Sometimes it takes me a while to get started on a story – I need to be in a certain mood, and if I’m not there – well, it’s like anything else, if you’re not in the right frame of mind, the words don’t come. I’ve ruminated on this one for a while, but I think I’m ready to start now. It’s a story about a climb I did this winter out in a remote part of the desert, but what’s important about it is which part of the desert. Here in Arizona, we have a lot of desert, and there are various entities that have jurisdiction over different parts of it. Here are some of them: state trust land; Indian reservations; BLM (Bureau of Land Management); national parks; national monuments; military reservations; land which is owned by an individual or company, like a mine; national forests. I’m sure there are others I’ve missed, but you get the idea. Pretty much anywhere you go, somebody has a say in how that piece of land is managed. I think that, of all of them, the most restricted would have to be land administered by the military.

It might surprise you to know that Arizona has about 3.5 million acres which are controlled by the military, more than almost any other state. We have land that is run by the Army, the Air Force, the Marines and even the Navy (yes, the Navy, here in Arizona!) Personally, I think that the Army exerts the tightest control over their land when it comes to allowing civilians to enter. The big Army base at Fort Huachuca does allow civilians to visit parts of the base with a permit, but the Yuma Proving Ground in the southwest corner of the state is a different matter. There, they don’t issue permits, so its 1,300 square miles is pretty much off-limits to the public.

I had my eyes on a remote peak, one that had been visited decades earlier by 3 different parties. I’m not sure how the first ascender had gone in there, but the second ascent had been done by a friend who had driven as far as allowed, then used a bicycle to get much closer, finishing the climb on foot. The third ascent had been done by a group I knew who did the whole thing on foot, no bikes, for a total round-trip distance of about 22 miles in the one day. The curious thing about this peak was that its summit sat just 2,000 feet outside of the Army’s land, but to get to the peak nearly all of those 22 miles had to be done across forbidden Army territory which was closed to the public, no exceptions.

One afternoon I drove north from Yuma along U.S. Highway 95 for 54 miles, then started east on the King Road, a good dirt road which took me into the Kofa National Wildlife Refuge. This was a wide, well-graded road – you could safely drive 40 mph along it, and in about half an hour I had covered just over 13 miles of its length. This brought me to a major intersection of dirt roads: one turned left (north) to go up to the King of Arizona mine and the Kofa Mountains (the range is named after the mine); the other continued straight, and today that was the one I wanted. Climber friend Dave had been this way before and spoke of the road worsening after this point. It did, and in the next 5 miles I had to cross through 13 minor washes, none of them problematic. He had also said, though, that beyond that point it got progressively worse and he wasn’t kidding. The next 4.4 miles headed straight south, and I was traveling across the grain, meaning that all of the drainage from the Castle Dome Mountains headed east and directly across my direction of travel. Dave says that this makes the drive “a bit tedious” – that’s an understatement! In those 4+ miles, I crossed a total of 151 washes, or dips in the road, each of which would cause a prudent driver to either put on the brakes or shift to a lower gear while crossing them. I’d say you could do it all in 2WD, but high-clearance would be helpful for many of them.

It was late afternoon, almost sunset, by the time I reached the end of the road. Okay, it wasn’t actually the end of the road, but sort of. Another road branched off to the west, and although I didn’t follow it, if you did, in just over 5 miles it would take you to something called the Keystone Mine. This was a small silver mine, active the better part of a century ago. If you went another mile, you’d arrive at the end of the road, at what is shown on the map as Chain Tank, a water-hole for wildlife.

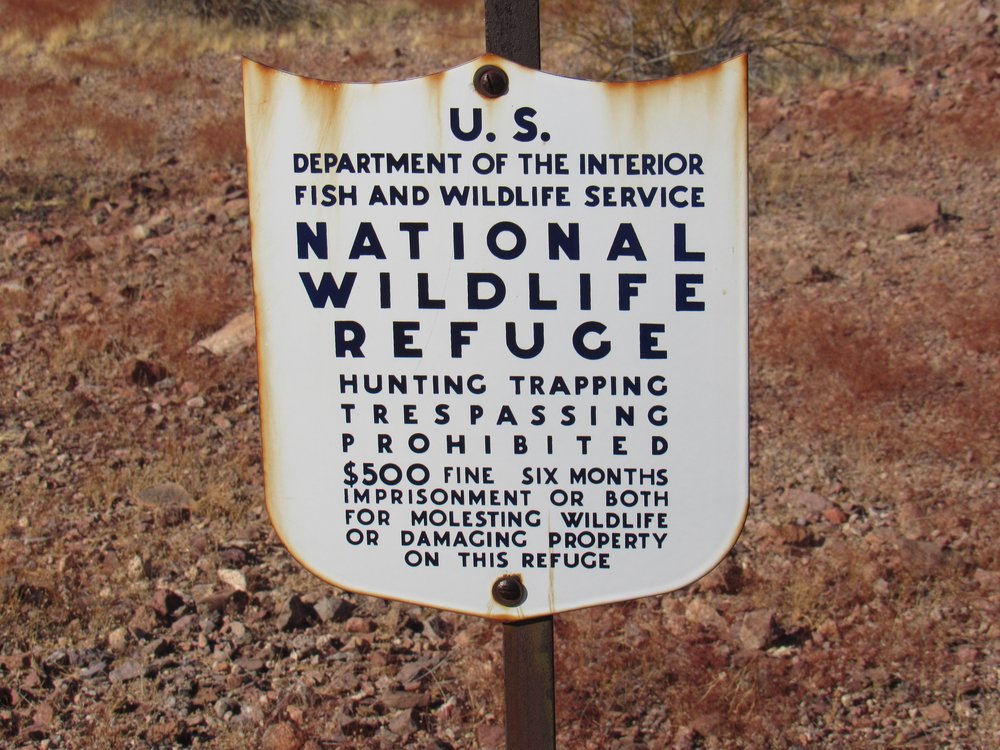

My plan was to camp there for the night and, early the next morning, head south to my peak. The road did continue south, but this sign stood there.

That was okay, as I had my mountain bike with me – my plan was to use it to cover many of the miles separating me from the peak I wanted to climb. I settled in for the night, but as the hours passed, I got to thinking more about all those miles. There were roads from where I was camped all the way to within just a couple of miles of my peak. Even using the bike would be time-consuming and tiring. Hmmm, let me think about this some more.

Morning arrived. As I lay there in my sleeping bag waiting for the risen sun to warm things up a little, I made a decision – I would drive beyond the sign. The area beyond it wasn’t technically part of an actual wilderness area, I guess they were just letting the road fade away and be reclaimed by the desert. I packed everything up, and stashed my bike inside the shell of the truck along with all my other gear. So as not to appear too obvious, I drove down the side road for a quarter mile and then followed a faint track that connected with the “closed” road some hundreds of yards beyond the sign. That way it wouldn’t be obvious to anyone that I had chosen to drive the “closed” road.

Once I started driving along the closed road, I was struck by how good a condition it was in. It appeared to not have been driven for a long time. Here’s what it looked like – you can see my faint tracks on it. The road was so good, in fact, that it was obvious that at one time the Army had used this road and maintained it, and not the wildlife refuge.

It was the work of only 15 easy minutes to drive this road for 2.3 miles, at which point I came to the actual boundary of the Yuma Proving Ground.

I could tell that the road beyond the sign, which was on Army land, hadn’t been driven for many years. This emboldened me – if nobody was driving on it, maybe I could, and get away with it to boot. My decision was made, and away I went, driving farther south on the good road into the Proving Ground. I have to confess that I was more paranoid beyond the signs. In less than a mile, I was in for another surprise. What to my wondering eyes should appear but the mother of all roads. Almost 30 feet wide and graded so smooth you could play pool on it, I was shocked – I wasn’t expecting anything like that out there. The road I’d been on merged with this one.

Now what? I had already driven over 3 miles of roads that I shouldn’t have, and now I stood staring at this beauty. Hmmm, what if I drove farther on this really good road? I knew exactly where I was, and I knew exactly how far I’d have to go along the road to best position myself for the climb – 5.1 miles more would put me right where I wanted to be. I had already been working on a set of cockamamie excuses I could use if the Army caught me, so I was feeling pretty sure of myself. What the heck, let’s go for broke! In for a penny, in for a pound, as they say. Away I drove, continuing south on this fine road, and I soon found that I could drive 30, 40 or even 50 miles an hour on it – the surface was amazing. It had been so well-engineered that even down through major dips like washes, you could still drive really fast. I figured that if I drove quickly, I’d be done with this really exposed and outrageous bit of driving really soon. Keeping my speed at 30 mph, I was done in 10 minutes. A major wash cut across the road, and that was where I turned off. I drove up the wash for a quarter-mile or so, then parked the truck in a well-hidden spot.

Wow, I had just broken every rule in the book, and had driven almost 8 1/2 miles that I would have had to do on the bike (17 miles round-trip). My parking spot was in as obscure a place as you could wish for, and I felt really comfortable about leaving the truck there all day. Now all I had to do was climb the peak.

It was already late when I started out on foot at 10:15 AM. The day could not have been better – blue skies and 65 degrees F., with a slight breeze. My start was west, and in just over a mile I came upon a sign which indicated I was now leaving military land.

A few miles ahead and rising 1,500 feet above me stood a remote part of the Castle Dome Mountains, bristling with peaks and as yet un-visited by climbers.

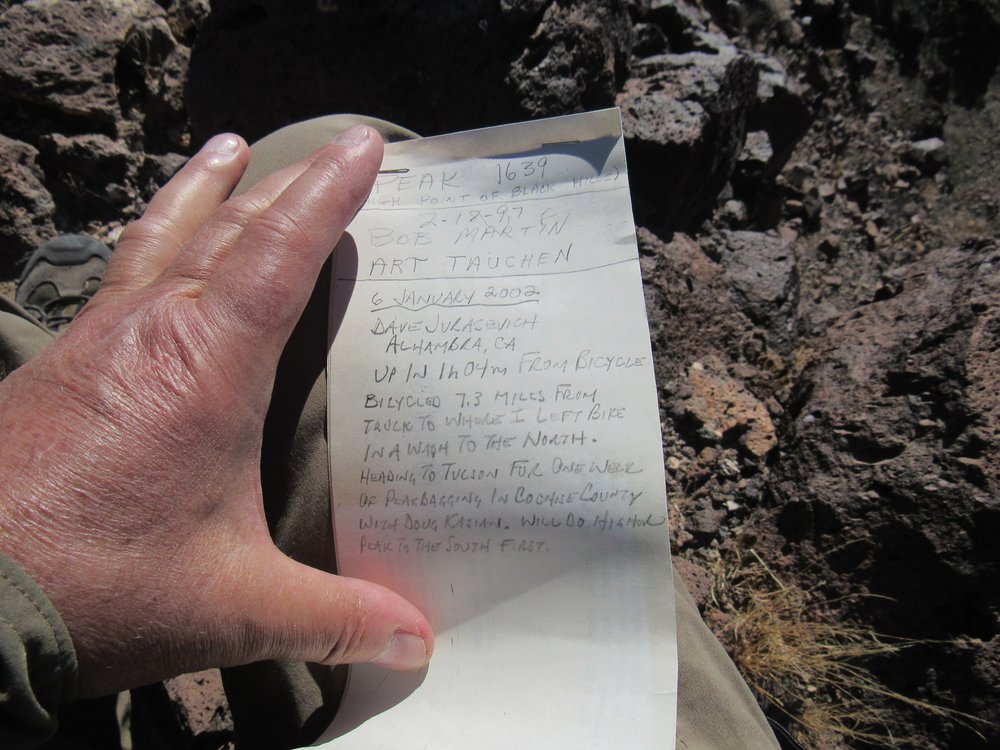

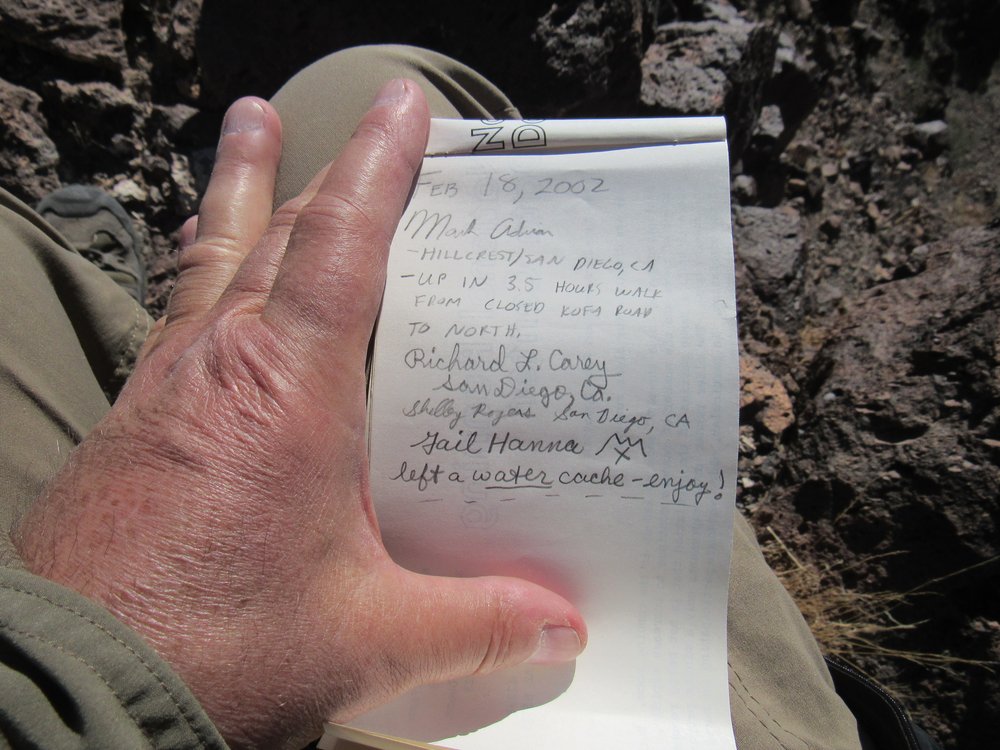

Time passed – I continued west, then swung around to the southwest; finally, to the south and up a different valley, reaching a saddle at 1,000 feet elevation. From there, 500 vertical feet directly up the north slope, where I made my only real mistake of the day. I ended up on the northwest ridge of my peak, and then found myself contouring around the south side of the summit for the last 150 feet and getting on to shaky ground. I was glad to finally pull on to the top of Peak 1639, the high point of the Black Hills. Wow, it had taken me 3 1/4 hours to get there from my truck, a terribly long time to cover 3.4 miles. Every climb tells me I’m older and slower. I found the register and made a note of the only others to have signed in.

While on top, I even managed a phone call home. I was pleased, but not too surprised – Verizon cell phone coverage is truly amazing. I’ve been able to place calls from the most impossible locations. I signed in to the register, then studied the lay of the land.

On my way in to climb the peak, part of my route had described a loop around a couple of other peaks, mileage that now, in retrospect (hindsight’s always 20-20, isn’t it?), I could cut off of my return to the truck by heading in a different direction over a couple of low passes. It involved more vertical, but less distance, and seemed like a reasonable trade-off. Here is the view I had to the north, looking over some of the path I’d have to travel. Once down off my peak, I’d end up right dead-center in the photo. In the upper part of the photo are 2 peaks: the one on the left is pointed, with white blotches on it; the one on the right is dark and flat-topped. My new path would go between the 2 of them. My truck was hidden on the other side of the flat-topped peak, behind the farthest right part of it.

Here’s a great view I had from the top of Peak 1639, looking west into the Castle Dome Mountains. Few of the peaks in this rugged and remote part of the range have ever been climbed.

My descent route was to the north, and although steep, it proved less troublesome than the northwest ridge. Before long, I was at the base of the peak, then traveling over the 2 passes. That done, it was an easy walk back to the truck, and I had saved myself a mile. Even so, I’d been out on foot for 6 hours. I snapped this poor photo of the peak I’d climbed back over the second pass.

It was a short drive back down the wash to the amazing Army road. Once I reached it, I headed north and drove quickly along it until I reached the junction with the lesser road, still on military land, and followed it north for a short distance until I reached the boundary of the wildlife refuge. The sun was setting, and this seemed like a good place to camp. As I said earlier, this portion of road hadn’t been used for many years, and I knew I’d have an undisturbed night if I camped here. As I thought more about things, I concluded that even that excellent road I’d driven a few miles back seemed seldom-used, my reasoning being that this was such an obscure and remote corner of the Yuma Proving Ground. I’ll bet you could drive it with impunity and rarely see any military vehicles on it, so the chance of getting caught there was very low. I did see a few signs, though, whose meaning escaped me.

This one was found lying flat on the ground, with a huge spike through the center hole pinning it in place.

My night spent on the proving ground was quiet and uneventful. I awoke the next morning to another beautiful Arizona day.

The scenery there was amazing, awash in spectacular peaks.

It was short work to pack up and continue north, where I soon left the military land and returned to the wildlife refuge.

I had this view of Castle Dome Peak, the range’s namesake, off to the west.

It had been a great couple of days, flying under the radar in a very special part of the desert. Highly recommended.