Day 5 dawned on my March trip to southwest Arizona, where I had been climbing peaks in the Tinajas Altas Mountains and the Gila Mountains on the Luke Air Force Range. It was another perfect day with nary a cloud in the sky, and I was excited to cover some new ground. Three climbs were on my agenda, and to reach them I’d have to drive a mysterious road about which I knew absolutely nothing. The few desert travelers I’d met along the way hadn’t been able to share any information with me, as none of them had taken that path. No worries – I’d figure it all out as I went.

It was 6:30 AM by the time I drove away from my impromptu campsite. The first mile, I had traveled the day before, and it was easy enough, but then the road worsened as it passed through rolling country, the western foothills of the Gila Mountains. As the road dropped down into one wash, then another, things became rougher and the truck did a lot of bouncing around. I didn’t think much about it, as roads like that can be the norm in the desert. In short order, I reached a junction with another road. This was the one I’d been looking for, shown on the military map of the area as the Dripping Springs Road. I turned east on it and motored on.

The first quarter of a mile was fairly flat and smooth, and didn’t require much attention. But things gradually worsened, slowly but surely, and before long the road surface was littered with rocks, making for rougher travel. There were some particularly bad spots as I dropped down into, then climbed out of, a couple of steep washes. By the time I’d traveled 4 miles from my campsite, I pulled over on to one of the few spots where there actually was room to do so, where I wouldn’t be blocking the narrow road. My GPS had shown me that I was as close as I could be to my first peak. I could see it rearing above me – hmmm, didn’t look too bad. When I stepped out of the truck and walked around to the back of it to get my pack, I received the shock of my life!!

Somehow, in all of the pounding the truck had taken on the rough road, the tailgate had popped open. I need to explain that my Toyota is an ordinary pickup – it has a short bed, with a tailgate. On top of the bed of the truck sits a fiberglass shell, something I can lock when needed, and it also serves as a place where I can sleep. Once the tailgate had popped open, any time I was pounding my way uphill, gravity and the bouncing would funnel my gear to the rear of the truck and out it would fall on to the road. I had no idea this was happening as I drove, because my full attention was focused on white-knuckling along, simply trying to stay on the rough road and arrive at my first peak while I kept checking the map.

When I realized what had happened, it was like a gut-punch. All my stuff was gone. The only thing that remained was my sleeping bag and pad, and they too were on the verge of falling out. This was a devastating blow. Unless I could get all of my gear back, my trip was over. I turned the truck around and started back down the road the way I’d come. The first items I found were a hundred yards down the road – my lug wrench, and a cardboard box which had held bottles of beer. Sadly, a few of the bottles had broken – I carefully gathered up the broken glass, along with everything else and put it back in the truck. On I went, keeping a sharp eye out for any other of my belongings. Next, I found a plastic milk crate and the 6 gallon jugs of water it had held, most of which were still intact, but scattered over a small area.

On I drove, occasionally finding bits and pieces of my gear – a box of food; my mountaineering boots; a bag of trash which I’d been accumulating for days. About 3 miles back, I hit the mother lode. On a steep uphill stretch sat most of my things. Another crate of water jugs; my large cooler, upside down and its contents strewn about; a box of items which I always carried – wrenches, a tow strap, things like that which could be handy for minor truck repairs – which was strewn about; a box of glass climbing registers; my day pack (finding it had been my biggest concern – it held my emergency rescue device, headlamp, compass, my first aid kit, spare camera batteries, gloves and balaclava, as well as other small but necessary items); my folding chair. I was relieved to find all of this, and although it seemed like everything was accounted for, I drove the final mile to the previous night’s campsite just to make sure (I didn’t find anything else).

Relieved, but still feeling rather foolish, I drove all the way back to reach the spot where I’d parked earlier for my first climb. By now it was 10:00 AM – three and a half hours had passed with nothing to show for it. I shouldered my pack and started out. This one looked pretty straightforward.

35 minutes later, I stood on top of Peak 1580, with no sign at all of any previous visit. There were some pretty good views from up there, such as this one down to Fortuna Mine.

Here is the summit itself.

As I was filling out a register, I heard a sound in the valley below. There, I saw 2 quads slowly making their way up the road – they stopped briefly at my truck, then motored on. I took this telephoto shot from up top.

When I got back to my truck, it was time for lunch. As I sat there in the shade, sucking down one of my remaining beers and enjoying some food, a rumbling sound was approaching. Before I knew it, 5 large quads pulled up and stopped in single file. The lead driver had his young son with him, and we started to talk. I told them that I was climbing in the area, and my plan was to continue east along the road, to drive all of it and come out on the other side of the range. He looked at my Toyota, doubt written all over his face, and said he didn’t think I’d make it. One of the other drivers came up, and the two of them agreed that the problem was not so much the steep, loose spots but rather the fact that the road was very narrow in spots and strewn with countless boulders. They stated that their quads had very high clearance (they did, even more so than my truck), but also really low gearing when needed, allowing them to crawl very slowly over obstacles. Their conclusion was that there was a slim chance I might make it, but it was gonna be a real challenge for me with that truck. By the way, they told me that they had all driven the road several times in the past, and I noticed that they were all wearing full-face helmets. All the while, I was thinking “How bad could it be? – I’ve driven some really horrific roads in the past and always made it through.”

They wished me well and drove away, leaving me pondering what awaited. I finished my lunch and packed up, this time making doubly-sure that the tailgate was firmly latched. With my transfer case in low range, I started out in second gear in 4WD, thinking “This isn’t so bad – in fact, it’s pretty good.” I spoke too soon. Within a hundred yards, I had gone around a bend and was shocked to see how rough the road ahead looked. Before I knew it, I was in my lowest gear and crawling along. There was a place or two where the road went into a wash, and the ground was so rocky that I couldn’t tell where it came out on the other side. At one particularly bad spot, I left the truck running and got out, walking ahead to find the road. When I did, I thought to myself “How in the hell can this be the road – nobody would drive this.” That was the first major obstacle – big rocks everywhere – I was shocked I made it through. Soon after that, while I was again walking ahead, I met up with all of the quads. The 2 from earlier were heading back down the road towards me, but had stopped and were talking to the 5 I had seen at lunch, who were still heading east uphill. They were a bit surprised to see I’d come that far, but cautioned me that it was gonna get a whole lot worse. That turned out to be an understatement.

Did I mention the wrecked vehicle I passed? Things hadn’t gone so well for that driver.

Or for this one, seen a while later.

And for this one too, even farther along the road.

I couldn’t count the number of times I had to get out and carefully check the position of my wheels as I prepared to drive between big rocks – if off by even an inch sometimes, it would spell trouble. There were other times when, on one side or another, being in the wrong spot would have scraped the side of the truck along a rock wall or a huge boulder. It was slow, precarious going. Whenever possible, I would drive over rocks rather than between them, but that couldn’t always be done. It was clear to me now why all of the riders had been wearing helmets – if you’d been flipped out of your quad on some of this extreme ground, you’d crack your head open like an egg.

Finally, up ahead I saw the 5 quads stopped at a high spot – this turned out to be the pass that marked the greatest elevation along the road, about 1,100 feet above sea level. By the time I had driven up a couple of switchbacks to the pass, they had moved on down the other side. I got out and took a look around, finding a couple of interesting signs.

These signs were out in the middle of nowhere, so it was a surprise to see them there. It had taken me 48 minutes to drive the 3/4 of a mile from my lunch spot to the pass, for an average speed of about one mile per hour. I could have walked it in less than half that time. Here’s a look back the way I’d just come.

It had been a real nail-biter up to this point, but I was encouraged that at least the rest of the drive would all be downhill. I’d have a gravity-assist, so it would have to be easier, right? Hah! No sooner had I started down the steep stretch from the pass than I realized that this was not going to be some pleasure cruise.

Looking down from the pass in the direction I was heading. It was smooth here, the rocks were just around the corner.

Now I was letting the truck crawl downhill in its lowest gear but riding the brakes constantly so I could manoeuver between the rocks. It didn’t take me long to conclude that you’d have to be delusional to consider the downhill portion any easier. If anything, it was more aggravating than the uphill portion to the pass had been. The downhill was much longer than the uphill. Again, there were places where the road seemed to disappear in the wilderness of rocks and I had to get out and walk ahead to make sure where it continued.

As I worked my way farther down the canyon, it turned north. My next peak would be right beside the road, and as I kept an eye out for it, something came into view. Could that be it? No way! In its upper reaches, it was the most insane-looking thing I’d seen on the entire trip.

As I pulled up to its base, I knew in a heartbeat that I wouldn’t even set foot on it. No wonder nobody had climbed it before! It didn’t break my heart to move on, putting it well behind me. Every time I thought the drive was sure to ease up, it remained challenging. Finally, the canyon opened up, and I was out! What a relief, like being paroled. I did climb one more peak that afternoon, an obscure little thing called Peak 1140. I left a register on its summit at 3:45 PM.

Once done, I drove a few more miles and camped near the feature for which the road from hell had been named. The following morning, I paid a visit to Dripping Springs. What had been done there was quite a feat of engineering, as these pictures show.

I didn’t find any evidence of a spring – it may have been seasonal – but it was obvious that all water collected here came from a tinaja which must fill from occasional rainfall.

Here’s the spot where the pooled water enters the pipe that goes to the tanks.

Once back at my truck, I drove out of the valley to re-join the main road. As I drove the last few miles north to leave the military range and was approaching a gentle knoll out in the open desert, something caught my eye.

I stopped for a look, and was delighted to find this. Someone had gone to a huge amount of work to create this Man-in-the-Maze, a traditional design from the Tohono O’odham Indian culture in Arizona. It had been lovingly crafted. All of the rocks had been brought there, as the local area had none. I walked the maze, and it took me right to the center.

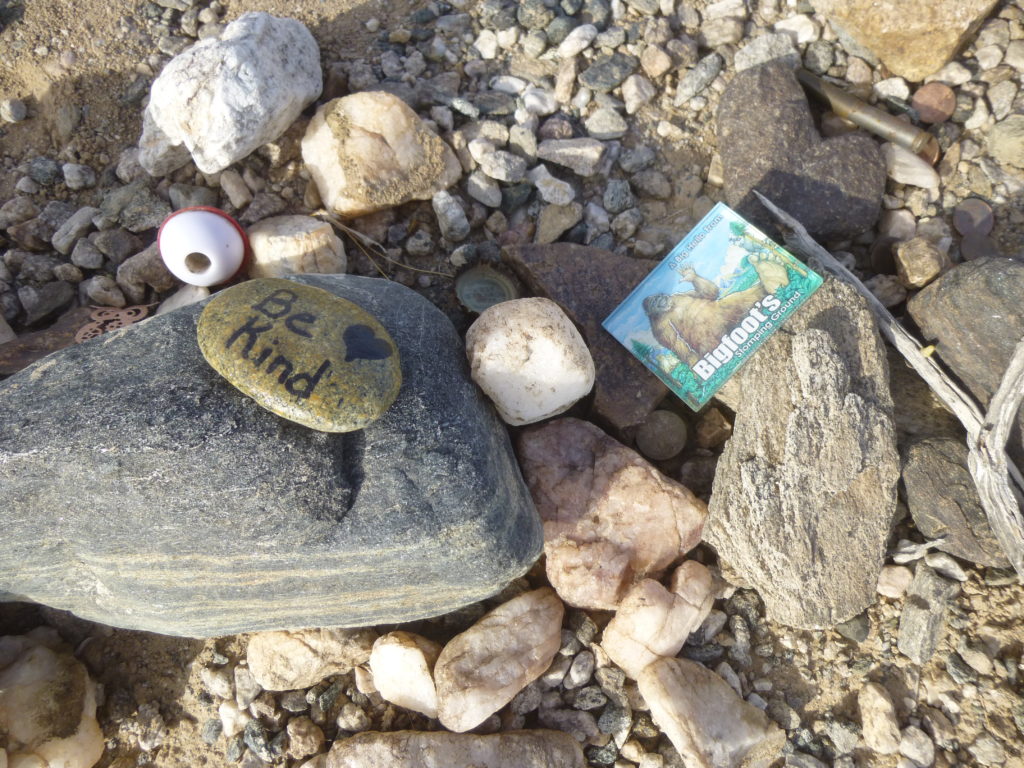

I then noticed the small items that had been left there by passers-by.

This next one was my favorite. It shows mountains, animals (probably deer and bighorn sheep) and someone riding on a quad. It was about 5 inches long.

My impression was that those who traveled the Dripping Springs Road, as I had done, left a memento there to mark their passing. For my part, I left some coins and a cap. Maybe this was a shrine, a place to give thanks for having driven the Dripping Springs Road and survived it! Here’s a look back to the mountains. You can’t tell much, but the road emerges on this side from the lowest point right in the middle of the photo.

All I can say is that I’m glad I survived it in one piece. Thankfully, not once did I ever hit the underbelly of my truck or the sides. But I wouldn’t drive that road again, in either direction, if you paid me. Thanks for accompanying me for the ride.