Be sure to read the previous 3 parts of this story before embarking on this one.

We left off after having stopped to look at the Grave of Eight, a sobering experience for sure. Back out on the Camino, we continued west. Beside the road, we saw this tree carrying large clumps of mistletoe. It’s proper name is Phoradendron californicum and it is a common parasite in the Sonoran Desert.

From this area of the Camino, we can look to the southwest and see the Sierra de la Lechuguilla. Only the northern tip of this range lies within Arizona; the vast majority of it sits down in Mexico in the state of Sonora, and the Mexicans call their part of it Sierra Tinajas Altas (not to be confused with the Arizona range called the Tinajas Altas Mountains, which we will soon meet). The Lechuguillas are steep, loose and rugged. The next photo shows another stretch of the Border Wall, running east from the Lechuguillas over to the Tule Mountains.

From the time we left the Cabeza Prieta Mountains near Tordillo Mountain, we entered the Lechuguilla Desert. This desert occupies the space between the Tinajas Altas Mountains and the Gila Mountains on the west, and stretches east over to the Cabeza Prieta Mountains and the Copper Mountains, an area roughly 8 miles wide and 25 miles long in the US. Lechuguilla is a generic Spanish name for agave, here Agave deserti.

At around the 87-mile mark, something major happens – we leave the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge. Our last 60 miles of travel along the Camino have been inside the refuge, but now we leave it behind.

By leaving the Cabeza, we enter the Barry M. Goldwater Range. – West. This western section of the range is controlled and administered by the US Marine Corps at Yuma.

Just over a mile later, we come to a a patch of lush vegetation, unlike anything we’ve seen in a long time. This is the head of Coyote Wash, but the wash is hard to detect, because the runoff here is unchannelized sheet flow. A bit south of here is the watershed divide with La Jolla Wash. Coyote Wash runs north and its waters eventually make their way to the Gila River up by Wellton. La Jolla Wash runs south, crosses the border into Mexico and eventually soaks into the sands of the Gran Desierto.

Ahead of us now rise the Tinajas Altas Mountains. Their high point, Tinajas Altas Benchmark, dominates the western skyline, rising 1,600 feet above the desert floor.

The road continues to the northwest, straight as an arrow, and if you follow it for 5.4 miles, it will take you right up close to the foot of the mountains. You will have to stop and park, and when you do, you will see this in front of you.

In the above photo, see the belt of vegetation running across near the bottom of the image? Right above that, in the middle, is a small patch of rock that is distinctly greyer than the rest of the rock – that is where we had to go. It wasn’t far, only a few hundred yards from where we parked. Allow me to show you more photos before I launch into an explanation of what we will see. In this one, we have walked up to the lowest pool.

Here’s a closer look into the pool. I don’t know how deep it is, but it looks pretty deep.

Now this is important – look at the rock above the pool – it is very steep and smooth.

A 19th-century surveyor of this area, David Gaillard, had this to say:

“Many of the early travelers and gold seekers made the journey in safety, but others, unused to desert traveling, their insufficient supply of water exhausted, realized their peril, and pushed toward Tinajas Altas. Some perished of thirst by the way; some wandered from the road and never found the water they craved; some reached the tanks, finding the water all gone and too weak to go further, lay down and died; others reached the longed-for spot, but in such a state of exhaustion that, unless water was found in the lower tank, they were too feeble to climb to the next and perished miserably, their horrors aggravated by the thought that water, for want of which they were perishing, was but a few yards off, had they but the strength to reach it…. Three prospectors, who, exhausted for want of water, reached the lower tank only to find that some travelers, who had preceded them but a day or two, had emptied this tank. Feeling sure that there was water in the next tank above, they made strenuous efforts to climb to it, but were too weak to succeed, and perished at the foot of the almost vertical slope leading to the second tank, where their bodies were found a few days later, the fingers worn to the bone in their dying efforts to reach the water, which was found in abundance in the tank which they had tried so hard to reach.”

Nine intermittent and perennial pools hold at least 22,000 gallons when full. Permanent water made these large tinajas “renowned in the pioneer history of the district,” according to Norwegian ethnographer Carl Lumholtz.

It can be easy to miss these natural tinajas if you don’t know exactly where to look. The pools are stacked one above the other, stretching over a vertical distance of 300 feet. I once climbed up to a few of the next higher ones by going around to the side, but there’s a lot of steep, scary rock to negotiate. If you were already dying of thirst and in a weakened condition, or afraid of steep rock with a lot of exposure, I can see how you wouldn’t make it up to a higher pool. It had rained heavily in this area only a few days before we arrived, so I’ll bet that all of the pools were pretty full. I’m glad we stopped, because these tinajas played such an important role in the area’s history.

Here’s Jake standing in front of an elephant tree (Bursera microphylla) off to the side of the lower pool.

It was approaching one in the afternoon by the time we left here, with a lot of ground to still cover. We had a choice to make. Many people just make a beeline from the pools straight north to the town of Wellton on Interstate 8 via the wide, smooth, dirt military road. It’s so well-maintained that you can drive it at 50 miles per hour without much effort, and it’s only 25 miles to go to reach Wellton. However, if you truly want to drive the entire length of the Camino del Diablo, you’re not done yet, not by a long shot. Since we had come out here to drive the true Camino, our choice was this next option.

About a mile north of the pools, the Camino makes a distinct turn to the southwest and travels through what is known as Tinajas Altas Pass. This route is quite flat with no elevation gain to speak of, and in just over 3 miles you pass through the rugged Tinajas Altas Mountains to emerge on their western side. This was quick work, and we found ourselves on what is called the Davis Plain. This is a really flat area covering many miles, and is actually a part of the larger Yuma Desert. This is one of the harshest areas you could imagine, with an average annual rainfall of only 2-3 inches, and summertime temperatures that routinely exceed 120 degrees F. Once through the pass, one of the Border Patrol’s emergency beacons is one of the first things you’ll see.

Here’s a close-up of the sign on the beacon.

The upper sign is quite sobering. It says: Attention! You cannot walk to safety from this point. You are in danger of dying if you do not summon help.

On the lower sign is a red button. The sign says: If you need help, push red button. U.S. Border Patrol will arrive in 1 hour. Do not leave this location.

These emergency beacons are scattered throughout the desert, and are strategically placed along the main paths that border-crossers travel. At night, a flashing blue light on their tops can be seen for many miles.

We continued north along the Camino, hugging the western side of the mountains for a while, then moving northwest at an angle that took us farther away from the range. After about 10 miles from the pass, we reached an important junction. The road had been a very rough washboard for several bone-jarring miles but it now smoothed out. Here are some of what we could see at the junction. One sign indicated a road that went northeast to Cipriano Pass, about 4 miles away. That pass went between the Gila Mountains to the northwest and the Tinajas Mountains to the southeast, and 4 miles beyond that it joined up with the “shortcut”, the super dirt road that went from the Tinajas Altas tanks up to Wellton. Our plan was to continue northwest along the Camino.

All along the west side of the road, the military had put up these signs – there were hundreds of them, leaving no doubt in your mind.

At least as far as climbers are concerned, the signs are telling you not to go over to the Butler Mountains. That range of low peaks sits just a few miles away to the west, behind the signs. It is a granitic range, with its slopes partly buried by drifting sands. Back in the day, you could drive right over to the range and climb its peaks, but I think that all changed after 2002. Nowadays, you have to sneak past the signs to climb them, and risk getting caught and fined, as happened to a couple of my friends in recent years. This range has become a serious stealth. Here is how they look from the Camino.

Once we leave that major junction, it is another 5 miles of northwest travel along the Camino until we reach the tip of Vopoki Ridge. It is said that this word means “lightning” in the O’odham language.

Vopoki Ridge is a western limb of the Gila Mountains. If you click on this link, then on the map, it’ll open a bigger map which will give you a good idea of the lay of the land. As we continue along the Camino, we see some military signage. “Leg Iron” – you’ve gotta love those cryptic military terms they use.

Here’s something else you see as you drive along the west side of Vopoki Ridge.

Looking off to the west from the road, you can spot Yodaville – this is a telephoto shot.

I love this next photo. We are looking southwest across the Yuma Desert to some peaks that are half-buried out in the Desierto de Altar in Mexico. Then look carefully beyond those peaks – you can see the faint outline of a distant ridge in the haze – those are much higher peaks across the Sea of Cortez which are in Baja California, as much as a hundred miles away in Mexico.

The Marines mark all their road junctions with posts like this one, which denotes the road heading east to the entrance of Spook Canyon. That is a fascinating place, and you can read about my excursion through it on this website by typing in the name “Spook Canyon” in the search bar at the top.

About 4 miles north of the turnoff for Spook Canyon, we come to a major junction. One sign says the Camino heads west, while the road we’ve been on bears a sign pointing north to Fortuna Mine. The maps, and history, seem to favor the route north, so we decided to head that way. The nature of the road changes dramatically here – instead of being a wide, level dirt road, it looks like this as we head north.

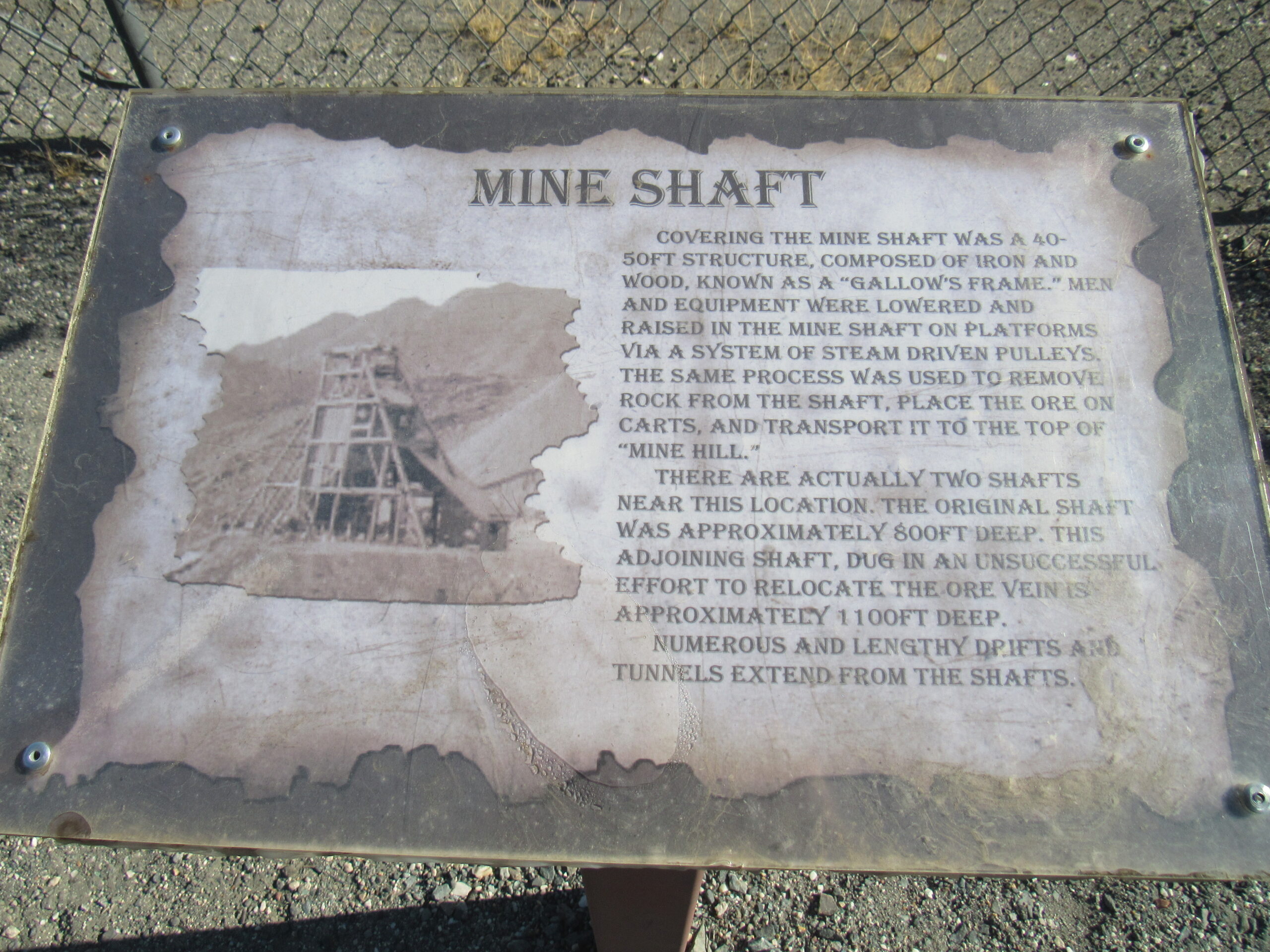

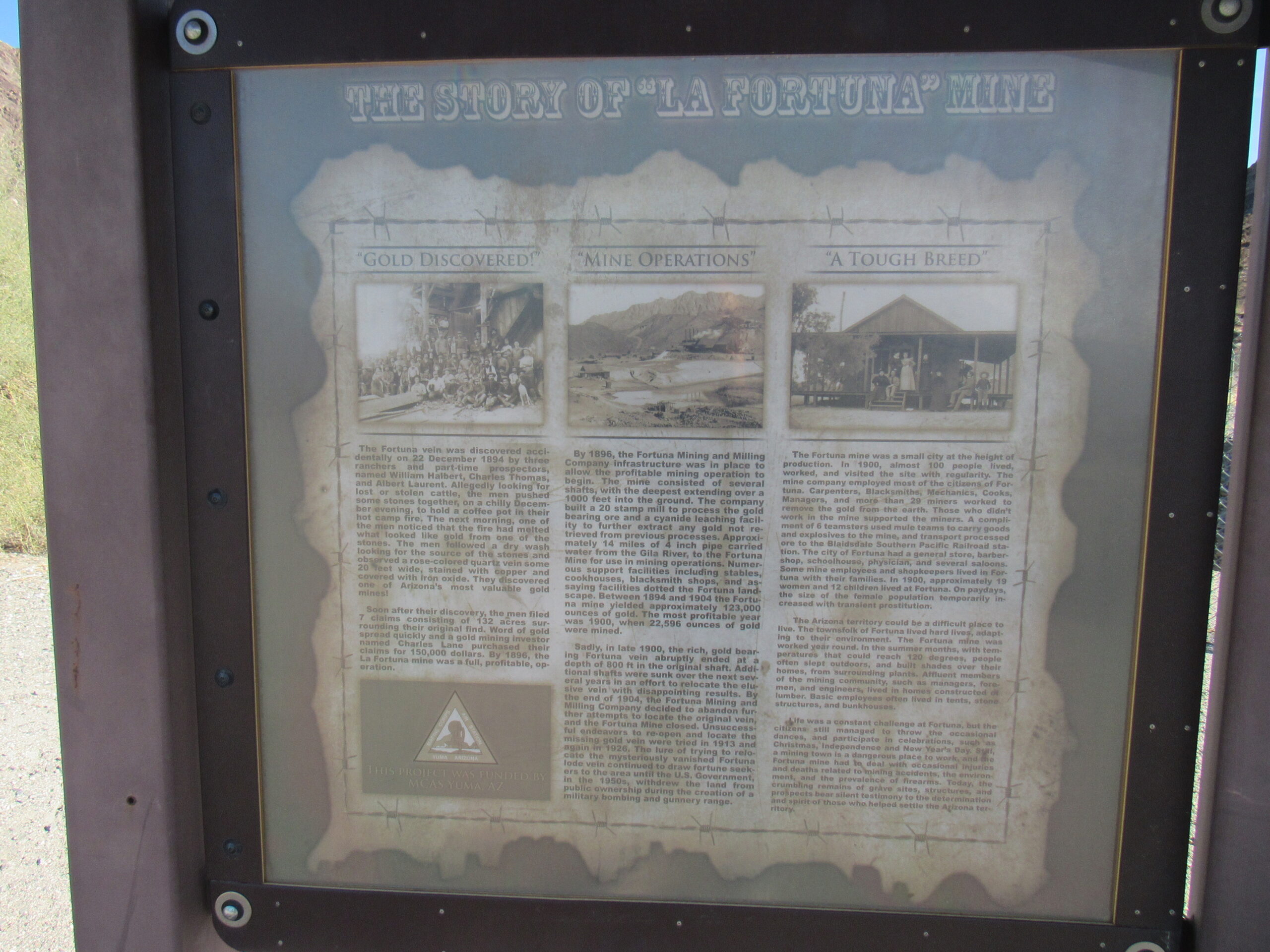

The road starts to climb and get rough – the sand is gone, and we enter the Gila Mountains. It twists and turns, following a wash in a canyon bottom. We see evidence of the old mine workings around us.

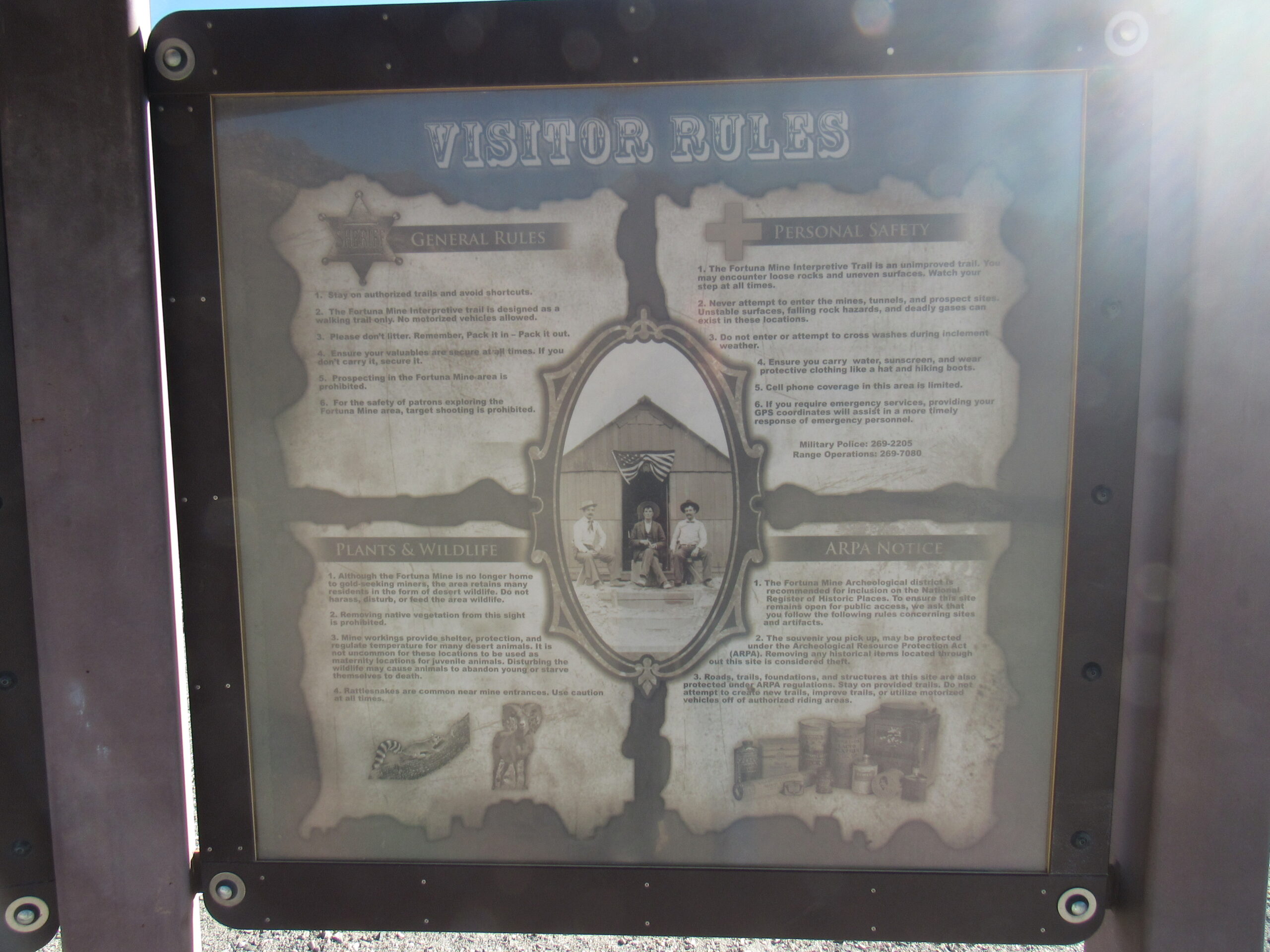

There are signs all over the place, each one telling things about the mine itself and about the life that the miners lived during the years the mine operated. It’s worth zooming in on each of these signs and reading about what went on here.

After driving around for a bit and exploring the mine area, we left it by continuing north into a more open area. Here is a picture I took almost 5 years earlier from a peak there – it plainly shows that we were still on the west side of the Gila Mountains.

We finally settled on a campsite down in a wash, to get out of the wind. I took this picture of my tent where I pitched it that evening. It is a North Face 2-person 4-season tent which I have used for over 30 years now. You see it here without the fly. It is a conestoga-style design, and it sheds wind and snow really well, having endured many bad storms and keeping me safe every time. It’s still in perfect condition after all that use – I love this tent!

Jake took this selfie of the 2 of us in camp that night.

We had another campfire that evening. Overnight, it only got down to 48 degrees, compared to the 28 degrees of the previous night.

We were close enough to the city of Yuma to easily see her lights that night.

That night, we could really hear the wind. It would build up speed and come roaring over the nearby ridge, sounding like a jet aircraft approaching. We left camp by 7:30 the next morning, and barely 30 minutes later, we drove off of the Barry M. Goldwater Range and entered the suburbs of the city of Yuma, Arizona. We had done it, the full 130 miles along the Camino del Diablo. What a great trip it had been! Jake was most enjoyable company, and traveling in his truck was about as luxurious a way to do it as can be imagined. We’re already planning a return visit.