Here in the Sonoran Desert, there is a steady stream of people who cross illegally into the United States from Mexico and make their way north. They fall into two categories: smugglers carrying loads of drugs, and smugglers who shepherd groups of undocumented border-crossers north to the Promised Land. Usually, they try to reach Interstate 8. As they approach it, they make a call on their burner phone to arrange a pick-up, a ride to take them to their destination. This will usually be a major city like Phoenix.

So how far do they need to travel from the Mexican border to reach the interstate, or “Ocho” as they usually call it? That depends on the route they take. The closest the border comes to 8 is just outside the city of Yuma, where a mere 17 miles separate the two. It would seem to me that that would be a colossally stupid place to try, though, as the Yuma station of the Border Patrol must be all over that area like a cheap suit. Sure, some of them make it through, but precious few, I’d wager. The farther east you try to make the crossing, the wider is the gap. At Dateland, the distance has grown to 45 miles. By the time you’ve gone as far east as Gila Bend, you’re up to 70 miles. At the city of Casa Grande, the distance has ballooned to a full 84 miles.

Those distances are deceiving, however. Those of you who don’t live in the Sonoran Desert might think that you could just walk in a straight line from Point A to Point B and be done with it, but nothing could be further from the truth. Southern Arizona is full of mountain ranges that would be in your way, so you’d either have to go around the end of each one or climb up and over them. What I’m getting at is this – the actual distance you’d have to travel from Mexico to Interstate 8 would be much greater than the straight-line distance. It could easily be 50% more, or even double depending on the actual path you take.

This is not an easy journey to make. You have to be carrying everything you need. To reach the freeway near the Sand Tank Mountains requires 10 to 12 days on foot, and none of those are easy days. These travelers carry the ubiquitous black 4-liter water jugs, usually one or two of them – they are everywhere, littering the desert. If you don’t know where the water-holes are so you can replenish, the desert will kill you – period. Large numbers perish every year attempting the journey.

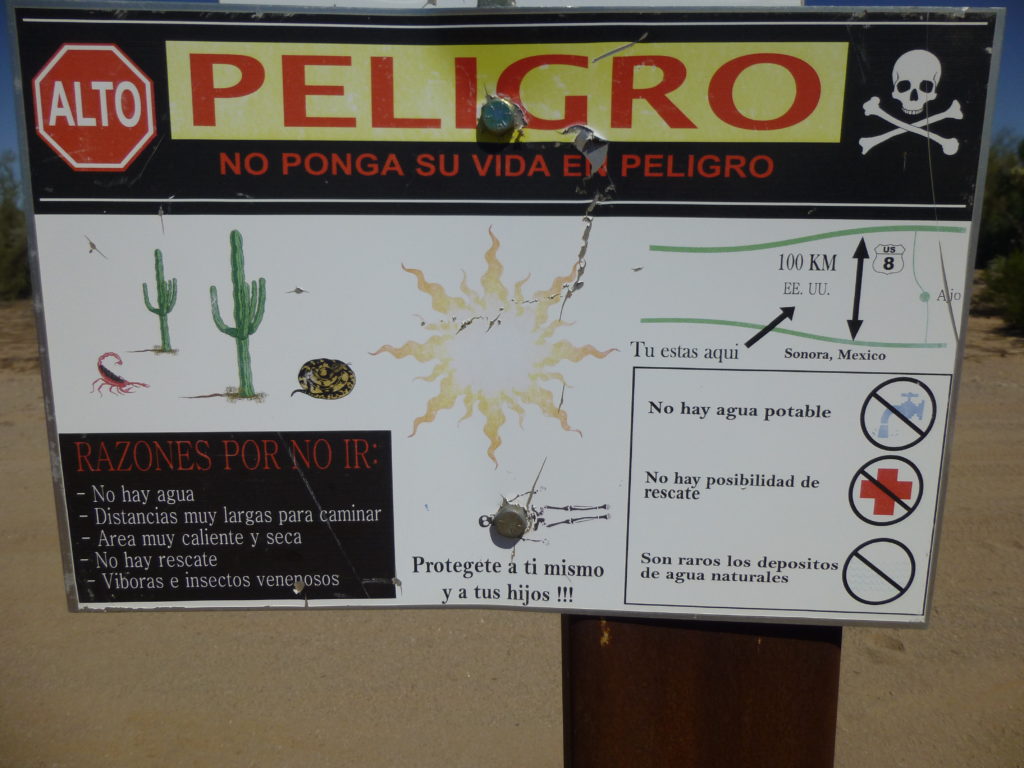

Many factors are at work to prevent you from completing this journey. Poisonous snakes, reptiles and insects; withering heat in the summer; freezing temperatures in the winter; a lack of water; no food or services. Here’s a sign that can be seen as you plan to sneak into the U.S.

Drug cartels now control all of this cross-border traffic. Even if you pay their fees and follow their rules, you could still be beaten, raped, robbed or killed by other crossers. Many who perish are never found again, leaving their families back home with no closure. More than 500 died in the year 2005 (just in the Tucson sector), and that doesn’t include all those who were never found.

As if those hazards weren’t enough, many who choose to make the journey must cross miles of active military ranges. Dangers there include exploding bombs, planes shooting at targets on the ground, and untold amounts of unexploded ordnance littering the land, any piece of which could be lethal (much of it lies just below the visible surface). Crossers could be spotted by military personnel or other law enforcement, promptly putting an end to their journey. Here’s a warning sign you might see on military land.

And then there’s their greatest hurdle – the tireless men and women of the U.S. Border Patrol. They have hidden sensors waiting to detect your passage on foot or in a vehicle; they can spot you from aircraft and drones flying silently overhead; they can see you at night with infrared detection. Not only that, those in their Borstar Unit are experts at following you, tracking you by day or night over any kind of terrain. If you’re trying to avoid the BP, you’re playing against a stacked deck, and the odds are definitely not in your favor. When you are apprehended, you will be treated fairly and humanely. They have EMT training, and have saved many lives out there in the desert. Here’s a sign that’s posted at one of their emergency beacons in the remote desert – zoom in to read the warnings.

In my 30+ years spent wandering in the desert (please remember that “not all who wander are lost” – Aragorn) I have been involved in the rescue of several border-crossers, and have found human remains more than once. This land is a harsh mistress, and brooks no mistakes. I don’t know how much word of these risks gets back to potential crossers in Mexico or other countries, because they seem to always make the same bad choices.

Okay, up to now I’ve been jabbering on about the fact that Interstate 8 has always been a logical goal for border-crossers. In fact, I’ve always believed that it’d be a fool’s errand for them to try to go beyond that – in most cases, it’s a long way to reach the next highway or road that could be an alternative pick-up point. So imagine my surprise when I was out climbing on a fine November day well north of Ocho and had the following experience.

Starting off my day was a quick ascent of a low desert peak about a dozen miles southwest of the town of Maricopa. Here’s a shot of it, simply known as Peak 2102.

That done, I drove a lot of miles of dirt roads to get to my main goal of the day, the high point of the Booth Hills.

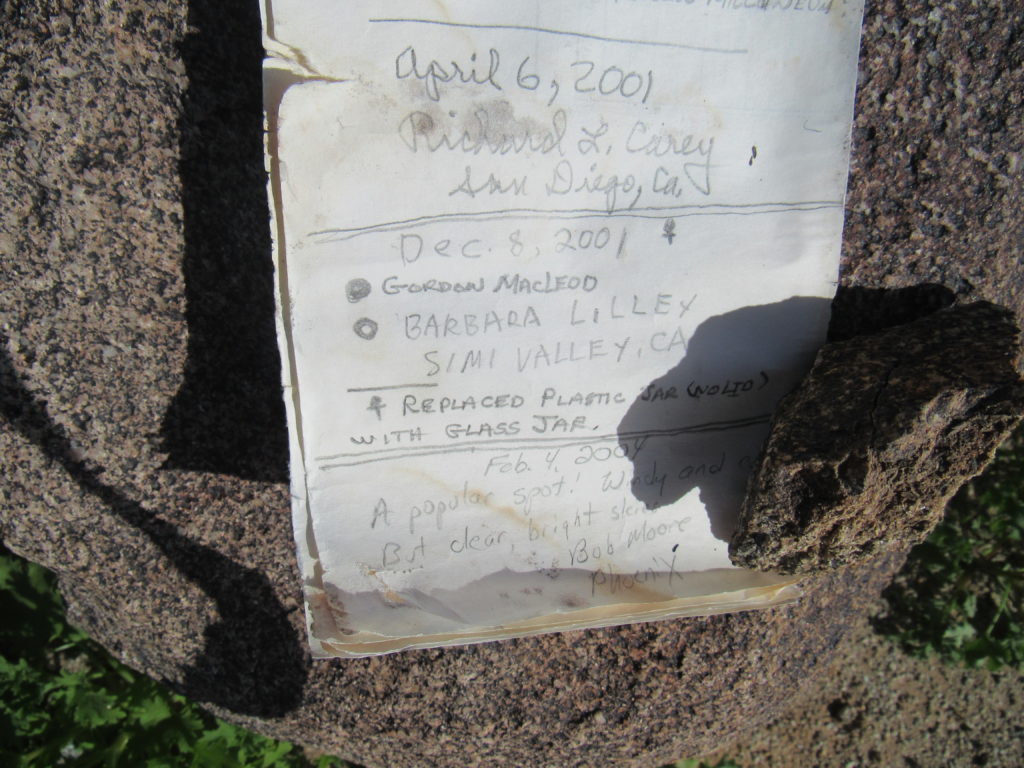

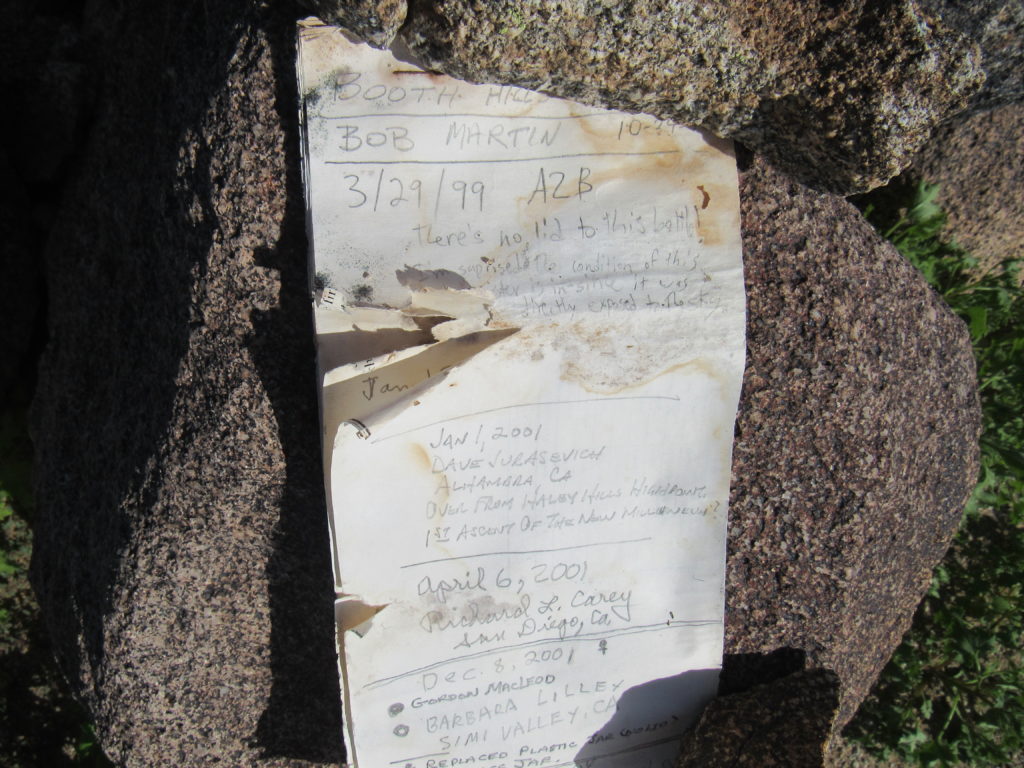

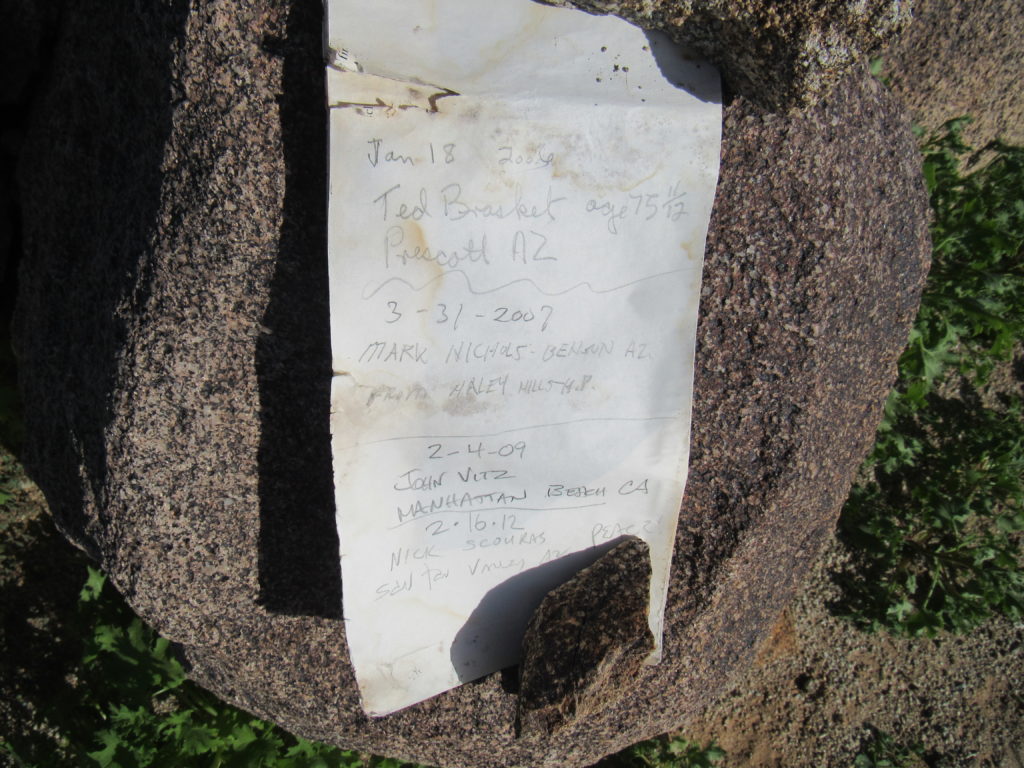

In and of itself, this is an unimpressive peak. There’s a register on its summit, where a total of 10 parties had signed in before my visit. Here’s what I found.

Here’s what the summit of Peak 2216 looked like, much the same as countless others.

But once I took a better look around, something caught my eye – in fact, a lot of somethings. Trash everywhere. You name it, I found it up there. It was as if someone had moved the contents of their house up to this mountaintop.

Why am I showing you all this trash? Well, the only reason it’s on the mountaintop is that agents for the Mexican drug cartels use this as a lookout. They keep an eye out for Border Patrol vehicles moving on the desert floor below. They use encrypted two-way radios to keep in touch with their people down below who are moving groups of border-crossers or loads of drugs to their destination farther north. In the short while I spent on top, I found no less than 5 car batteries among all that trash. The fifth picture up is a full-size cooler, the kind you’d take car-camping.

The cartel members who man these spots will spend a week or two at a time up there – if they’re caught, they’re soon replaced by others. Okay, there’s nothing unusual about that, you might say. But what is unusual about this mountaintop retreat is its location. It is north of Interstate 8. Any Bad Guys who’ve gotten this far have already passed Ocho a full 10 miles ago. So why would they have bothered to go past the obvious place to get picked up? To solve this mystery, I phoned a friend who is a supervisor in the Border Patrol, one who knows the area well. He said that as they’ve put more resources into policing the Interstate, it has forced the Bad Guys to move beyond it to more remote spots to conduct their activities and to get picked up. Holy crap! If I had just walked 12 days north from the Mexican border, then realized I’d have to go another few days beyond that, I’d be pretty pissed off.

The thing that bothers me about this, however, is the fact that now those of us who climb in the area north of Interstate 8 have to be looking over our shoulders, keeping a wary eye out for Bad Guys, in an area where there was no need to do so before. It’s bad enough that a large swath of the state has been overrun by invaders from another country, but it looks like that problem is about to become even worse.