This is another of those stories that I previously published, but at that time I didn’t have any of my photos from that climb. Well, as luck would have it, I have found my lost photos. So now I can present the story to you again, complete with my photos taken in 1976. I hope you enjoy it, so here goes.

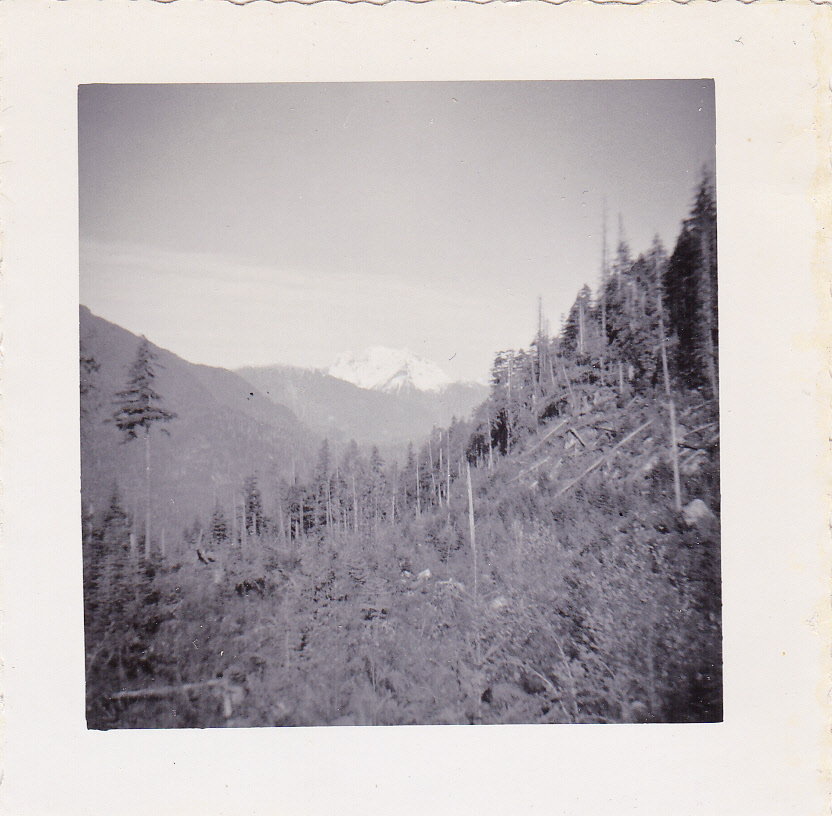

When I was 14 years old, we moved from Montreal to Vancouver. Actually, not Vancouver itself but a small town 50 miles to its east. A year later, in 1962, I climbed my first peak – it was a small, wooded summit about 10 miles north of my home. The climb, aside from being historic (for me, that is) was otherwise very ordinary. However, it gave me a first glimpse of a big peak farther to the north – I didn’t even learn its name for another year, but it sure blew my mind to see it. It was massive, tall and covered with lots of snow and ice. Here’s what I saw. This funky black-and-white photo was taken with an old Brownie camera I’d borrowed from my mother. There’s the peak dead-center. You may have to squint to see it, but it’s there, right in the middle of the photo.

I didn’t know it at the time, but I was looking at Mount Robie Reid. Its summit stood 12 miles away and reared 5,300 vertical feet above where I was standing. Trying to climb it was the farthest thing from my mind – I was just a kid – but I sure was impressed by what I saw.

After graduating from high school, I moved away to attend university, and the years rolled by. In 1973, I moved back to that same small town and took up an unusual occupation – “touch-up man”. You’re probably wondering what the heck that is, so I’ll tell you. There were several towns within a 30-minute drive of my home, and each of them had several stores that sold furniture. Since humans are a fairly careless lot, furniture would arrive at the stores with some kind of damage, and also be delivered to their customers’ homes with a dent or a scratch. My job would be to repair that damage. I had a kit of materials that I’d use (I’d taken a 3-evening course in how to do it), and so either in the store or as a service-call to the customer’s home I’d work my magic and make the mishaps go away. I worked for myself, and so being self-employed I could arrange my own schedule. Once I realized the incredible flexibility this gave me, I started climbing like a fiend.

Robie Reid started to show up on my radar. The only problem was that I couldn’t get anywhere near it – no roads came even close. In 1974, the first climber’s guidebook to southwestern British Columbia was published, and it suggested using a boat to travel 15-or-so miles up Stave Lake and strike out west towards the peak. Okay, that sounded all good and well – I was always up for a bit of adventure. After spending a lot of time pondering this, I approached my brother-in-law Ron. He had a small boat and an outboard motor, and although he wasn’t interested in climbing the mountain he was okay with giving me a lift up the lake. We put in by the dam at Stave Falls and headed north. It was a bit choppy, but we still made good time. However, after about 5 miles we went around a corner and entered the main body of the lake. Everything went to hell quickly after that – the wind picked up and the waves got crazy. After a short time of being violently tossed around, we decided that we wanted to live more than we wanted to die, so turned the boat around and headed home. That was the sorry end of my first attempt at Robie Reid.

Hmmm, maybe it was time to try an overland approach. A couple of weeks later, I drove back to Stave Falls, then up an old road on the west side of the lake. It didn’t go but a few miles, still leaving me a long way short of my goal. I knew that in advance, though, so when I parked I knew I was in for a time. Things quickly went to hell in a handbasket – alternating between swamps and bushwhacking, my patience soon ran out. I remember the moment when I called it quits – swatting mosquitoes as I looked across the next stretch of bog. What a pathetic effort! I turned tail and headed home. Now I was more determined than ever – Robie Reid had become a grudge peak, even though I’d never set foot on it.

One of the towns I serviced with my work was called Haney (it’s now known as Maple Ridge), and the biggest store in that town went by the name of Fuller-Watson. It carried appliances and furniture, and I’d stop in there at least weekly to see if they had anything for me to repair. I got to know the folks who worked at the store, some of them pretty well. One day while doing some work at the store, I learned that the 2 guys who handled the deliveries for the store owned a boat. Theirs was more substantial than Ron’s and seemed more likely to get us where we needed to go. Tom and Bruce seemed agreeable to take me and my friend Mike to the mountain – all we had to do was pay for the gas. It would have to be on a weekend so we’d fit in to their schedule, and we actually had it arranged a couple of times but had to cancel due to poor weather.

Finally the big day arrived. Very early on Saturday, July 30th, 1976 Mike and I drove from our town to the boat launch at Alouette Lake. There, we met the guys with their boat, which was soon in the water. Eleven miles later, we stepped off on to the shore at the north end of the lake. The plan was that they’d be back to pick us up late the next day. Within minutes, they’d turned the boat around and were soon out of earshot. There we were, just the 2 of us at the base of the mountain, at an elevation of 400 feet above sea level. All we had to do now was climb 6,500 vertical feet to the summit.

Robie Lewis Reid had a lifelong friendship with Frederic W. Howay. Both started their working lives as teachers after passing the Provincial Teachers’ exam in mid 1880′s. Later they studied Law at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia before returning to judicial careers in British Columbia. Today they are immortalized in two mountains: Mount Robie Reid (6,847 feet) is the easier one to access and climb while Mount Judge Howay (7,422 feet) is a more adventurous undertaking.

From where the boat set us on to the shore of the lake, a rough trail began. One of the first things we had to do was to cross a Burma bridge that spanned the Alouette River. If you’ve never used one of these, I can tell you that some people do not do well with them. The one we used that day was the most primitive type, just 2 cables strung one above the other. Some people have a problem with the water running swiftly past beneath their feet; others just can’t get the hang of it, trying to keep their weight centered properly so they don’t tip badly forwards or backwards. Here’s Mike on the bridge, making it look easy. Notice that the waist strap on his pack is unbuckled and hanging loose below it. That’s in case he were to fall and end up in the river – he could quickly wiggle free from the pack and swim ashore. People have drowned in rivers when they couldn’t get free of their pack and were pulled under and drowned, as happened to a friend of mine while trying to ford a river in Alaska.

The trail stayed level for a while, then climbed steeply, at times very steeply, up through the forest. It was hot, steady work and a few hours later we broke out of the trees and came to some tiny lakes at around 4,500 feet. We were glad to have the trail, though, as it saved us having to bushwhack. Here is a photo I took from the east shoulder of the mountain. We are looking northeast across the top of Stave Lake. The logged area in the top center of the photo, below the snowy peaks, is the drainage of Roaring Creek.

We were traveling light. Ice axes but no crampons or rope. The little we’d been able to learn about the climb indicated that there was no rope needed. Light packs, light sleeping bags, a bit of food, no stove, no tent.

The route seemed pretty straightforward, over excellent rock and then a snowfield which was pretty steep for a bit. This next photo was taken at around 6,200 feet.

More rock, including a couple of gullies with nothing worse than Class 4. We didn’t really know anything about the climb itself before we came here, but didn’t have any problems with route-finding. I know I’m skimming over this pretty quickly – in actual fact, from the little lakes to the summit was a full 2,000 vertical feet of climbing.

Here’s a look towards the summit taken late in the day.

As the climb progressed, the excellent weather started to deteriorate. Clouds started to form. We could see an antenna ahead, and a tiny shack.

From the hut, it was another quarter-mile along the ridge to the actual summit.

We passed a false summit, then on to the true summit by 7:45 PM.

In the swirling mist, we could see down to the west summit of Robie Reid.

I managed a few more photos before we lost all visibility. Here’s one looking down the east ridge.

And here’s one to the north. You can barely see the dark summit of Mt. Judge Howay poking up through the gathering clouds.

A look to the southeast showed Mt. Baker. It’s the white one in the center on the horizon.

By the time we made it back to the shack, it had socked in completely. It was unlocked, so in we went. We spent a lousy night – the wind howled and did a good job of keeping us awake. The next morning, we slept in late. It was still socked in, and we couldn’t see squat. We moseyed on over to the summit again, but the visibility was near zero. By the time the clouds burned off enough to see our way once again, it was one o’clock in the afternoon. As we descended, it became a splendid blue-sky day. We took our time and carefully down-climbed the gullies, but other than that our trip back down the mountain went without incident. It was exhilarating, though, dealing with that 2,000 feet of snow and good rock, with views to die for. Here’s one of the rocky bits we had to deal with.

Here’s a view of the cirque on the east side as we descended.

Here’s another view of Roaring Creek as we descended.

Now that the clouds had lifted, we had this clearer view to the north.

The tall double summit is Mount Judge Howay. The big dark one to the right of center is Mount Kranrod.

And finally, this view to the south.

From the east shoulder, we are looking down Stave Lake into the distance. At the bottom center is a bit of Alouette Lake.

It was almost seven by the time we reached the lake-shore and found Tom waiting for us in the boat. He whisked us back down the lake to our waiting vehicle, and before we knew it we were back home that same evening.

Every time I return to British Columbia to visit friends and family, I get excellent views of Robie Reid from the Mission area and am reminded of that great weekend long ago. Here’s a telephoto shot I took of the mountain from 15 miles away in early September – it was a year of little snowfall, so the south side of the mountain, seen here, was mostly just bare rock.

I understand that now, the approach to Robie Reid has been made much easier. You are able to drive logging roads to a point between Alouette Lake and Stave Lake, almost as far north as the top of Alouette Lake. From there, a good trail drops down to Alouette Lake and connects to the trail that Mike and I took up the peak. That means that strong parties could do Robie Reid as a day climb. That’s progress for you.