One fine spring day at the end of March in 2004, I made my way back out to the Tohono O’odham Indian Reservation. To get there, you head west on what we locals call the Ajo Highway, or more properly Arizona Highway 86. Just over 60 miles from downtown Tucson, you roll into Sells, the capital of the T.O. Nation. It’s not hard to find Indian Highway 19, which leaves from the west end of town and heads south. Once you’ve started on 19, you don’t drive the full 27 miles to the Mexican Border, or at least I didn’t this day. Rather, I only went half that to my turnoff.

I’m getting a bit ahead of myself, though. If you’ve never taken that drive, I’ll describe it to you. As soon as you leave Sells, you enter the Artesa Mountains. Peak 2891 is the first one you see, over to your left. The striking peak known as Suwuk Tontk is right beside it, and rises steeply up from the highway. As you continue, you go over a pass at about 2,500 feet – you are now next to Burro Mountain, which happens to be the 3rd-highest peak in the range. I had an interesting experience there just after Y2K. I was climbing the peak via its southwest ridge, and had already crossed over Point 2938. Scrambling up the last hundred or so feet to the summit, I happened to look up and stopped dead in my tracks.

There, standing on the ridge just below the summit, stood a deer, a buck. Not only was its body very large, but it had an enormous rack of antlers with many points. It stood looking down at me, unfazed by my presence. Normally, deer are very skittish in the desert and will run away quickly when they see a human – I see them all the time. This one was spectacular, not just because of his size but the amazing antlers, the likes of which I had never seen, anywhere. It was completely unafraid, stood looking directly at me, and was definitely the master of his domain. It was as if I had stepped into the movie “Bambi”, and was looking at the Prince of the Forest. He was quite mesmerizing. We stared at each other, unmoving, for perhaps a whole minute. Then, he slowly turned around and walked away from me, seemingly unconcerned, across the summit and down the east side. By the time I’d walked to the top, he had disappeared. It was a spiritual moment we had shared, one I have thought back upon many times over the years.

As one continues south on the highway, the mountains fizzle out into small hills on the left (east) side, but a large lobe of the range persists to the west, dominated by a sizeable peak known as Aspass Benchmark. Two months after my experience with the deer, I was climbing this peak from its west side. As I walked on to the summit, I had another remarkable experience, perhaps even more personal than that with the deer.

My eye caught a bit of movement on the ground at my feet. I was shocked by what I saw. A cactus wren, Arizona’s state bird, lay there on its side in the dirt. Attached to his breast was a 3-inch stem of teddy-bear cholla cactus, as big as the body of the bird itself and certainly heavier. Now for those of you who have not spent time in the Sonoran Desert, this cactus is the most feared. The spines have a microscopic barb on the end – it penetrates your flesh effortlessly with the slightest touch, but to pull it out will cause much pain and you will bleed. They look so soft and harmless, but how appearances can deceive!

The bird was completely helpless, the cactus spines sticking into him. Ants were on the ground and I could see several of them crawling on the bird. As I stood by him, he looked terrified. There wasn’t anything he could do, though, immobilized as he was. Of course, I was moved by his predicament. What could I do? I thought for a moment, picked up a small stick in one hand, and placed the other on the little guy, then while I held him down I pushed the cholla with the stick. It took a bit of wiggling, but soon I was able to pry the cactus away from the bird. Once done, I couldn’t see any spines sticking in him – they must just have attached to his feathers and not stuck into his skin. I think he knew I was trying to help him – he didn’t peck at me or struggle while I held him down. When he was free, he shook himself, stood up and flew a few feet, then stopped and looked back at me. He didn’t seem afraid, and it was almost like he was acknowledging my having freed him. He then flew away and down the mountain. I have a soft spot for all such creatures, and am easily moved to help them if I can.

Once past the end of the Artesa Mountains, the highway takes you right into the community of Topawa. With a population of just over 500, Topawa is one of the largest towns on the Connecticut-sized reservation. Only Sells, San Xavier and Santa Rosa are larger. The San Solano Mission church and school are there, as well as the Baboquiviri High School/Middle School.

Just past the town and a couple of miles to the west sit the Topawa Hills, climbed by Dave Jurasevich and me in early 2001. When you’ve traveled 13 miles from Sells along Highway 19, you come to an important junction. There, Indian Highway 2 heads west. As you start down it, off to your left (south) you can see Las Animas Mountain. Andy Martin and I climbed to Comely Benchmark, its highest point, in February of 2004. Only 8 paved miles on Highway 2 take you all the way to the village of Vamori. With its 47 inhabitants and sitting at 2,247 feet above sea level, this is about as quiet a place as you could ever find. The actual name in the O’odham language is Wamel, which means “swamp”. Aside from the 20-odd homes, there’s a community building with a baseball field and an outdoor basketball court, and even a playground for the kids – and of course, the village church, where the pavement ends. Probably the most prominent feature in Vamori is the wo’o, or pond. It is round, and over 200 feet across if full from rainwater runoff.

One way I could tell that the community had been there for a long time is that there are 3 different cemeteries. The oldest one is about a mile west of town and has 15 graves. Another is only a third of a mile from the church, on the edge of town, and has 80 graves. Finally, there’s the one I drove to on March 31st of 2004. It sits almost 3 miles west of town, an old dirt road leading to it, and has about 40 graves. I went to this one because it was a perfect starting point for a climb I wanted to do. As I parked, I couldn’t help but notice an abandoned hulk of a car, rotting away right beside the cemetery. How sacrilegious! The tribal members would never have done something like that – it could only have been abandoned there by Bad Guys who sneaked across the border while committing a crime (either moving drugs or people into the country).

It was a pleasant walk across the desert to the base of nearby Peak 2941, and a 600-foot climb to its summit. I left a register and was soon back at my truck.

My route continued on a good dirt road, skirting the southern edge of the Alvarez Mountains. Almost 5 miles later, I reached the southernmost tip of the range and the namesake of this story – Itak. All to be found were a few crumbling ruins, tucked in to the west side of a hill called Rocky Point, elevation 2,505 feet.

Nobody was living there, but certainly it had been some sort of community long ago. My evidence for that was its own nearby cemetery which hosted 80 graves. How long does a place need to exist to bury 80 of its dead?

I climbed Rocky Point to eyeball the surrounding countryside, but all that revealed was an old corral next to a large, dry waterhole for cattle. Itak – that’s the name shown on maps prepared by Anglos, so is no doubt the anglicized version. I don’t know what the O’odham spelling would be, nor do I have any idea of what the name means. Obviously, though, this place meant something to people for a long time.

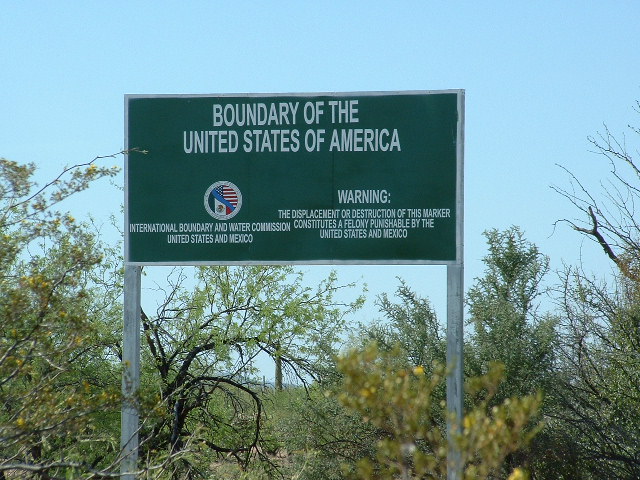

Once back down at my truck, I drove south on a well-traveled dirt road for about 5 miles to arrive at Mexico, where I was greeted by this sign.

Nearby was this gate in the barbed-wire fence that separated Mexico from the United States – we are looking into Mexico. Anybody could just drive into the US anytime they wished, scot-free. Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.

Less than a mile away, I found Border Monument 148. Beyond it, in the Mexican state of Sonora, sits a dramatic peak – I don’t know its name, but it may be in the Sierra el Cobre. Don’t even entertain the idea of climbing it, as it sits in an area notorious for its mayhem. The Mexican drug cartels are very active there, just waiting for opportunities to smuggle drugs and people into the US. A few miles from this spot, seven men were found murdered and beheaded at a ranch, a result of their cartel activities.

I had one thing left to do. Another mile to the west along the border sat Wolfley Hill, elevation 2,695 feet. I took this picture of its highest part, and did a quick climb.

I drove north away from the border, through Vamori and back home. It had been an interesting and pleasurable day, and for a change there had been no drama. In these border regions, anything could happen and does, more so now than ever before.