Fog – it’s not something we get very often here in the desert, only a few times a year. It usually happens in the cooler winter months, and of a morning following a good soaking rain on the previous day. That was the case one December when I set out to do some climbing. I arose early and drove in the dark for some time. As daylight approached, I found myself moving through thick patches of the stuff, forcing me to drive 40 on the 75-mph freeway. It was eerie, and I was shocked to see cars blow by me at full speed through the pea soup. An hour and a half after leaving home, I reached my turnoff and got ready for the climb.

The day was fine as I set out, the sun having already risen. I was in the Maricopa Mountains Wilderness in southern Arizona, here to climb a couple of peaks. When a couple of hundred feet above the valley floor, I could look back to the lingering fog.

To my north rose Big Horn Benchmark, rising 1,500 feet in the glow of early morning.

The long summit ridge of Peak 3020 made a grand sweep across the northeast skyline.

Because conditions were right for fog, they were also right for dew – all of the vegetation was dripping wet, and I was soon soaked to the knees as I climbed. No matter, it was a joy to be climbing up a steep rocky canyon towards my first peak of the day. Here is where I caught my first glimpse of what I guessed was the summit – it’s the one in the back with the sunlit ridge.

I stopped for a bit and had this view out to the west. The brown mountains in the foreground are part of the Maricopa Mountains in which I stood. In the distance, about 8 miles away, can be seen 2 other peaks. The long one on the left is Peak 2030; the pointed one farther right poking up behind the nearby ridge is Peak 2098 – they are both part of the Sand Tank Mountains.

As I got high up the canyon, I stood looking steeply up to what I thought was the highest bit. You do your best to estimate where the actual summit is, but sometimes need to tweak things – one area might turn out to be a little higher than the spot to which you climbed, forcing you to do some travel along the summit ridge.

I got lucky, getting it right the first time. As I scrambled up the last few feet of Peak 2700 I realized I’d reached a virgin summit – there was no sign of any previous visit.

As I prepared a register, I took in the view. Here’s something that caught my eye. Eighteen miles away, just north of the town of Gila Bend, sits the huge gas-fired electrical generating station. The conditions must have been just right for the cloud of steam to form and rise high into the air

I didn’t linger, soon starting back down into the canyon I’d climbed. As I descended, 3 kinds of plants seemed to be growing everywhere. Here’s one of them – botanist friend Jim Malusa says it is wolfberry, Genus Lycium, and is a member of the tomato family. The fruits are the size of a small pea and are edible – I’ll try them the next time I’m out. I don’t know if wolves like them, but no worries – there are no wolves here in the Sonoran Desert, so I won’t have to compete.

Another was pincushion cacti – these are usually less than 6 inches tall, and all seemed to be bearing fruit – I have heard them called desert strawberries, and are a sweet treat. Sorry for the out-of-focus picture.

The third one was a ground-hugging plant which has the tiniest flowers I have ever seen – check this out. Jim Malusa says it is Euphorbia albomarginata, a type of euphorb or “spurge”.

I’d been out for 2 1/2 hours by the time I found my truck after the thousand-foot climb. Nearby sat the remains of one who didn’t make it.

There was more climbing to be done, so I drove west to the town of Gila Bend and then northeast to a spot named Shawmut, about 45 miles in all. Have you ever noticed that railway companies have given their own names to places along their tracks, often dropping names on spots with no people living within miles. Maybe those names mean something to railway men, but to me they’ve always been something of a curiosity.

So there I sat, munching my lunch on the tailgate of my truck by the side of a railroad track. My plan had been to walk across those very tracks and head to my next peak, but there was just one problem – a train was sitting there, stationary, completely in my way. Hmmm, in all my years of climbing, I don’t recall ever having had to get around a train that was blocking my way. Upon closer inspection, I saw that there was a short ladder leading up to a walkway and then another ladder down the other side on the car nearest me. Here’s what it looked like from my side.

I had 3 choices: I could go over it, through it or under it. It was sitting still right now, but what if it started moving? Crawling beneath it seemed do-able, especially if I did it at the mid-point of one of the cars, but still a scary proposition even though trains start up very slowly. Using the ladder to cross over between cars made the most sense, and that was the choice I’d made when the train started to move. Almost imperceptibly at first, it soon picked up speed. I’m glad I had hesitated, as the train started moving just before I was about to set foot on it. The end of the train where the engine sat was so far down the tracks and around a bend that I hadn’t seen or heard it. No matter, within a few minutes the train had passed completely and the track sat empty. It was then that I noticed that a hundred yards away sat another track, a single one like the one near me. More on that later.

There was a nearby spot where a dirt road crossed over the tracks, but it had a puzzling sign, the likes of which I’d never before seen. What the heck is a private crossing? I can’t imagine the Southern Pacific Railway would allow just anyone to build one of these. It didn’t really concern me, though, as I wasn’t planning to drive across.

In the distance, I could see a long arm of the Maricopa Mountains. I knew my peak was up there somewhere among the many bumps along the ridge, but it’s an interesting exercise to see if you can spot your peak from far away. I had nothing but time to figure it out as I walked across flat desert terrain on this perfect 70-degree afternoon.

The nearer I got to the ridge, a route started to form in my mind. Climbing is all about route-finding, something we peakbaggers do constantly – it’s a necessary part of every climb. You could pick a route that’s easier or harder, one with more or less challenge – it’s up to you. It’s probably a good idea to choose one that’s not going to get you into trouble (something all of us have done at one time or another). Today, I’d go up a north slope for 500 feet, gain the northwest ridge, follow it and bypass 2 steep pinnacles, then up an open slope to the rounded summit. It had taken about 1 1/2 hours to reach the top of Peak 2264 after a thousand-foot climb. It was just the way I like it, no sign of any previous visit – no cairn, no survey trash, no nuthin’. It may surprise you to learn that of Arizona’s 7,500 summits, over 1,700 of them have no recorded ascents, so there’s plenty of pioneering work yet to be done out there.

From the summit, I had this great view into the heart of the Maricopa Mountains.

And here’s a look back the way I’d come. See the white line way out there in the upper right part of the photo? That’s a train on the tracks where I was parked.

I left my mark, then started down by a different route, one that was in shadow all the way down to the desert floor. In the northern hemisphere, December’s days are short and you have to hustle if you are to get much climbing done. There were still a couple of things I wanted to do before I lost the light completely. When I had re-traced my steps most of the way across the valley, I stopped to climb a small peak shown on the map as Ocapos Benchmark. By its south side, it was a steep, enjoyable scramble up a slope of tumbled granitic boulders. This was a pretty obscure spot and I didn’t expect to find any evidence that it had been visited. In the previous photo, look in the upper part and a bit left of center to see an area of 4 or 5 grayish bumps way out on the desert floor. Ocapos is in there, the highest bit of that.

I found the actual benchmark soon enough, left by the original surveyors way back in 1936.

I was prepared to leave my own register, a big half-gallon pickle jar which you can see in this next photo, in the shade to the left of my pack. Oh, one more thing – the peak on the far horizon just to the left of center on the skyline is the one I’d just climbed, Peak 2264.

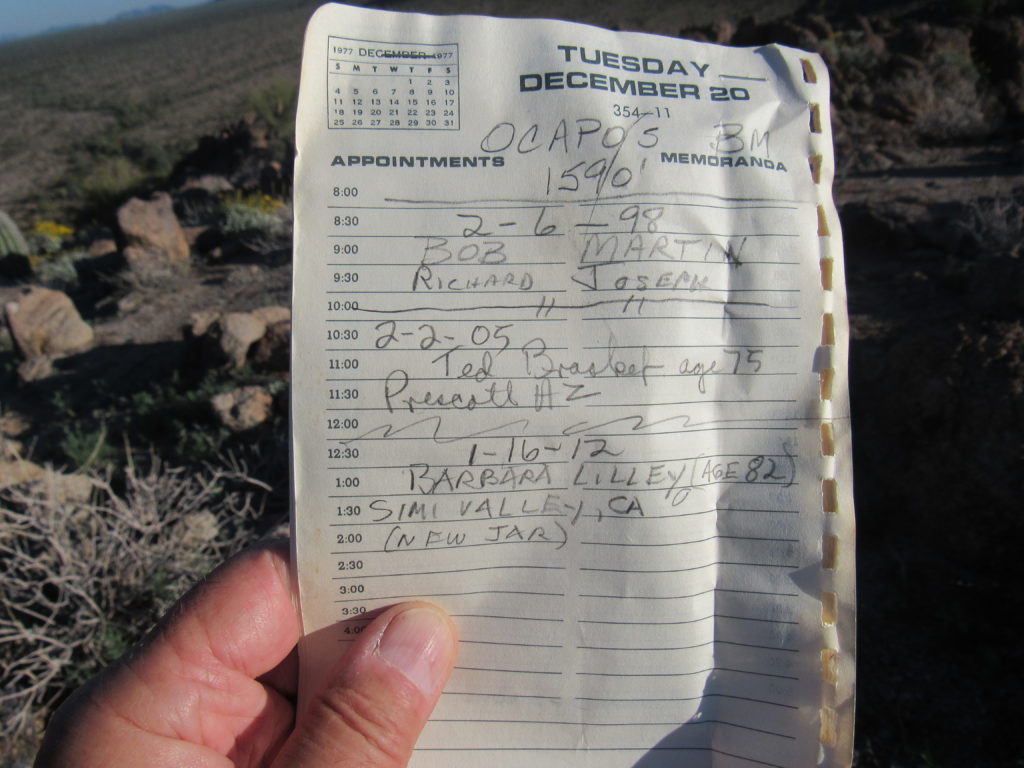

After a bit of poking around, I found a register that had been left by others, all folks that were well-known peakbaggers. I was happy to sign in.

From this mountain-top, I was close to my starting point. I could look down and just barely make out my truck on the other side of the tracks, half a mile away. Here’s something important I had learned during the afternoon of climbing in the area.

Trains were moving both east and west through the area on the main line of the Southern Pacific Railway. However, there was only a single track here. Every 30 minutes or so, a train would arrive and pull on to a long siding, stop, and wait for another approaching train to pass by on the main line – I don’t know how they decided which train had priority – and then once it had roared past, the one on the siding would start up again and move on. I could see this pattern going on for hours, so I knew that my timing would have to be good to avoid getting stuck on the wrong side of the tracks. I hustled down from Ocapos, crossed a brushy wash, crawled under a barbed-wire fence, hurriedly crossed both lines of track and arrived back at my truck. I was just in time, because moments later an eastbound train roared by.

There was one more thing I’d wanted to do all day. The topographic map showed a nearby cemetery, just a small square on the map with the label “Cem”. I noted the UTM coordinates on the map, then set out walking along the tracks, GPS in hand, to find it. As I rounded a corner, something white came in to view. Lo and behold, it was right where it was supposed to be. It was a wooden cross. The closer I got, I realized there were others.

I found 6 graves, all marked with recent white crosses. They were plain except for the letters “RIP” on them.

Someone had taken the time to locate these graves and make and place these crosses, someone who felt it was important to pay their respects to the dead. I assume, because their were no names or dates on the crosses, that the identities of those buried here were now unknown to the living. It made me think of the lines from a song I’d heard:

There’s one kind favor I’ll ask of you, See that my grave is kept clean.

There were mounds of stones on most of the graves – what that signifies, I’m not sure.

I wondered if these were early settlers who had passed away here; were they adults or children? I also wondered if they were Native Americans. And how old were these graves? Our topographic maps show many such spots, and in some cases even individual graves simply marked as “grave”.

When I was young, I cared little for history or for anything of the past – I scoffed at such studies as a waste of time. Now I know better and respect those who have gone before, and try in my way to learn something from them. I felt that the effort taken to visit this lonely site and pay my respects had been well worthwhile.