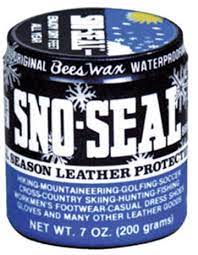

Boot Grease

When I started working in mining exploration back in the 1960s, we all wore leather work boots in the field. The boots were rugged enough, but something we had to do constantly was seal the leather. Leather boots back then weren’t waterproof, and since we were often traipsing through snow or water, we had to help the boots along by treating them. There was a product called Sno-Seal, and it was bees wax.

It worked best if the boots were dry and warm. You’d dip your fingers into the can and take out a dollop, then rub it into the leather. The leather would absorb the wax and give you a serviceable result. It was a nightly ritual, though, because it would wear off as you thrashed your way through the bush or through snow. At the end of each day, you’d dry your boots as thoroughly as possible, then apply the Sno-Seal. I used the stuff on my climbing boots until I finally left British Columbia in the early 80s. Nowadays, many boots are made with a Gore-Tex liner and don’t need such treatment.

Ostriches

The largest bird in the world alive today, ostriches are found only in Africa. They were introduced into Australia in the 1890s, but didn’t fare well. Again in the 1970s, ranchers tried to breed them but failed to do so successfully. Some escaped, others were released into the wild by ranchers who had given up. When I spent a month in Australia in 1992, one of the main reasons for my visit was so see as many of their birds as possible. In speaking with expert birders there, I was told that the chance of seeing an ostrich in the wild was near zero, so I didn’t try. A search of the internet in 2022 shows that once in a blue moon, one of these long-lived birds is spotted out there in the back country, living a solitary existence. Sadly, it’s only a matter of time before they all die off.

Summer Camp

In 1960, my family lived in Montreal. I don’t remember the whys and wherefores, but my parents decided to send me that summer to a Boy Scout camp. If they had to pay anything for it, it would have been a major sacrifice for them, as we were poor. That was the summer I turned 13. Away I went on the bus with the other scouts to someplace out in the forested countryside. I have no recollection where it was, but I do remember that it was a spot that was used by them every year.

I had never been away from home before and I became terribly homesick. The camp was to be for 2 weeks, and there were 2 boys to each small tent. Well, it rained almost every day, severely limiting what activities we could do. I decided that I hated the food that was prepared for us by the adults running the camp, but I think that was just an excuse to want to get out of there. Several of us boys decided that there was no way we were going to spend the entire 2 weeks out there, so we wrote letters home pleading with our parents to come and take us away from the hell on earth that we were barely surviving.

One week into the camp, they had a day where families could come and visit us. It turned out to be the first sunny day since we had arrived. My family showed up in an old car that my Dad had bought recently, the first car we ever owned. When I saw them, I burst into tears and pleaded with them to take me away from the gulag. It turned out that they had received my letter and were planning to take me home anyway. To this day, the things I most remember about the camp were the mosquitoes, the fireflies and the leeches that inhabited the stream by the camp where we would go for a swim.

Portuguese Television

I was traveling in South America and found myself in the town of Puerto Iguazú. It was a busy time because there was some sort of a big holiday and every hotel was completely booked up – not a room was to be found anywhere. When I realized this, I was standing outside the bus terminal in the middle of town – I must have looked especially perplexed. A cabbie pulled up and asked if I needed a ride somewhere, and I told him of my predicament. He said he knew a lady who lived in a nearby apartment building who sometimes rented a bedroom in her home and would I be interested in something like that. “Absolutely” was my response.

It was quite close by, and he walked me over to her place. She said that she’d be happy to let me occupy one of her 2 bedrooms. She was a single mother with 2 young daughters, about 6 and 8 years old. She quickly got the room ready for me, temporarily moving her daughters into her bedroom for my stay. It turned out just fine, I took my meals elsewhere and spent the days walking around the area seeing all the touristy things.

This town is in the area they call Tres Fronteras, because Paraguay, Brazil and Argentina all meet there. With just the rabbit ears on her television set, she could watch channels from Ciudad del Este in Paraguay, Puerto Iguazú in Argentina and Foz do Iguaçu in Brazil. I noticed that her girls watched a lot of programs from Brazil. The mother spoke no Portuguese and neither did I. She said her daughters had watched the Portuguese-language broadcasts from Brazil since they were babies – I guess those channels had the best programming. I asked her if they understood the Portuguese, and she said that they were completely fluent, having watched all that Brazilian television throughout all of their young lives. Of course, they also spoke Spanish as their native language. I thought that was pretty cool, learning a whole language by watching TV.

Long Days

The most brutal climbing trip I ever did was in the Granite Mountains. We arrived at the starting point, which happened to have a water supply. For 2 days, we climbed peaks out of that camp, but then it was time to move on. There would be no sources of water once we left that first camp, so we had to carry enough for 7 more days. It was soul-crushing. All that water, seven gallons, plus all of our camping and climbing gear, totaled 100 pounds each. We’d start in the dark each morning and plod north under the crushing weight. After a few miles, we’d stop, drop our packs and then climb something. As the day progressed, we’d continue north and then stop and climb another peak, doing anywhere from 2 to 4 peaks each day. It was always after sunset before we’d stop and camp for the night. By the time that stop came, we were physically exhausted and brain-dead. There was no pleasure in preparing an evening meal – we just wanted to forget the agony of the day and try to sleep. There was no alternative to this savage schedule because we had to finish climbing all of those peaks before our water ran out. Nearly all of them were unclimbed and foreign to us, so we had no information to go on – it was all exploratory. Every camp was a period of darkness, so different than the day’s climbing. We’d arrive after dark and leave the next morning in the pre-dawn darkness. Quite frankly, I don’t know how we did it. I was 66 years old at the time and, in retrospect, I’m surprised I didn’t have a heart attack.

Sea shell

It was October in the desert, still plenty hot. Late one afternoon I was climbing a small peak east of Chinaman Flat, and as I strolled up the easy slope, I saw something that shocked me. It was a sea shell, and it looked like one of these.

The internet says it is a scallop shell. Here’s why I was so surprised – the nearest place a scallop could live was in the Sea of Cortez, and that was 60 miles away as the crow flies. History tells us that Native American tribes in the desert southwest traveled long distances to trade goods with each other. I could only conclude that one such traveler had lost it there, probably long ago. It surprised me, though, so out-of-place.

Tafoni

There are rare places in the desert where these features can be found. The origin of the name is unclear, and many suggestions have been made as to how they are formed. Andy, Jake and I found these in the Sand Tank Mountains one hot summer day. You can Google them to learn more.

Rock Ring

In one of the remotest areas I’ve ever visited, I was climbing a small peak and happened to look down to the nearby desert floor. There, I saw 2 large rocks, each of which was surrounded by quite a few smaller rocks. Each of the smaller rocks was 6 to 12 inches across. Someone had taken the trouble to gather the small rocks from the surrounding desert floor and place them carefully around the large rocks. The only people to have been there before me were either undocumented persons coming up from Mexico, or Native American people. I think we can easily dismiss the indocumentados. They would have neither the time for nor interest in doing something like this. They would be moving as quickly as possible in order to not get caught by the authorities. Native peoples did build rock rings and sleeping circles as part of their culture but I don’t know if these qualify.

Packrats

Here in the desert lives a creature we call the packrat. I don’t know if they live in other places, but they are plentiful here. Humans regard them as pests, because they will do things like climb up into your vehicle’s engine compartment and chew on wires and cause a lot of damage. They are also called the white-throated woodrat, and their scientific name is Neotoma albigula. I don’t think there are many humans who are fond of these creatures.

In my desert wanderings, I often come across their nests (also called middens), which are pretty easy to spot. The real give-away is a big pile of vegetation, much of which is pieces of cholla cactus. The cactus parts serve to protect the nest and also as food. Here is a picture I took of such a nest. The small yellow things are pieces of a type of cactus we call the teddy-bear cholla. It’s amazing that they can handle those at all, as it is the most feared cactus that grows in our desert. If human tangles with one, it is a painful and memorable experience. The packrat is somehow able to move those pieces around and not suffer any consequences.

Cast-Offs

Each year, untold thousands of undocumented border-crossers try to sneak across from Mexico into the USA. They are from many different countries. Most are arrested, some turn back, quite a few die while trying to cross the desert. If you spend time out in remote areas like I do, you will come across their leavings. Occasional pieces are to be found everywhere, but once in a while I will come across a large amount of stuff left in one spot, like this pile my wife and I found in the Roskruge Mountains. There were more than 20 packs here. She had never seen anything like it before, and it scared her. Of course, the owners of this gear were long-gone, no doubt arrested by the Border Patrol. When arrested, they are only allowed to keep their personal I.D – all else must be left there.

The biggest pile of gear I ever saw, though, was in a lonely spot in the Sauceda Mountains. The personal effects left here made a pile 15 feet across, and included just about everything you could imagine carrying on a multi-day trip across the desert. Layers deep in places, this pile included: every type of clothing; all manner of foot-wear; blankets; sleeping bags; toiletries; water jugs; food packages; backpacks; stoves; fuel containers; cooking utensils. In this spot, I think what went on was that people were re-grouping, deciding what gear they could leave behind, taking only the bare necessities. They were all trying to reach Interstate 8, which was still 23 miles away. They still had to negotiate several canyons, a mountain pass, and miles of exposed country across an active military bombing range in order to reach “Ocho” where they would use a burner phone to call for a pick-up which would take them to a city where they could then disappear.