Flat tires

Of these, I’ve had my share. I’m not talking about one you might get on a city street, but rather the ones I get when I’m out driving some tired road in the remote desert or on a mountain peak. There was a time when I used to carry 2 spares, mounted on rims, and there came a day in the winter of 2006 when I used them both. No sooner had I replaced one flat when, not five minutes of driving later, I punctured another. Thank God I had that second spare.

Back in late June of 1989, I had driven into a remote valley to climb a big peak at daybreak. As I was getting ready to set out on foot, I saw that a tire was quickly going flat. This was a different vehicle than the one mentioned above, and it had one of those locking wheel nuts on that wheel. Should I take the time to change the tire now, or wait until I got back from the climb? Since it was going to be well over 100 degrees later, I decided I may as well get the climbing done now in the cooler part of the day and deal with the tire later – after all, it wasn’t going anywhere. A few hours later, climb over, I was back at the truck and set to work to change the flat. It didn’t take long to discover that the special tool used to remove the locking wheel nut didn’t work – it didn’t grab the nut properly and just spun uselessly on the nut. Wow, that sucked!! It meant that I couldn’t take the wheel off of the truck to put on the spare. The other 5 nuts were the conventional type and I removed them easily with the lug wrench, leaving just the locking nut in place.

What to do? This called for drastic action. In my tool box, I found a baby sledge hammer, about 3 pounds. I started whaling away on the offending nut, and found I could bend the stud on which it was mounted. Then I’d bend it back in the other direction as far as I could. Back and forth like that, over and over, until eventually the stud fatigued enough that it broke off. This all took quite a while. There were still 5 other studs to which I could attach the spare, so in the end it all turned out okay, and I made it back out okay. Back in town, a repair shop removed the mangled stud and replaced it. You can bet I removed all the other locking lug nuts and threw them away.

Another year, another June day (this madness of climbing in June has got to end!), and I returned to my truck after climbing 4 peaks in a big loop. Even before I reached the truck, I could see that a tire was flat. It was already 101 degrees. It took an hour of hard work to get the tire changed (those truck tires are heavy, and awkward to wrestle), but I won out in the end. A few hours later, it hit 110 degrees in that part of the desert. Without exception, every flat I’ve ever had while driving out in the desert turned out to be a sidewall puncture, not a one of them through the tread.

Conquistador Helmet

After I had summitted Cerro Aconcagua in South America, I returned to base camp and sold some gear to a fellow from Toronto. We kept in touch, and he even visited me here in Arizona. He said his father loved to come here to spend weeks away from the cold Ontario winter. Nothing unusual about that, right? However, one winter the father was walking in a sandy wash about 75 miles south of Tucson when he spotted something sticking out of the sand. He excitedly dug it up, and was amazed to see it was a Spanish conquistador helmet, and it was in good condition. It would have dated to the 1600s or 1700s. He decided to give it to a museum in Tucson. Wow, that wouldn’t have been my choice – that helmet would be gracing my home if I had found it.

Dolor de Garganta

They say it has never rained at Plaza de Mulas, the base camp for the Ruta Normal on Cerro Aconcagua. Because it sits at 14,000 feet elevation and is cold and dry, it only snows. I can believe it. The first time I was ever there, I developed a sore throat within a day or two. Time passed, and it didn’t improve. The Cruz Roja had a little outpost there, and the folks who manned it were happy to examine anyone who wandered in for help. When I went to see them, they said I had a throat infection and gave me some antibiotics, all at no charge. They also said to sleep with something covering my mouth, like a balaclava, so I wouldn’t be mouth-breathing frigid air – breathing through my nose was fine. I took their advice, I took their pills, and settled in. It was a long spell, 10 full days, before I felt well enough to move higher up the mountain.

Too Much Gear?

In preparing for a trip to South America to climb, I had two huge duffel bags full of gear, and that didn’t include fuel, food or water which I’d pick up once I got there. Once settled into the nearest city, I started hauling through all that stuff and felt I could leave some of it there with friends. When I traveled to the last outpost, a village which would be my jumping-off point where I’d start my trek into the mountain, I looked through it all again and realized that I could leave some of it there for my return. Mules brought the rest of it to the base camp. Once at that camp, I knew that whatever I needed at that point would be going up the mountain on my back, so I surprised myself by how much more of it I decided I could do without. I left the excess with others at the camp for safe-keeping. After my climb was over and I was back at base camp, it was happy to give a lot of it away or sell it to others there. Less and less and less, it made me realize just how much stuff I could actually do without.

Military Rip-Off

Several years ago, I was climbing in an area of the bombing range where you weren’t technically supposed to go. While there, I came upon a cluster of old military vehicles that had been decommissioned and were going to be used for target practice or whatever else the Air Force had planned for them. As I was poking around, this one caught my eye.

What really shocked me was the metal tag I found affixed to the back of it. Here is what I saw.

Apparently it was a mine-resistant vehicle. What does that involve, a lot of extra metal underneath it in case a mine explodes below it? I can understand how that would add to the cost, but $733,000.00? It seems excessive, to me at least. When you consider what the military has paid for other items, it makes sense that they overpaid for this vehicle as well. For example, I went online and learned about a publication called “The Pentagon Catalog” which describes many items and what the military pays for them. Among the many eye-openers were the following: $640 for a plastic toilet seat; $435 for an ordinary claw hammer; $37 for a screw; $285 for a screwdriver; $7,622 for a coffee maker; $387 for a flat washer; $469 for a wrench; $214 for a flashlight; $437 for a tape measure; $2,228 for a monkey wrench; $748 for a pair of duckbill pliers; $74,165 for an aluminum ladder; $659 for an ashtray. These are all real prices, so maybe if we put the truck into context, three-quarters of a million bucks might be considered a bargain.

The Bolivian Navy

Why in God’s name would Bolivia have a navy? Since the War of the Pacific, in 1879, Bolivia lost a chunk of its territory to Chile, and that chunk was its seacoast. The country has been completely landlocked for well over a century, and treaties that have been enacted since then pretty much guarantee that it will stay that way. Like Paraguay, Bolivia has a poor track record when it comes to winning wars with its neighbors. Nevertheless, present-day Bolivia has a navy about 5,000-strong, and they are occupied with two tasks. They patrol the country’s large rivers which are tributaries of the Amazon, on the lookout for smuggling and drug trafficking. In addition, they maintain a presence on Lake Titicaca.

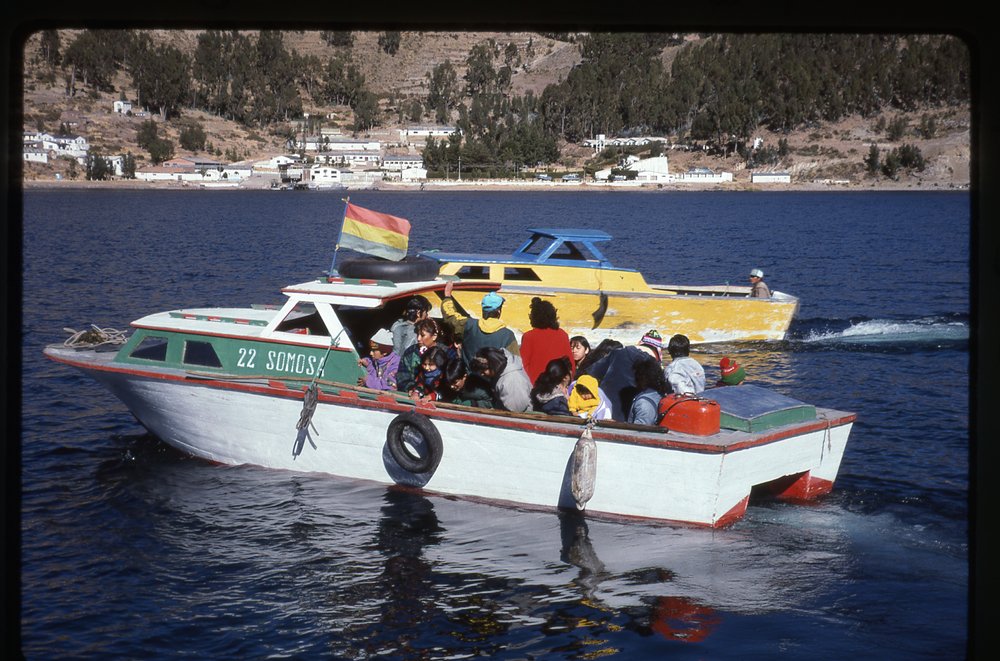

If you travel from La Paz to the lake, it is likely that you will travel through a small town called San Pablo de Tiquina. It straddles the Strait of Tiquina, the quarter-mile wide channel joining two parts of the lake. To continue, you must take a small boat across the channel and pay the princely sum of 20 cents for your seat.

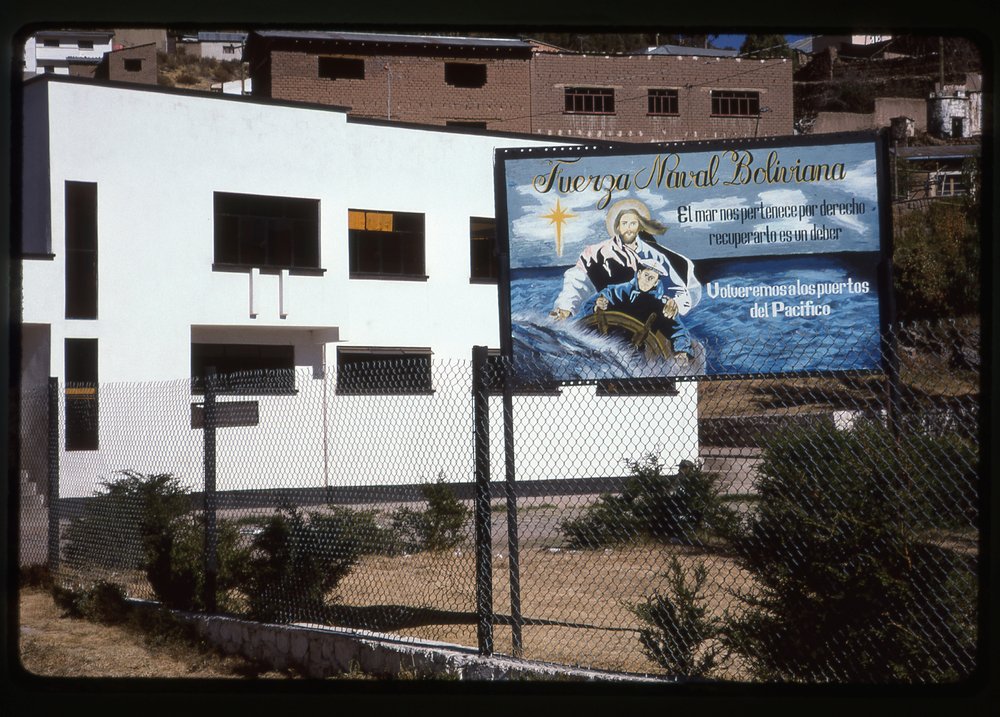

The presence of the Bolivian navy becomes obvious here in Tiquina. This picture is beside their building, and I love what it says and shows. Jesus is on board the vessel, standing behind the young sailor, with one hand on the wheel and the other on the fellow’s shoulder. The words translate as follows:

Bolivian Naval Force The sea belongs to us by right, recovering it is a must. We will return to the Pacific ports. (In the sense of regaining the ports.)

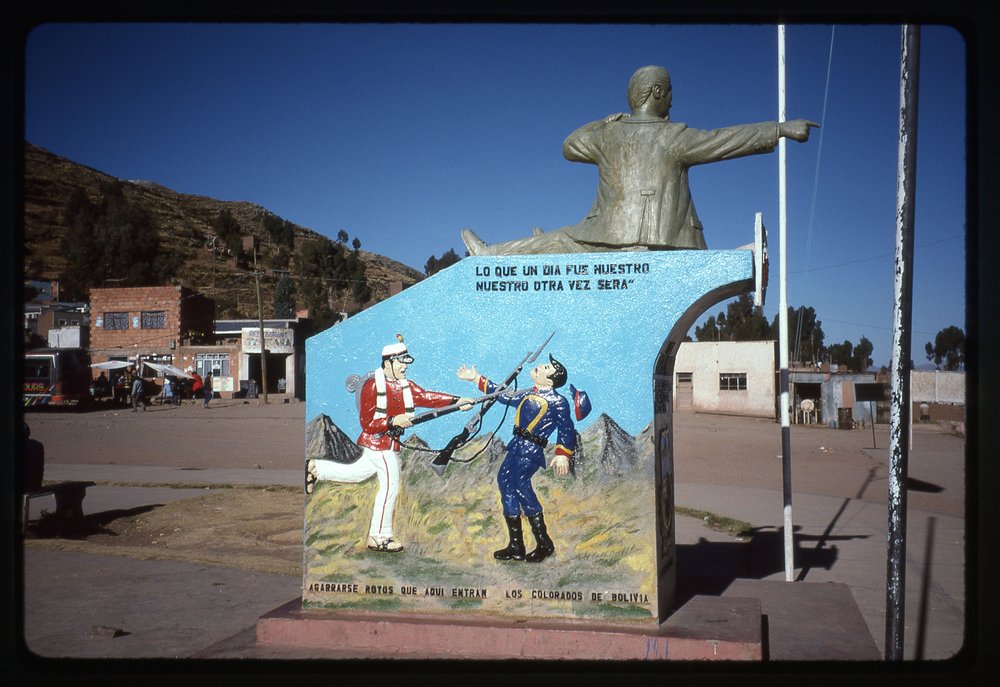

In addition to the sign, there is this striking monument.

The words at the top translate as “What was once ours will be ours again.” The words at the bottom are hard to translate, but I think are meant to give the impression that if you mess with Bolivia, you will pay dearly (as shown by the Bolivian soldier shoving his bayonet into the neck of the enemy!)

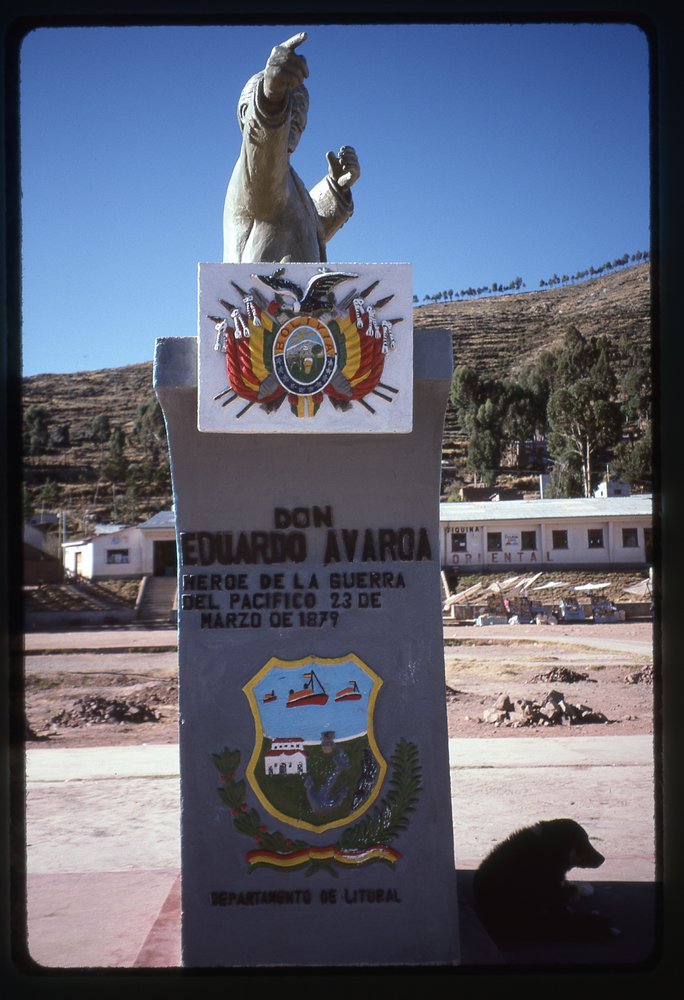

Here is the monument seen end-on. The words say:

Don Eduardo Avaroa Hero of the War of the Pacific March 22, 1879 Coastal Department

And finally, the view of the front of the monument.

The words at the bottom say “Bolivia reclaims her exit to the sea” with a variety of Bolivians at the shore, while Avaroa sits on top and points towards the Pacific. All quite dramatic, don’t you think? Each year, Bolivians celebrate the Día del Mar (Day of the Sea), so as to not lose sight of what they feel is rightfully theirs.

Many Nations

During the many days I’ve camped at Plaza de Mulas, one of the base camps for Cerro Aconcagua, I had the pleasure of meeting climbers from quite a few countries. The ones I knew for sure were as follows: Hungary; Colombia; Australia; France; USA; Japan; England; Argentina; Chile; Germany; Canada; Spain; Peru; Switzerland; Italy; South Korea; Bulgaria; Mexico. I’m sure there were climbers from other countries that I did not meet, as there were as many as 300 climbers in the camp at one time.

Giant Spider

I was walking along a trail in the sub-tropical forest near Iguazu Falls in South America when I was stopped in my tracks by a huge spider web which stretched completely across the path. Guarding the web was its maker, a spider bigger than anything I’d ever seen. Including its legs, it was bigger than my open hand, and I gave it a wide berth. Fluttering nearby were a couple of those huge iridescent blue morpho butterflies, the kind I’d only ever seen in collections. And high overhead, a troop of capuchin monkeys was making their way through the trees. Some of them were mothers with babies clinging to them. It was a magical moment, one that left a strong impression to this day.