In December of 1989, I was running around like a chicken with its head cut off, trying to bag as many peaks as possible before the year ended. More accurately, I was trying to finish climbing all of the peaks on the Arizona Mountain Ranges list, and I only had a few left to do. Fresh off of a climb of Mohave Peak in the Trigo Mountains, an exciting stealth climb on land controlled by the United States Army, I had traveled north to Interstate 10 and motored on for a few miles to the town of Quartzsite where I gassed up and phoned home. This was back in the day when you had to find a pay phone when you were on the road, as cell phones hadn’t been invented yet. That done, only 8 miles farther east took me to what they called the Gold Nugget exit.

This had me poised to climb a peak in the Plomosa Mountains. The name derives from the Spanish word plomo, meaning “lead”. Here, it more properly meant “leaden”. Back in the 1880s, a full century before my visit, there had been a site called Plomosa where early prospectors mined a considerable amount of lead. This mountain range was quite extensive, spanning 32 air miles north-south with the freeway bisecting it.

Back when I visited, nearly all of the range was included in BLM land. I see now that the part I wanted to visit has been included in what is called the New Water Mountains Wilderness Area. Here is the view looking south from close to the freeway.

As I say, in 1989, I could drive as far as I wanted, and that is what I did, all the way to the low saddle in the distance. Passing mines with names such as Gold Nugget, Belle of Arizona and Apache Chief, I had soon covered all of 8.5 miles along the road up Apache Wash, to arrive at a saddle at 2,540 feet elevation. The road was good all the way, with one tricky bit just before the saddle. My notes describe the spot where I stopped and camped as nothing short of spectacular. I had made good time, and settled in for a restful night.

Rising at daybreak, I headed northeast up a slope and quickly gained 600 feet. This photo shows that bit.

That put me on a gentle slope, just an easy walk, which stretched all the way to the summit. Here’s how flat that part was.

In only 51 minutes, I had gone all the way to Black Mesa Benchmark, left there by surveyors back in 1949.

There was a large cairn on the summit of Black Mesa, where I found a register and signed in. I was the 8th person to do so since Barbara Lilley had left it in February of 1987.

Among the good views from the top was this one, looking south to the Kofa Mountains.

Turning around quickly, I retraced my steps back to my truck – I had only been gone for an hour and 40 minutes. By the way, we were still using the old 15-minute map for this area back in ’89. I learned that this area, including Black Mesa, the high point of the Plomosa Mountains, had been included in the New Water Wilderness Area the very next year.

Now what? I knew that the next peak on my list was only 7.5 air miles away to the southeast. So close! Instead of doing the sure thing, which was to take the easy drive back out to the freeway, then around for many miles but all on good roads, I thought that I’d take a clever shortcut. The old 15-minute map I was using showed that I could continue south from my camping spot on the saddle and, after several miles, come out on the gas pipeline road which would take me easily to my next peak. It seemed like it was worth a try – just think of the time and distance I would save! After all, I had a 4WD Toyota with high clearance, so I should be able to surmount any problems I met along the way. My mind was made up – I’d try the road less traveled, and away I went.

I reset my trip meter to 0.0 and started off. The first part was south down a gentle slope, and that went easily enough. After 0.8 of a mile, I had dropped 165 feet and found myself at a wash. The crossing was bad, the road pretty torn up. At this point, the map showed the road as 4WD, and it definitely was. It climbed over a gentle rise, then dropped a bit and followed along the north side of a wash, now heading west and passing by a number of old mine prospects. At 1.4 miles, it turned south and crossed another wash. The road vanished in spots, but I managed to keep going. It stayed on a level course to the southwest to 1.8 miles, then climbed up a ridge heading southeast to top out at just over 2,600 feet, higher than my campsite I had left behind. At 2.0 miles, the road went south, dropping again, but now it was on the side of another ridge. The road was slanted off to the right, and I was fearful of tipping over many times. 2.5 miles saw me turning west and down the spine of another ridge, then turning southwest to continue along the ridge and over a few of its bumps. The map showed this as a “jeep trail”, which is the next level worse than 4WD. More sidehills, more ridge, then at 4.0 miles I had dropped down to another wash. Once across it, the terrain leveled out and I was beyond the worst of it. My notes on the map said things like “bad”, “all bad” and “I won’t do it again!”

From this point, the desert was pretty flat and there were no more difficulties, but as I continued northwest, there was a myriad of confusing roads. I ended up following the trail of seniors in their ATVs and at the 17-mile mark, I was back out at a paved highway. Since I was already so close to the town of Quartzsite once again, I decided to head there and gas up. Lesson learned, not to be so cocky about second-guessing unknown back roads and instead go for the sure thing.

I headed back south on US Highway 95 and soon came to what was signed as Crystal Hill Road, which I followed east. After a few miles, it passed north of the Livingstone Hills and became the gas pipeline road. It was a good road, and I could easily do 30 on it. Along the way, I met up with an employee of El Paso Natural Gas – we sat in our vehicles and ate lunch and talked. Moving on, about 18 miles east of the highway I came to New Water Pass. Now I need to mention something important.

Back in 1989, I was still using the Vicksburg 15-minute map for coverage of this area. The area of the New Water Mountains was clearly labeled on it, and it showed the range high point as Peak 2536. I drove 2 miles east of the pass and parked. It was a short walk north to the peak, requiring only 38 minutes to the top. There, I signed in to another register left by Barbara Lilley eleven years earlier. As far as any of us knew, that was the range high point and we all climbed it with that understanding.

Fast-forward to March of 1994. The USGS was replacing all of the old 15-minute maps with the newer 7 1/2-minute maps. Not only did they have much better detail, but in some cases, labels of features had changed. That was what happened with the New Water Mountains. The name of the range was now clearly shown as applying to many more peaks, and as soon as we knew of this change, those of us who cared about such trivia headed back out to climb the “new” high point, which was higher than the one we had climbed years before.

My wife Dottie and I drove 200 miles from Tucson and took the Hovatter Road exit from Interstate 10. It was an easy run southwest down to the gas pipeline road, and another dozen easy miles west along it to where we parked. Just north of the road is where we camped for the night. There were a few light sprinkles, but nothing to dampen our spirits, and the next morning we awoke to blue skies.

We made a beeline for the peak, which was plainly visible in the distance at a bearing of 028 degrees. The desert here was quite flat, and aside from a few minor washes, we had a straightforward trek for about 3 1/2 miles. At this point, we had climbed about 650 vertical feet to reach a saddle to the northwest of the peak. Dottie decided to wait there for me while I scrambled up to the summit, another 400 feet. I signed in to the register left by previous climbers, then headed back down to Dottie. It was an easy walk back down to the desert floor and back out to the pipeline road. So there it was, the new, true high point of the New Water Mountains had been climbed, Peak 2839. Here are some pictures that will show you details of that climb.

This first one shows the saddle itself.

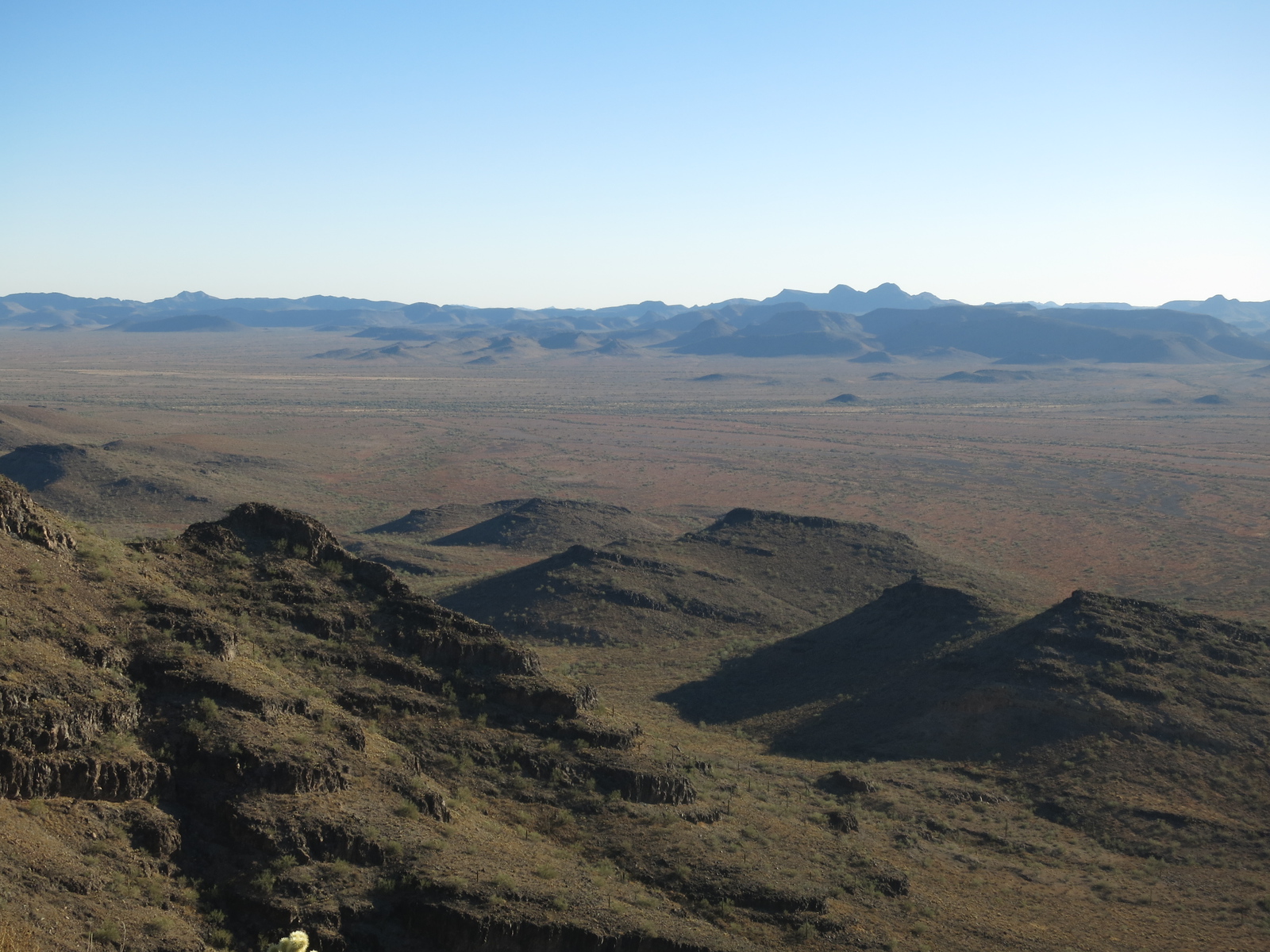

This next photo shows a view to the south, across the Ranegras Plain. Dottie and I had started walking from a point out there in the middle of the plain.

All of the excellent photos used in this write-up so far have been courtesy of Scott Peavy – many thanks to him for that. So let’s go back to the time period of the original part of this story. It was December 5th of 1989. I had just finished climbing the “original” high point of the New Water Mountains. Continuing east along the gas pipeline road for just over 5 miles, I then turned south on what is nowadays known as the Kofa Manganese Road. This road describes a path between the Kofa Mountains on the west and the Little Horn Mountains on the east, and after 9 miles of easy driving I parked just below Red Rock Pass at around 2,300 feet elevation. Heading straight east, I wrangled my way up through a forest of teddy-bear cholla cactus and reached the summit of New Water Benchmark in 51 minutes. I signed in to the register left by Barbara Lilley 2 years earlier. I descended a different way to avoid most of the cholla, and by the time I reached my truck it was already in shadow. Here is a photo Scott Peavy took of that west side.

This area was still covered by a 15-minute map at the time, which left some doubt as to whether that peak was actually a part of the Little Horn Mountains. Just to be sure, most of us climbed it anyway. When the 7 1/2-minute maps came out, they clearly showed it to be a part of that range. However, there was a peak farther east which most of us went after just to cover our bases, and that is what I’d do next. I drove back out to the pipeline road and camped there for the night.

The next morning, a quick drive of about 4 miles east on the gas pipeline road took me to Hovatter Road, an excellent track which I followed for 11 miles south and then parked. An easy climb of 400 feet took me to a flat mountain-top which I then followed for 4 miles to the east. It was easy going, with a gain of another thousand feet, but there were many smaller bumps to cross en route. It was a cool, windy day when I topped out on Little Horn Benchmark, where I signed in to yet another Barbara Lilley register left almost 6 years earlier. Here’s an old photo I took on that day, showing how flat the mountain is as we look to the west.

Over 30 years later, I returned to the Little Horn Mountains to make a clean sweep of every peak in the range. One day, I snapped this photo of the benchmark as seen from a nearby peak to the northeast.

Anyway, once done climbing this one, I walked the long, flat mountain-top back to my truck. It was time to move on, after having climbed the high points of the Plomosa, New Water and Little Horn Mountains. Everything was going well, but now it was time to move on and seek out summits in other ranges.