Many people who are not climbers probably think that it’s an activity that doesn’t change much. After all, you just put one foot in front of another and keep going until you reach the top, right? I’m talking here about alpine climbing as opposed to rock climbing. I got to thinking that the actual technique itself hasn’t changed, but much of the gear that we climbers use has changed a lot over the years. I’d like to reflect on that here.

It was in the spring of 1962 when I started climbing. The first few years were just on trails or old logging roads through wooded country, to the tops of various peaks near my home in small-town British Columbia. It wasn’t until the summer of 1965 when I first enjoyed the experience of actually climbing up into alpine country above tree-line. That did it for me, I was really hooked after that. Two summers in the Rocky Mountains, 1965 and 1966, afforded more opportunities to experience alpine climbing. It wasn’t until 1967 that I began to get serious enough to start buying some actual climbing gear that would allow me to attempt more difficult climbs and go on longer trips. Mountain climbers belong legitimately to the great unwashed, and it was in 1967 that I felt I had really joined their ranks.

That year, I bought my first set of crampons. They were the hinged type, made of steel and adjustable for different sizes of boots. By that time, most crampons were 12-point, the type that had 2 points aimed to the front (called “lobster claws”) – this was a big step up from the older 10-point type that had been used for a long time. Mine were 12-point and I used them for many years. I remember graduating up to rigid crampons sometime in the 1990s, which were meant for rigid-soled boots and better suited for more technical climbing.

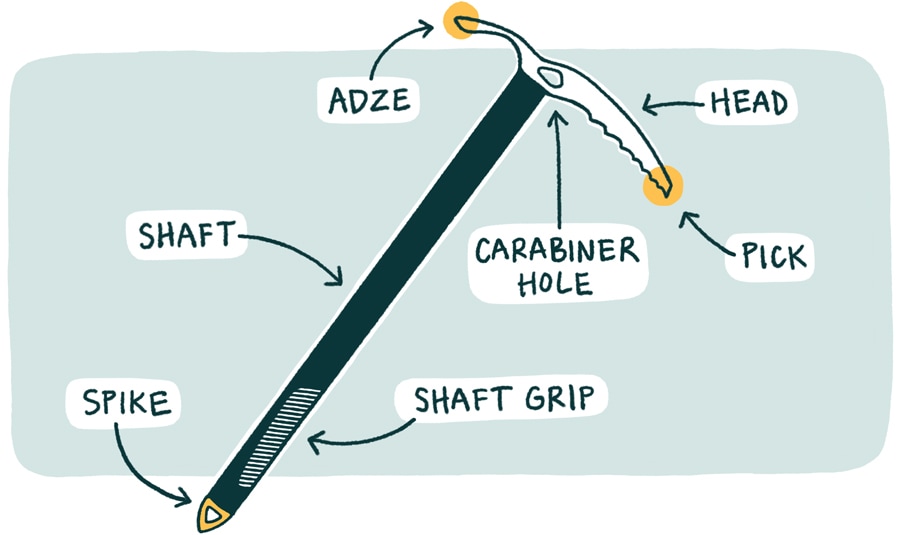

1967 also saw me get my first ice axe. It had an ash handle, and the pick came to a sharp point, needle-shaped (see figure 2 in the picture below – the pick sticks out to the right in the picture). It wasn’t until later years that somebody figured out that the pick could be made differently so that it would dig in better for self-arresting on ice, instead of the rather useless point that mine had.

Have a look at this next drawing. See the pick circled in yellow? See how the bottom of the pick sticks out farther from the shaft than the top of the pick? That simple change meant all the difference in successfully self-arresting on ice.

Some ice axe handles were later made of hickory, and even laminated bamboo was tried. They tried fiberglass as well, but they were heavy. After that, they started making ice axes that had metal handles, and as the years went by they made them out of lighter and lighter metals. My first axe had a handle that was too long for me – I used it for years until I finally got one that was the correct length, which also had an ash handle.

In the fall of 1967 I bought my first real pair of climbing boots. They were leather, had a full-length steel shank, were very rigid and heavy. Because of the steel shank, in really cold winter weather your feet really felt the cold. Back then, all such boots were European – mine were no exception. They were made by Galibier, and I had the Peuterey model. They were great for the most rugged and challenging situations, but for any amount of regular walking, they were real foot-killers. I can’t believe I used them for as long as I did – only after 10 days on Mount Robson in 1989 did I finally toss them.

Every climber I knew in the 60s and 70s wore wool knickers – they were de rigeur. The ones made by Woolrich were really popular. Mine came to just below the knees, and if you were going to wear knickers then of course you had to wear wool knicker socks. These came up to just above the knee, so that the knickers covered the top of the socks. Personally, I thought these worked great. Here’s a picture of a climber friend in 1976 wearing knickers, knicker socks and heavy mountaineering boots.

He’s also wearing short gaiters, which cover the top of his boots to prevent them filling with snow. We had knee-length gaiters for deeper snow. Gaiters became more sophisticated as the years went by, made of more rugged materials. I remember buying a pair of super-gaiters in later years, which were insulated for really cold climbing, and a nice invention.

In the wintry climbing conditions which we encountered for much of the year in British Columbia, it was important to keep our hands warm. In the above photo, Paul isn’t even wearing gloves – on that December 23rd day, it wasn’t that cold. If we needed some dexterity in the cold, we could always wear woolen fingerless gloves like these.

For colder weather, we wore woolen mittens (mitts are always warmer than gloves). Those of us who climbed in the 60s and 70s in the north will remember a condition which afflicted us all, something called “sardine mitt”. Those flat tins of sardines which you opened with the key that came with them were messy things. During winter camping, sometimes it was so cold you didn’t want to take your mitts off at all, especially if handling something metal like a tin of sardines. Inevitably, some of the oil in the can would get on to your woolen mitts. Those sardines from years ago were especially stinky, and you’d never get rid of the smell on your mitts.

The first item I ever bought from REI in 1969 was a pair of down-filled mitts – I paid 5 bucks for them. I present them to you here today. The palms are leather, and on the back is a large piece of mouton fur. Many years later, the industry invented Gore-tex overmitts to wear over any warm inner mitts.

Another thing that has changed a lot are climber’s headlamps. They used to use the old-fashioned flashlight bulbs, which were pathetically dim and would burn out from time to time (you’d have to carry a spare bulb or two). How far we’ve come with those! – the bulbs are so powerful nowadays, and seem to last forever. I can remember in the 70s when they first came out with lithium batteries, C and D cells – they were really expensive. Their appeal was that they were lightweight and re-chargeable, but as I recall they didn’t work all that well. Several years ago a friend and I tried an experiment with his new Chinese 10-dollar LED headlamp. One night, with 13 miles separating us, he shone it at me – I could clearly see his light even on the lower power of the 2 settings.

One important item of climbing gear that has not changed much, in my humble opinion, is the sleeping bag. The best bags always used down for insulation, and still do today. Sure, now they can treat down to make it less prone to failure if it becomes damp, but at the end of the day, down is still the best fill. Synthetic-fill bags are also popular these days, and that’s a new development in the last couple of decades, but when you look at warmth-to-weight ratio, the down bag wins every time. Forty years ago, I made a major investment in a top-quality sleeping bag with 850-fill down. That’s extremely high quality, and it means one ounce of down takes up a space of 850 cubic inches. I paid $500.00 for the bag, and I just sold it to someone else for more than that all these years later. Good bags have become very pricey, and it’s easy to pay over a thousand dollars for a top-quality expedition-worthy one these days.

Tents have improved with the use of high-tech fabrics and construction, but even back in the day there were some pretty good ones. A severe storm and a heavy snow load can still destroy the best of them, though – they aren’t infallible.

Backpacks – now there’s an item that has gone through a lot of evolution. I remember as a Boy Scout the old Trapper Nelson backpack in the 1950s, but they’d already been around since the 1920s. Primitive but functional, they were just a wooden frame with a canvas bag to put stuff in and a pair of straps so you could wear it, but they were so uncomfortable. The next step was to go to a metal frame (usually aluminum to keep the weight down) and a nylon bag with pockets and compartments. They had external frames, though, which nowadays we look back on as being awkward and oh-so primitive. The next huge step forward was to put the frame on the inside of the pack, so it couldn’t hang up on things when you were bushwhacking. That development occurred in the 1970s, and when I bought my first internal frame pack from Synergy Works in the Bay Area, I though I’d died and gone to Heaven. Internal adjustable frame, with pockets you could snap on and off as needed, rugged material – wow! In all the years since then, backpacks have become lighter but at the expense of durability. The same goes for day packs – many now are as lightweight as can be, but I wouldn’t give you a bucket of warm spit for any of them when it comes to enduring a good bushwhack. I’ve had day packs made of canvas duck that lasted for decades and weren’t all that heavy. Were they high-tech? – nope, but I never did wear them out. Lost them, grew tired of them, gave them away, but never wore them out.

Assuming you want to boil water or cook food while on your climbing trips, you’ll need some kind of mountaineering stove. Back in the day, we had stoves that attached to fuel canisters. Then along came a company called Mountain Safety Research (MSR) and revolutionized the industry. They became famous for a small stove they made which could burn white gas, diesel, gasoline or kerosene, making it usable anywhere in the world. In the 40 years since then, they’ve expanded their offerings to include many other models.

If we’re just talking about backpacking stoves, they fall into 4 basic categories, depending on what type of fuel they burn. We’ve got alcohol, wood, canister or liquid fuel. Each type has its pros and cons. For the last several years, I’ve used a stove that attaches to a fuel canister, the fuel being a butane/propane mixture in a self-sealing canister. I’ve used this stove not only for backpacking, but also for every car-camping trip I go on. My stove is only 3 inches tall and weighs a mere 3.3 ounces. Even better, you can buy one on Amazon for $13. Here’s what it looks like when attached to a fuel canister. (This is a large canister, you can also get them half this size).

Climbers often ply their craft in foul weather. Before the mid-1970s, it was hard to stay dry in rainy or snowy conditions without getting soaked from your own sweat inside your rain gear. Then along came Gore-tex, a revolutionary product that was touted as being both breathable and waterproof – it would let your body moisture escape through the fabric while keeping the rain out. Around 1977, I bought my first set of Gore-tex rain gear, pants and jacket. It got plenty of use, but I didn’t think it worked all that well. As the years went by, I think they improved the technology because later garments I bought seemed to work better. Using it in bivouac bags (bivi bags) was a boon to lightweight climbing trips. It’s even used in boots these days. Here I am on top of Cerro Aconcagua, elevation 22,835 feet, wearing a Gore-tex jacket and pants over top of a down parka and pants, and with blue Gore-tex overmitts.

I’m not going to discuss rock-climbing hardware here, which has seen vast improvements over the years, as I’m no authority on the subject. I’ll leave that to the experts. However, alpine mountaineers do use helmets, harnesses and ropes, and I’ll simply say that all of that gear has become stronger, lighter and better in every way.

In the 1960s, when I learned to climb, if you didn’t know how to read a map and use a compass, you could quickly find yourself in a world of hurt out in the middle of nowhere. The lucky few also had an altimeter to further help them. Orienteering was an essential skill, one which has faded somewhat into the background with the advent of modern high-tech devices. No single item has been of more help than the GPS device (Global Positioning System) – there’s a system of satellites owned by the U.S. government which convey to the hand-held device your exact position on the earth’s surface. It also tells your altitude, time of day, works as a compass, remembers the track you’ve walked or driven, and much more. GPS may well be the most significant improvement in climbing history.

A close cousin of the GPS device is the satellite messenger, a type of rescue device. You buy the unit and pay a fee to subscribe to a service. That fee allows you to tell your contacts exactly where you are at any time, to engage in 2-way email communication with them, and to send out an SOS call for help to rescue services if needed. Since I’ve always done most of my climbing alone, I carry one of these devices with me every time I head out into the mountains. They can be used anywhere on earth, unlike cell phones which may have spotty or no coverage in many places.

I’ll bet you’ve never heard of Kendal Mint Cake. In the 70s, when I was climbing in B.C., we sometimes carried it as an energy snack. It was made in England, and was nothing more than a hard bar of sugar and glucose flavored with peppermint. Energy foods for climbers have come a long way since then, with a bewildering array of goos, gels and other items that are meant to give you just the right kind of energy boost at the right time. The same goes for drinks – many now exist that purport to replace vitamins and minerals lost in the exertion of climbing. Lots of choices that didn’t exist in years gone by.

That’s it, folks, just the ramblings of an old-time climber thinking back on some of what has changed over the years. It’s a lot, actually. How we climb is still basically the same as it always was, it’s just that all the stuff we use to do it has definitely changed in ways that make it safer and more comfortable.