After my long day yesterday, I slept well. It was hard to crawl out of that sleeping bag at 5:30 AM, even though the morning wasn’t too cold, at 43 degrees. Since the chance of anyone else driving up into this valley was near zero, I just left all my gear lying about. Nobody was going to steal it while I was away climbing, I was certain of that. In the off-chance that they did, they probably needed it more than I. By the time I set out, it was the late hour of seven o’clock. Because the valley was surrounded by high peaks, my campsite was still in shadow when I left.

An old road continued up the valley, and I followed it for a while. I kept looking at the east side of the mountain I was going to climb, now in full sunlight. It appeared that there were a couple of possible routes to the top, and if I followed one of them carefully, I should make it without too much difficulty. I knew that it had been climbed by others, but I had no idea which route they had chosen. There were cliffs all over the place up there, I just had to avoid them.

I soon left the road and made a beeline for the foot of the east slope, crossing a few small washes en route. My idea was to climb to the upper part of the east side of the peak and then find a way through some cliff bands near the top. I gained elevation pretty quickly and without problems, but for some reason found myself gravitating towards the north ridge. Once there, I found it was steep and rocky. Following the path of least resistance, scrambling up the rock, before long I was in a bowl and about 400 feet below the summit. Hmmm, not at all where I expected to be when I started this climb, but at least I was still moving upward. I was now on the west side of the ridge, and the east side, my original planned route, was not even visible.

I did an ascending traverse across the bowl in a southerly direction, knocking off a couple of hundred feet in the process, and found myself on another rocky rib. This, I followed straight up to the summit, with nothing worse than some Class 3 near the top.

It occurs to me that some of you may not understand what I mean by Class 3 so allow me a brief explanation. Here in North America, climbers use the YDS, or Yosemite Decimal System, to grade the difficulty of a climb. It covers all types of climbs, from the simplest to the most insanely difficult. Here’s a quick rundown of the classifications.

Class 1 The easiest – walking along a road or a trail or anyplace else where you do not have to use your hands at all.

Class 2 Any place where you need to use your hands for balance. Probably involves cross-country travel, no trails, possibly bushwhacking, but usually on a slope.

Class 3 Steeper ground, scrambling on rock, where you need to use handholds to climb. No real rock-climbing skills are needed. You might survive a fall, but would likely be injured.

Class 4 Handholds and footholds are necessary. Considerable exposure. If you fall, you would probably die. All prudent parties would be roped up. It is unlikely that protection would be placed.

Class 5 Real technical moves, roped climbing, placing hardware for protection; the holds require skill; serious injury or death is likely in an unprotected fall. Class 5 is subdivided into many categories: 5.0, 5.1, 5.2, up to 5.9. Then you get into 5.10, which is further divided into 5.10a, 5.10b, 5.10c, 5.10d. The same happens with 5.11, 5.12, 5.13, 5.14, 5.15.

That’s a quick overview of how we rate climbs – I hope it helps clarify things.

So back to my climb. It was 9:13 AM by the time I stepped on to the summit of Peak 2810, and I was glad to be done. Well, done is a bit of a misnomer, as climbing is a 2-way trip; you’re not really done until you’re safely off the thing and back out. The summit was a flat area with plenty of room to walk about,. The highest point was obvious, and there I found a register. Ten others had signed in before me, and no doubt, back in the day, miners who had worked the valley below had also visited. Here’s something that caught my eye.

Someone, I’ll bet a miner of long ago who had a lot of time on his hands, had chiseled initials and a date deeply into the native rock – quite impressive, actually. Who knows the story of E. F. C., but they had been there in March of 1915. This was a nice place to take a break, with views to die for, so I spent a while.

I had a decision to make, and that was how to best get down and back to camp. Usually, I go for the sure thing – that would be the way I’d come up – better the devil I knew than the one I didn’t. However, I had this nagging thought that there were easier ways, ones that I vaguely remembered as I glassed the east side from camp. Going back the way I’d come up seemed a bit complicated and messy, so I thought I’d look for another, one that was more direct and easy. If I were to start walking along the easy summit ridge to the southeast, I had a high degree of confidence that I’d find an easier descent route. Here’s a look out along that ridge.

I strolled along the narrow ridge, slowly losing elevation, and while I did I kept looking down both sides for a break in the steep cliffs, a spot where I could descend, preferably on my left (the side where the valley was where my truck was parked). I didn’t see anything encouraging, so I kept going. I was running out of ridge, and starting to be concerned. Ahead of me was the nose of the ridge, all cliffs, so I needed to find an exit, and soon.

My luck ran out. I stood at the end of the ridge, cliffs on 3 sides, with no way to continue. There was no choice but to retrace my steps back up and along the ridge. Now I couldn’t afford to be choosy, I’d take whatever I could get to get me off this lofty ridge. Hmmm, was that a way down? – I couldn’t see all the way, so there was still a chance of getting cliffed out down below, but it was worth a try. Zigging and zagging, I dropped down through little cliff bands – I was on the wrong side of the ridge, the side away from my truck, but beggars can’t be choosers. I’d figure it out later, all I wanted right then was to get down. I had dropped a good 150 feet, when I was stopped cold by a cliff I wasn’t willing to attempt to climb down. So, back I went, all the way up to the top of the ridge. This sonovabitch was turning out to be more challenging than I had planned; I was now resigned to going back up to the summit and then down the original route I’d taken up earlier in the day – at least that was a sure thing.

I was still near the nose of the ridge, like being on the prow of a ship, when something caught my eye. Was that a break in the cliffs, something I hadn’t noticed before? I walked cautiously over to the edge and peered over – dang, that might just work. It was a steep, broken gully – I couldn’t see all the way down because it took a right-angle turn part-way, but it was worth a try. It was steep enough that I had to face in to the rock to climb down, and of course the rock was loose crap, but bit by bit I made it down the toughest 50 feet of Class 3-4. It worked, and I let out a whoop when I stood on safer ground below. I wasn’t out of the woods yet – there was another 100 vertical feet of steep, loose ground, but nothing as bad as the gully. I soon reached a low point in the ridge, about 300 vertical feet below the summit. Here’s a look back.

And here’s a close-up. The view is somewhat foreshortened. Where the line is dashed, the route is hidden from view.

My plan was to drop down to the valley below from the ridge I was now on, but I had to find a decent route. Gullies descended from several notches in the ridge, but I had to inspect several of them to find a reasonable descent route, one that wasn’t blocked by cliffs at its head. It took a while, and even involved climbing uphill farther east along the ridge, examining several before I found a candidate. It was a steep descent through jumbled terrain to get to the bottom of the huge bowl northeast of the summit. In the shade of a palo verde tree half-way down, I stopped for some lunch and a bit of a rest. That done, I picked up an old mining road lower down and walked it the rest of the way to my truck. Here’s a look back to the peak on my way out.

Hindsight is always 20-20, right? I should have either made notes or even a sketch of the east side of the peak before starting out, something to use as a reference once I became a flyspeck up in that huge bowl, surrounded by terrain I could no longer put into perspective. I’m just glad it all turned out okay. My route involved over 1,500 feet of climbing and had eaten up 5 hours. It felt hot by the time I reached the truck. I rested in the shade and ate some lunch. They had predicted a high of 86 degrees today and it felt like it. While I ate, I found a tick crawling on my arm – I hate those things! Then began a search of my clothes and my skin to see if I could find any more of the little bastards, and fortunately I didn’t. As I relaxed, I even considered cutting the trip short and heading home, but that was just the tiredness talking.

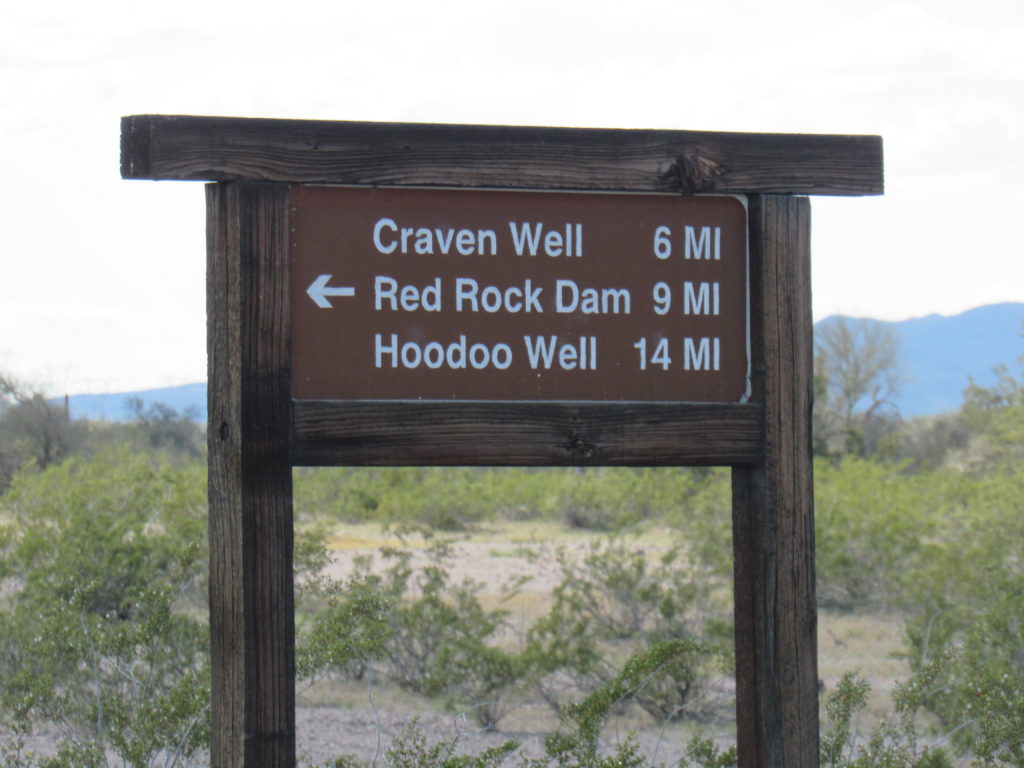

I packed my gear into the truck, turned on the air-conditioning, and set out north back out of the valley. A couple of miles later, I reached an important junction and had to make a decision. At that point, I had decided to keep climbing, so would I go left or right? If I turned right, it would take me to 5 more peaks I could climb; turning left would take me to 10 or more. To quote Mr. Frost:

I shall be telling this with a sigh Somewhere ages and ages hence Two roads diverged in a wood, and I – I took the one less traveled by, And that has made all the difference.

Many hard miles later, I made it out to a major powerline road and followed it west back into the Kofa National Wildlife Refuge. After a while, my journey took me south on what was known as the Kofa-Manganese Road, a lesser but still-decent dirt road.

Minutes later, I saw a vehicle approaching and pulled off the road to let it pass. It slowly pulled up to me and stopped – it was then that I saw the KNWR insignia on its side, plus the words “Law Enforcement”. The officer was about my age, and we had a good talk. I had wondered about some of the more obscure roads out there, and he was a wealth of information, answering all of my questions. After thanking him, I moved on.

Soon afterwards, I turned off on to a side road, blocked a hundred yards later, and parked. A few chapters ago in this story, I told of my experience at the Sheep Tank Mine. It turns out that this is the other way into it – it runs south for 9 miles to end at the front entrance of the mine. This road has been part of a wilderness area for a long time, so it is being reclaimed by the desert. It was an easy mile’s walk on the old road, then a quick ascent via the north ridge of Peak 2164. At least 4 others had been there before me. I even managed a quick call home from the summit before walking back to my truck. I had only climbed 2 peaks today, but it was enough. My tally for the trip was 21 summits.

The day dawned with a solid overcast. After breaking camp, I continued west along the Kofa-Manganese Road and soon arrived at Craven Well. This had been set up to furnish water for animals (but of course humans were welcome to partake).

It’s a clever arrangement they use in remote locations like this. Solar panels charge batteries which power a pump which raises water from the well into a tank which gravity-feeds it into a trough where animals can drink.

Nearby sat Peak 2390. I walked the short distance to it, climbed it by its northwest ridge, signed in to the register and was back at the truck in little more than an hour.

As I continued, the road turned south. A few miles later, it took me right past the highest peak in the range. At 3,348 feet, New Water Benchmark towered above its neighbors. I didn’t stop to climb it, as I’d already done so 30 years earlier. Here’s a view of its west side, the one that most climbers use to get to the summit.

The road climbed slowly uphill, reaching its highest point at 2,450 feet at a place called Red Rock Pass.

I parked near the pass and got ready to climb another peak. I know this one doesn’t look like much, but it is one of only 3 in the entire range that exceeds 3,000 feet in elevation.

Three friends had stood there before me atop Peak 3090. I signed in and headed down, but not before I took these photos west into the heart of the Kofa Mountains.

It wasn’t until I finished my trip and had a chance to do a little research that I realized what 2 of the peaks seen in the above photo actually were. The pointed one on the left end looks like this, and is named Squaw Peak.

And the one closer to the middle is this one, known as Summit Peak. It is 4,580 feet high and very technical, earning a rating of IV, 5.8, A3. It is 12.2 miles away.

Once back to my truck, I continued south on the Kofa-Manganese Road, as there was one more I needed to climb to finish off this end of the range. It was a quick scramble up to the top of Peak 2770, right beside the road. A popular spot, there were 8 prior ascents. I heard a distant noise while on the summit, and soon spotted the source. Down below, a caravan of 6 quads was heading north on the road where I was parked – they passed right on by.

At the base of the peak ran Red Raven Wash, my old friend which I’d visited in several other spots. Even here, close to its source, it was a substantial watercourse (dry, of course, probably 99.9 % of the time).

There wasn’t much more I could do here. Yes, there were still 8 peaks unclimbed by me in the range, and I wanted to complete my project by doing them too, but it was going to require another trip. I headed back to last night’s campsite, a tranquil spot where I’d spend one more night before heading home. The weather was supposed to be uneventful overnight, so I cooked a meal and settled in. Much to my surprise, near sunset a squall blew in and gave everything a good soaking. Remember Peak 2164, near which I’d camped last night? I had this nice view of it with a double rainbow.

The skies cleared as quickly as they had darkened, and all I had to do was watch the light fade and the stars come out.

In the morning, I packed up and made ready to leave. This had been a very satisfying trip, spanning 9 days. I’d driven 144 miles of dirt roads to bag 24 peaks, and every one of them had been worthwhile, and some of them quite memorable. I wasn’t done yet, however. The others would have to be climbed in a future trip, so stay tuned for the conclusion.