was much quicker than the ride up, putting us back in Tlachichuca in only 2 1/4 hours. I spent another night in town, in a flop-house so seedy that the bed-sheets were black with filth, as if they’d never been laundered (I used my sleeping bag). The Señora who ran the place did manage to rustle up a plate of black beans and rice for my supper, and I considered myself lucky at that.

I spent a few days as a tourist after that, in Puebla, Toluca and finally in Mexico City. Two odd memories remain of those final days. The first was the result of not wearing sunscreen on the climb. All of the skin on my forehead came off one evening in my hotel room – crispy and hard, like a big potato chip, with bright pink skin weeping underneath. Sorry if that was TMI.

The second was more interesting. One afternoon, while driving my rented, shiny, new VW Beetle in Mexico City, I was pulled over by a traffic cop who was on foot. He told me that I had committed una infracción. It was obvious he wanted a bribe. I told him I didn’t need any hassles, as I was flying out in the morning for Canada. To this day, I remember his response: “Señor, I would like to help you, but who will help me?” Okay, hopefully I could make this go away, so I opened my wallet right in front of him, and showed him that I had a traveler’s check for fifty dollars US, and also the equivalent of five dollars in pesos. He was really pissed off, having hoped for a much bigger payday. The check was of no use to him, and the pesos were insignificant. Remember the Americans with whom I’d climbed on Orizaba? They had run into an identical traffic stop, and had been separated from 100 of their US dollars. He begrudgingly took the pesos and let me go, keeping a sharp eye out for his next mark.

Footnote: in the 41 years since I climbed Orizaba, the toe of the glacier on this route has receded all the way back to 16,100 feet due to climate change. Also, when I climbed, it was believed that the elevation of the mountain was 18,696 feet – compare that with the present, more accurate elevation of 18,491 feet).

Thanks to my climber friend Barbara Lilley for the use of her photos from her 1955 climb of the peak.