Jim Malusa, a botanist from the University of Arizona, had told me about some pictographs he had found in a remote canyon. This was an exciting bit of news for a couple of reasons – I had never before seen a real pictograph, and they were in a location that I had almost visited before. When I say “almost”, I mean that I had walked very near them without knowing that they were there. The urge to go and see them was very strong – Dennis agreed, so we planned a trip.

The first definition of pictograph that I found was as follows: “an ancient or prehistoric drawing or painting on a rock wall”. Bingo! That’s all the definition we needed, as it was spot-on – that’s exactly what Jim had found. Pictographs were, in fact, the earliest known form of writing, having been discovered in Egypt and Mesopotamia from before 3,000 BC.

I suggested an early start, and Dennis suggested an earlier one. He was more realistic than I – we agreed to leave at 4:45 AM. By the time we’d driven 85 miles on the freeway, morning had broken. On ever-worsening dirt roads, we headed in to the back country, eventually putting the truck into four-wheel-drive and crawling the last few miles in the lowest gears. It had taken us over an hour and a half to drive the last 15 miles, that’s how bad the road became. The hard part was over – now we could begin to enjoy ourselves.

The weather was perfect, nary a cloud in sight. The predicted high temperature for today was a mere 85 degrees F., pretty darn comfortable for a day in the desert. Three quarts should about do it for a short outing like this, plus a few snacks. We set out on foot, and soon found ourselves in a canyon bottom. In places, it was sandy and the going was easy, like this.

Jim had suggested following it upstream to be sure to find what we were looking for and so that’s where we stayed. Nearby mountains towered above us as we burrowed deeper into our canyon.

There was some modest bushwhacking and a bit of boulder-hopping as our path twisted and turned – it slowly gained elevation as we went.

At times we passed beneath dramatic cliffs, and we kept wondering what we’d find around the next corner.

It didn’t take all that long before we turned one last corner and found ourselves in an amphitheater surrounded by steep rock walls. Immediately we recognized the spot – it was just as Jim had described. At the base of one of the cliffs was a cave, about 30 feet long and maybe 15 feet deep. It was a curious thing, this cave – its walls were rounded, like a large bowl, and its roof was overhanging. There was no way that water cascading down the smooth cliff above it could enter the cave and run down its walls, so whatever was on the walls should remain undisturbed indefinitely.

One of our goals was to photograph whatever was inside the cave. However, when we arrived, we felt that if we waited another hour or two the sun angle would have changed enough that we’d have better results, so we decided to spend some time exploring the area. We were curious what was farther upstream from the amphitheater, so we needed to climb above it. A bit of looking, and we found a ramp which conveniently led up one side of it and took us to a flat area.

I’ve used the term “upstream” a few times so far, but I need to explain. For those of you who don’t live here in the Sonoran Desert, the word might be a bit misleading. There are 2 times of the year when we have rain: one is during our summer monsoon season, when typically we will enjoy thunderstorms which can drop a lot of rain in a short time, and may be quite violent; the other is during the winter, when rains usually last longer and are more gentle. Monsoon rainstorms can cause flash flooding, and otherwise-dry stream beds can become raging torrents within minutes – one of these can sweep away people, vehicles and even buildings, and if you’re not paying attention these can kill you. What I’m getting at is that 99% of the time, our watercourses are bone-dry, as was the case today.

As we walked up the stream bed, something caught our eye right away. On a rocky slope above it was a small antenna, which of course we had to visit.

Mounted on it was a box with a sign – I’ve seen a lot of curious things in the desert, but this was the first time I’d seen one of these. Bats are afforded a lot of protection in these parts, so it felt good to see that they were being studied in this way. The sign said that this was a “bat acoustic data collector”.

Even more obvious than the antenna, though, was something else nearby, a few feet away in the stream bed. Scattered about in our desert are naturally-occurring pools of water called tinajas, where water collects after a rain, usually along a rocky stream bed. These are crucial for the survival of wildlife.

Sometimes, though, agencies that care about these animals will “enhance” some of these spots – a little rebar and concrete can go a long way towards impounding more of the water. This creates even deeper pools, which can last for months after the last rain. Look at this next picture. To the left of the greenish water is a white strip, which is concrete. The water backs up behind it, on the upstream side to the right.

Along a rocky watercourse such as this one, any rain that falls will run into the bed and into these tinajas, or collect behind these little dams. There was quite a collection of pools here, a testament to how well this all works.

A motion-sensor camera with infrared capability was mounted near one of the pools – those government folks were curious about what animals (and even people) were making use of the water.

Here’s a picture of how it is all laid out. See the camera, just above the pool, on the left side of the dark circular rocky patch?

Upstream from these pools is an area of about one quarter of a square mile – any rain that falls in that basin and does not soak into the extremely thirsty desert soil will run right past here and help replenish the pools as well. Our map showed a naturally occurring spring nearby, and we found its location, but it was dry today – it may have been seasonal. Someone had spent time there, and had felt it was important enough that they’d built a concrete tank to hold water. An old rusted bucket and some lengths of pipe were mute testament to their efforts.

We made our way past the pools and back down into the amphitheater – it was time to try to photograph the pictographs. Here’s Dennis at the mouth of the cave – I’m up at the top of the cliff looking steeply down at him.

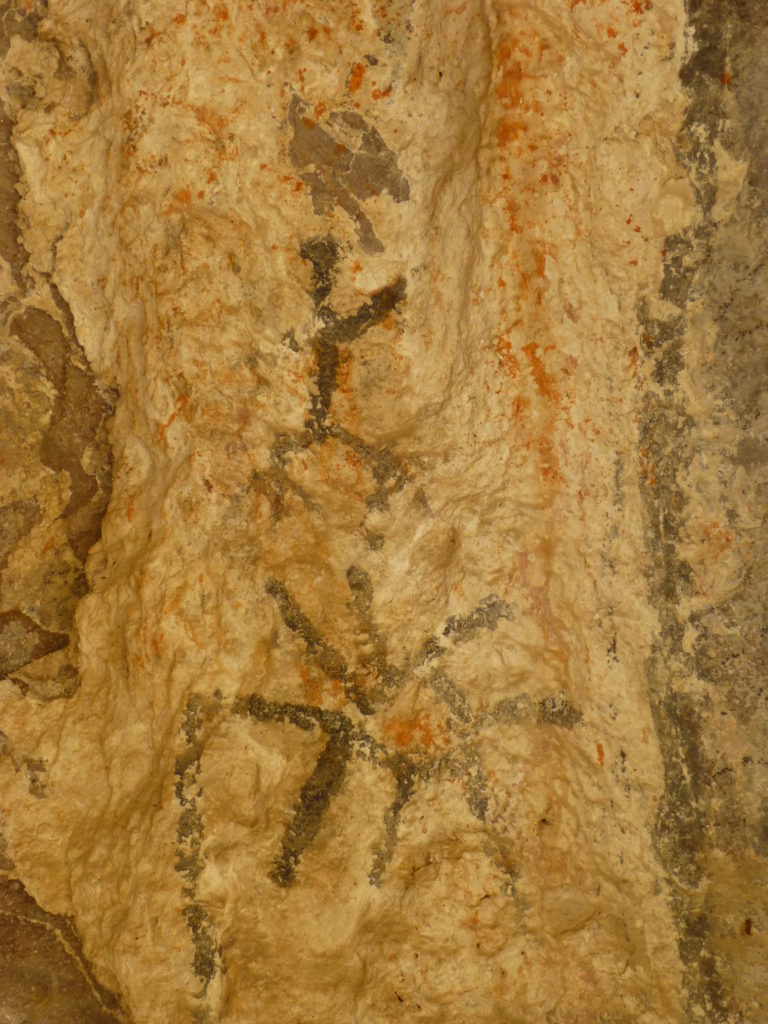

Once inside the cave, we had a good, long look at the drawings. I don’t know the significance of any of them, but you can use your imagination. I also don’t know their age, but probably several hundred years, and maybe much older. Here are a few close-ups.

And here are a couple of wider views of the cave.

This cave was a wonderful mystery, and we enjoyed our time there. Aside from taking photos to document the pictographs, there wasn’t much else we could do. After a while, we set off back down the canyon. Along its flank, we found a trail and followed it for some distance. It had obviously been enhanced by humans. I have come across many of these out in the desert. It likely existed in order to allow pack animals to move more easily into and out of an area.

It had been an easy day, and an enjoyable one at that, without a single mountain having been climbed. The location of these pictographs will remain a mystery in order to protect them, so I hope you can indulge me that.